Donald Judd met Dan Flavin in 1962 at a gathering in a Brooklyn apartment organized to discuss the possibility of a cooperative artist-run gallery. They exhibited together a year later when their work was included in New Work: Part I at Richard Bellamy’s Green Gallery, New York (January 8–February 2, 1963). As their mutual friend, the artist John Wesley, has said of their friendship, “[the two] became Flavin and Judd for a while. The two names were together.”1

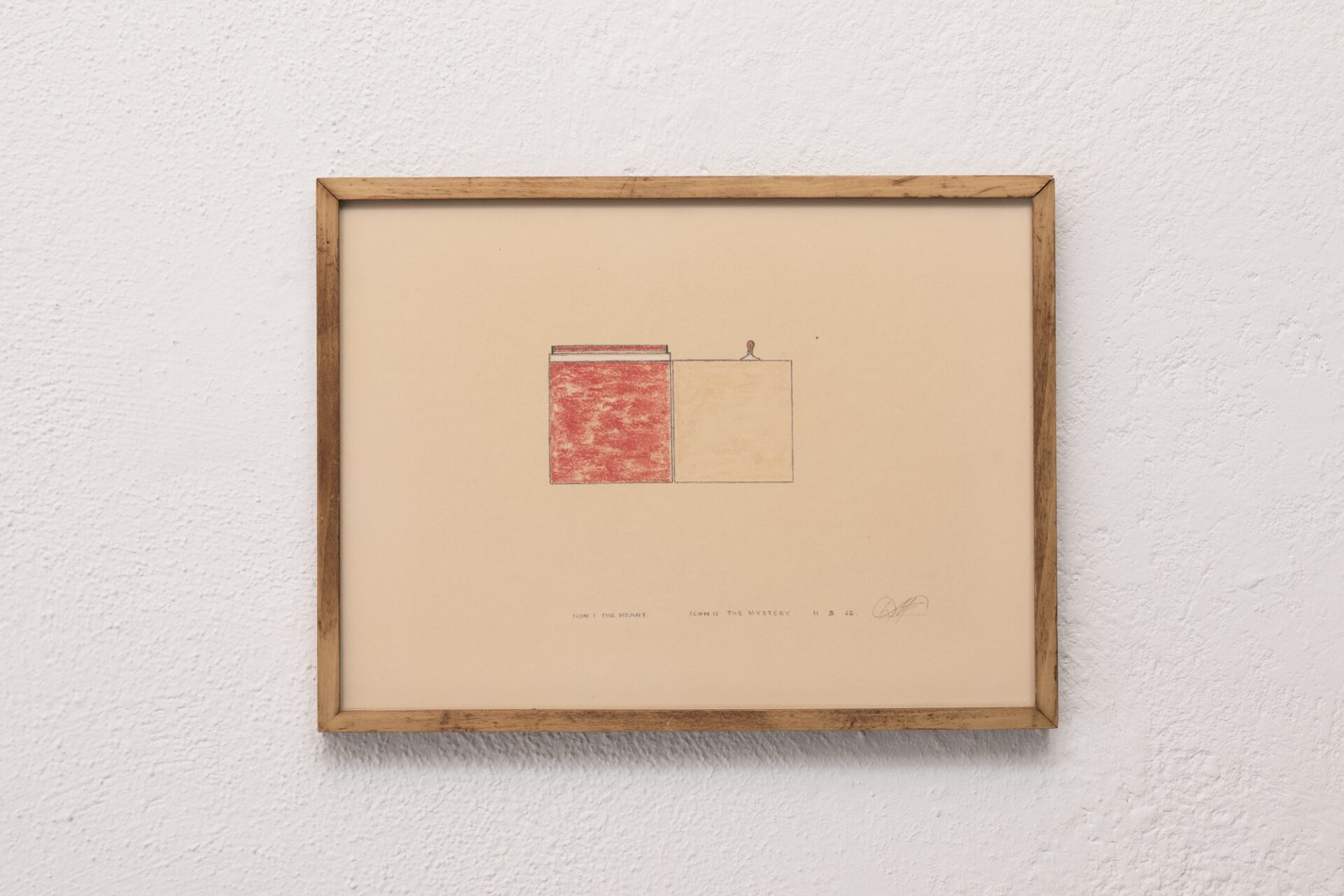

Flavin made many drawings for the icon series, of which eight variations were realized between 1961 and 1964. Judd installed two of these drawings on the fourth floor of 101 Spring Street (see ICON VI 1962–1963 (to Louis Sullivan)). In addition to the drawings, he also installed two icons on the fourth floor of 101 Spring Street (see icon III (blood) (the blood of a martyr), 1962, and icon VI (Ireland dying) (to Louis Sullivan),1962–63).

In this work, Flavin drew his first two icons side by side. In 1964, they were installed side by side in a horizontal row in his first solo exhibition, although not as closely together as they are in the drawing.

Flavin dedicated ICON I (THE HEART), 1961–62, to his friend Sean McGovern, “an Irish immigrant who worked with Flavin as a guard and elevator operator at the American Museum of Natural History in New York.”2 Before his employment as a guard at the American Museum of Natural History from May 1960 to October 1961, Flavin had worked as a guard and elevator operator at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, where he met Sol Lewitt, Robert Ryman, Robert Mangold, Sonja Severdija (later Sonja Flavin), and Lucy Lippard.

Flavin dedicated his second icon, ICON II (THE MYSTERY), 1961, to his friend John Reeves, “a teacher-editor and clairvoyant whom Flavin first met while attending Columbia University in New York.”3 In the late 1950s, Flavin attended the General Studies Program at Columbia for three semesters, where he sat in on lectures by the art historian Meyer Schapiro. Judd also studied with Schapiro during this time, as a graduate student in art history.

“While walking the floor as a guard in the American Museum of Natural History,” wrote Flavin, “I crammed my uniform pockets with notes for an electric light art. ‘Flavin, we don’t pay you to be an artist,’ warned the custodian in charge. I agreed, and quit him. . . . Then, for the next three years, I was off at work on a series of electric light ‘icons.’ (I used the word ‘icon’ as descriptive, not of a strictly religious object, but of one that is based on a hierarchical relationship of electric light over, under, against and with a square-faced structure full of paint light.)”4