In 1965, both Donald Judd and Barnett Newman were selected for the U.S. Pavilion at the Eighth São Paulo Bienal by the curator Walter Hopps. Newman, born in 1905, was roughly twenty years older than Judd and the five other artists selected by Hopps (Billy Al Bengston, Larry Bell, Robert Irwin, Larry Poons, and Frank Stella). While many contemporary critics were hostile to Newman’s work, he was viewed by Judd (as well as Dan Flavin and Frank Stella) as one of the most significant artists of the previous generation. As Judd had written the previous year, in his essay “Barnett Newman” (1964), “it’s not so rash to say that Newman is the best painter in this country.”

Judd’s first encounter with a significant number of Barnett Newman’s paintings was Barnett Newman: A Selection, 1946-1952, organized by Clement Greenberg at French and Company, Inc. in 1959. The exhibition included twenty-nine paintings and was the largest presentation of Newman’s work to that point. Meyer Schapiro, the influential art critic, historian, and professor, asked his Columbia University graduate students—including Judd—to view the exhibition. As Judd wrote, it was “a large and magnificent show of paintings.” Judd and Newman met for the first time when Newman fact-checked the essay, and the two became friends. As Judd recalled in a 1975 interview: “I met him [Newman] in ’64. I liked him a great deal; he was a good friend. He was a great painter and a smart man.”

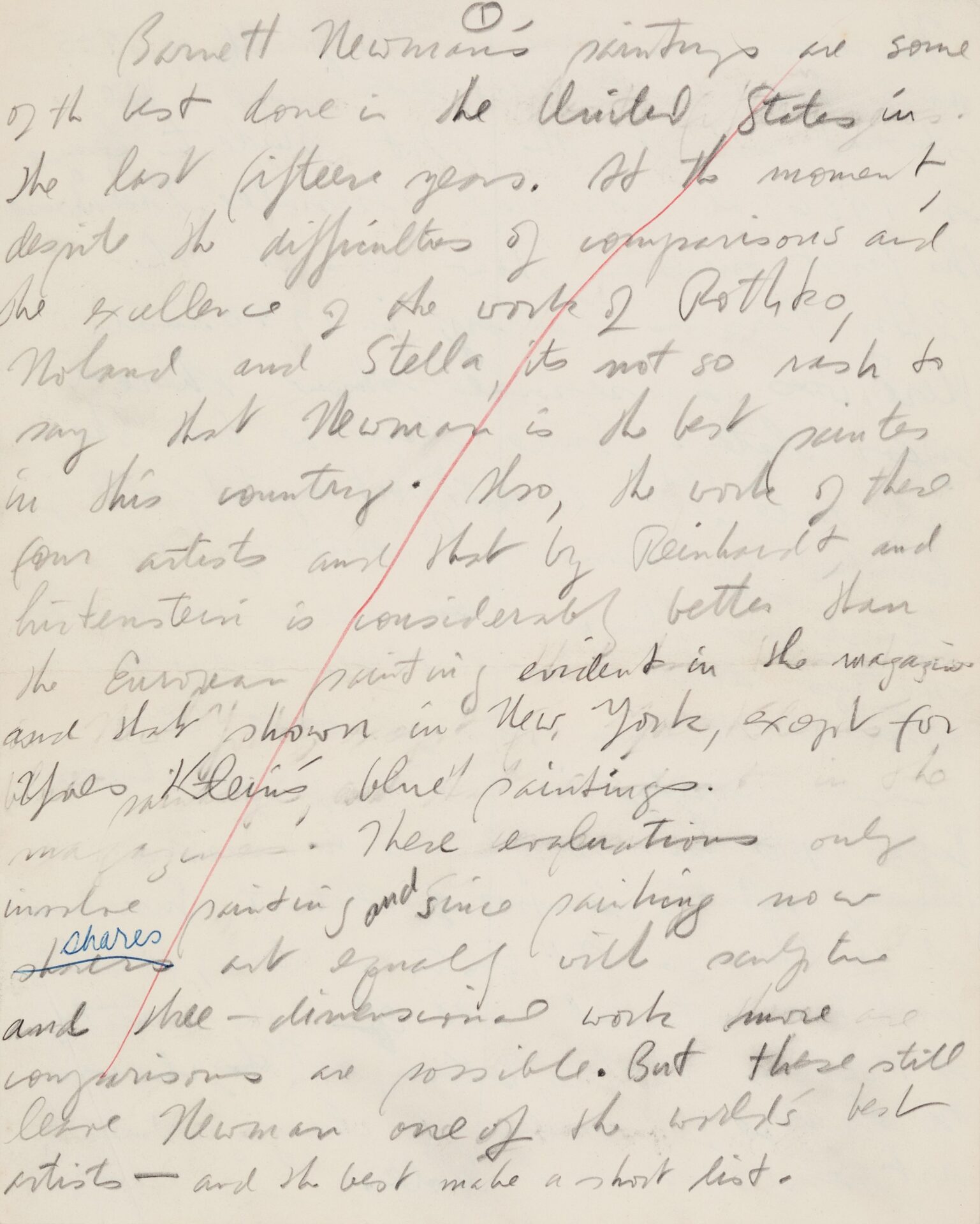

The essay “Barnett Newman” which Judd wrote for the German journal Das Kunstwerk, was not published in 1964 as planned, but was published by Studio International in February 1970. As Judd noted in a postscript, “Das Kunstwerk wanted this article in a hurry and never used it. Newman read it at the time.” In the opening sentence, Judd boldly asserted his opinion about the importance of Newman’s work, stating, “Barnett Newman’s paintings are some of the best done in the United States in the last fifteen years” (see below the first page of the handwritten and typed drafts). In addition to his assessment of Newman’s accomplishments, Judd described Newman’s work in ways that relate to concerns present in his own work, such as the importance of wholeness and rejection of composition and hierarchy:

The openness of Newman’s work is concomitant with chance and one person’s knowledge; the work doesn’t suggest a great scheme of knowledge; it doesn’t claim more than anyone can know; it doesn’t imply a social order. Newman is asserting his concerns and knowledge. He couldn’t do this without the openness, wholeness, and scale that he has developed. The color, areas, and stripes are not obscured or diluted by a hierarchy of composition and a range of associations. The few parts, all equally primary, comprise the quality of a painting.

Donald Judd, handwritten draft of “Barnett Newman,” 1964; Donald Judd, typed draft of “Barnett Newman,” 1964

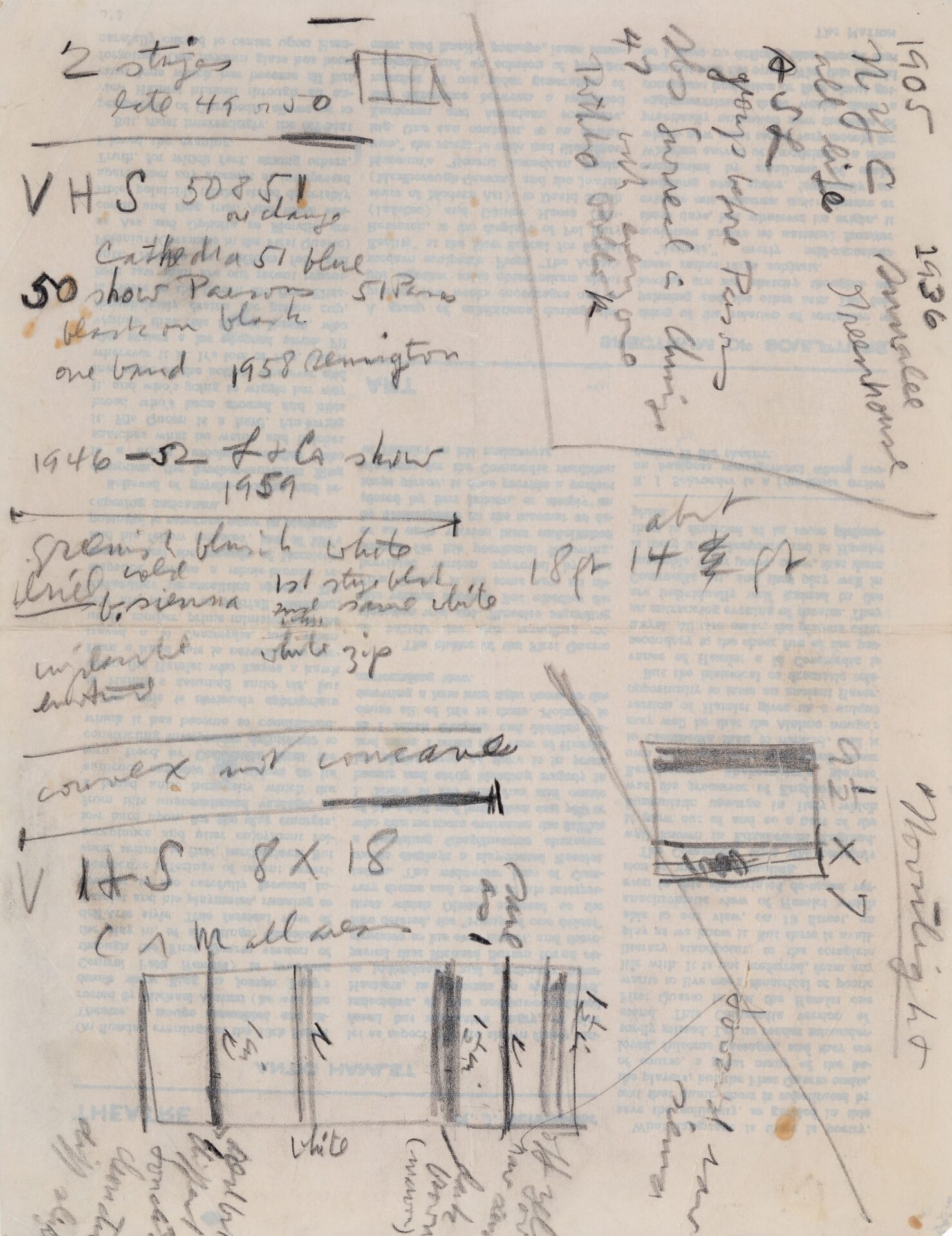

In the upper right-hand corner of an undated manuscript page, Judd notes facts about Newman’s life which he later included in the second paragraph of “Barnett Newman” (see below). These include the year of Newman’s birth (1905), that he lived in New York City all his life, and a list of group exhibitions in which his work was included. Additionally, Judd took notes on the dimensions and colors of some of Newman’s paintings and made small sketches of them. For Vir Heroicus Sublimis, referred to by Judd as “VHS”, he described the color of each of the painting’s vertical lines (“off yellow”; “toward raw sienna”; “dark brown”; “white”; “red but different”). In the essay, Judd wrote:

Newman’s color is itself a major and influential achievement. It is full, rich, and somewhat austere, for example, a lot of maroon and a little orange or a full blue and a whitened cerulean blue. Vir Heroicus Sublimis is a good example of the color.

Donald Judd, handwritten notes for “Barnett Newman,” 1964

Over time, Judd acquired three works by Newman, an untitled oil painting from 1949; 18 Cantos, an edition of eighteen lithographs from 1964; and Notes, a portfolio of seventeen aquatints and etchings from 1968. Judd installed Canto XVII, 1964 and Note II, 1968 in his Architecture Studio in Marfa, Texas.

In addition to shared artistic interests, Judd and Newman shared certain political perspectives. Both rejected top-down approaches to governance. Newman, for example, was an advocate of anarchist Peter Kropotkin’s and in 1969 helped to republish his Memoirs of a Revolutionist for which he wrote the foreword. Judd was an advisory member of Citizens for Local Democracy (CLD), “a non-partisan civic organization formed to promote the principle of local self-government and civic responsibility as the foundation of true responsible representative government.”

In 1969, Judd and Newman were committee members of Artists Against the Expressway, an organization chaired by Judd’s wife Julie Finch Judd (see Artists Against the Expressway letterhead below), that protested the Lower Manhattan Expressway, a controversial plan for an expressway through lower Manhattan which would have destroyed a large portion of the cast iron district in Soho. On June 7, 1969, Judd sent letters to artists, dealers, and critics, asking them to attend an Artists Against the Expressway meeting at the Whitney Museum of American Art on June 19, 1969 where Newman, and representatives from several community groups, spoke in opposition to the expressway.

Stationary for Artists Against the Expressway, 1969

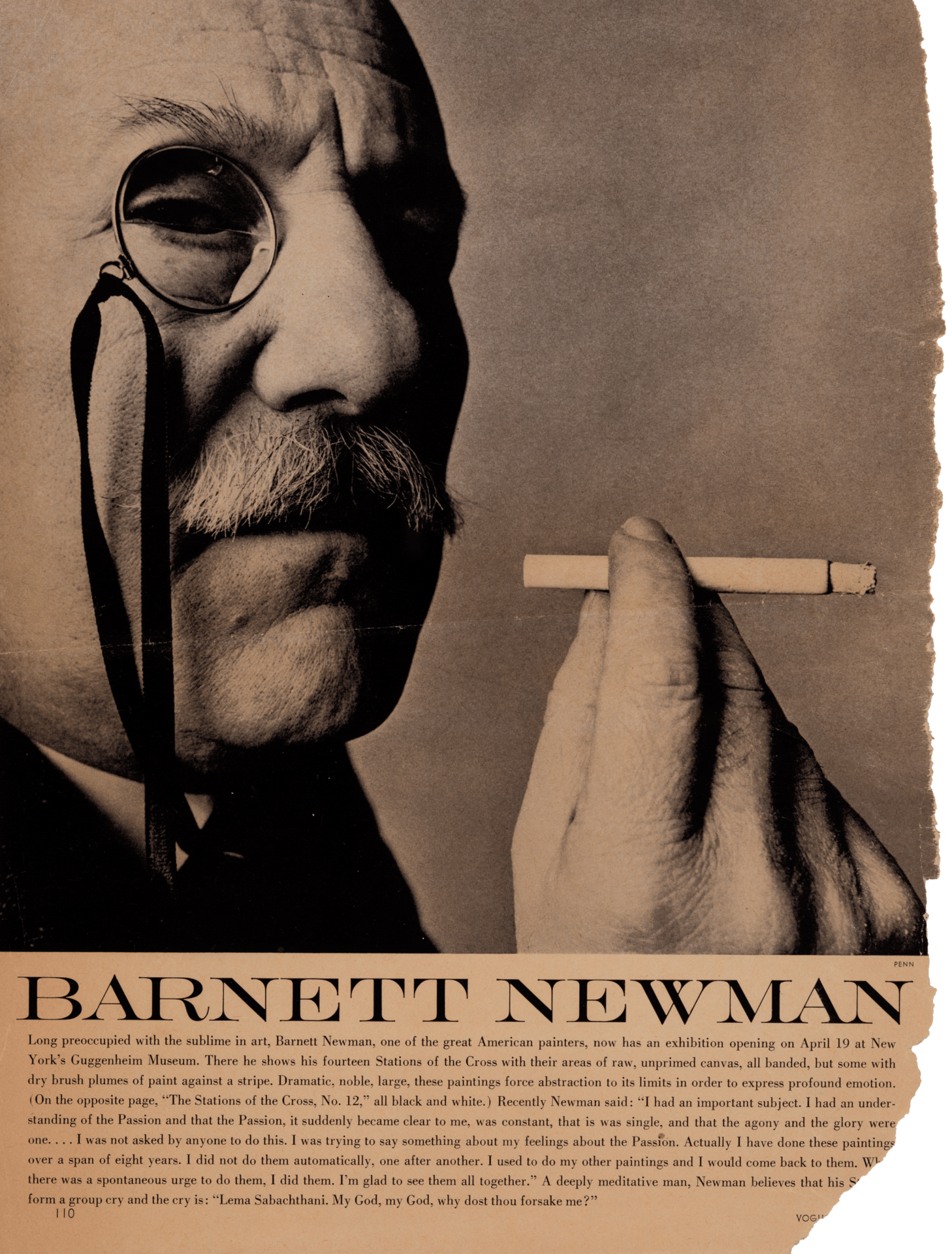

As was the case with many artists with whom he was friends, such as Yayoi Kusama and John Wesley, Judd kept selections of their exhibition announcements and clippings from significant press. Among his files on Newman there is a clipping from Vogue magazine’s April 1966 story “People Are Talking About…: Barnett Newman” which features a photograph of Newman taken by the renowned photographer Irving Penn.

Clipping from Vogue magazine, April 1966

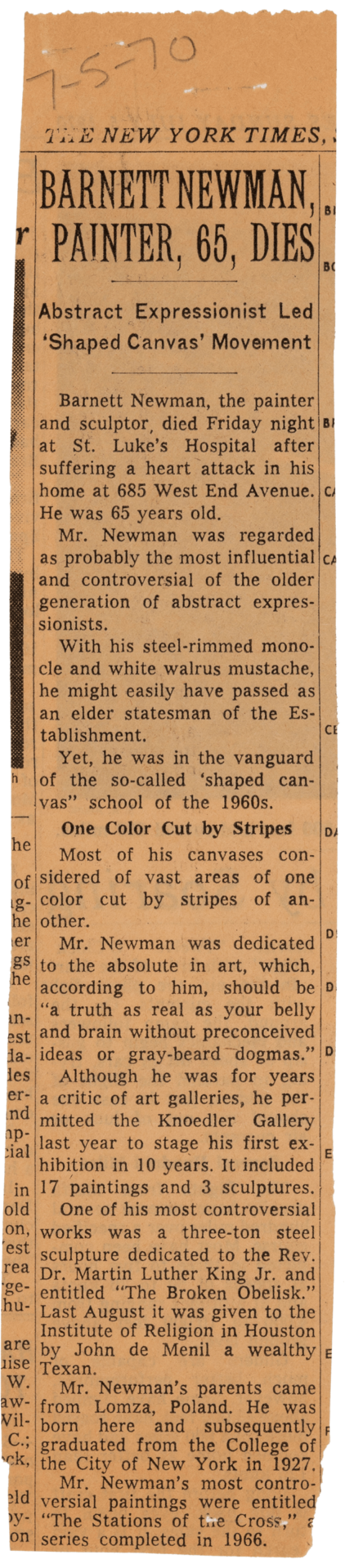

Reflecting on Newman’s death in the summer of 1970, Judd stated “I was very upset by his dying. He was the only one I knew of all those artists, the older artists.” In subsequent years, Annalee Newman, Newman’s wife, gifted several items to Judd, including two of Newman’s painting scaffolds, one of his painting palettes, a set of four chairs and a table, and a radio (see Newman’s obituary in the New York Times saved by Judd below). Judd installed these items in his Art Studio in Marfa, Texas.

Barnett Newman’s obituary in The New York Times, July 5, 1970. All archival items © Judd Foundation. Donald Judd Papers, Judd Foundation Archives, Marfa, Texas

Detail of Barnett Newman’s scaffolds at the Art Studio, Judd Foundation, Marfa, Texas. Photo © Elizabeth Felicella. Courtesy Judd Foundation.