In celebration of the 50th anniversary season of the Trisha Brown Dance Company, this Local History surveys Trisha Brown and Donald Judd’s collaborative endeavors for Son of Gone Fishin’ (1981) and Newark (Niweweorce) (1987). As Judd wrote, “Art and architecture—all the arts—do not have to exist in isolation, as they do now. This fault is very much a key to the present society. Architecture is nearly gone, but it, art, all the arts, in fact all parts of society, have to be rejoined, and joined more than they have ever been.”1

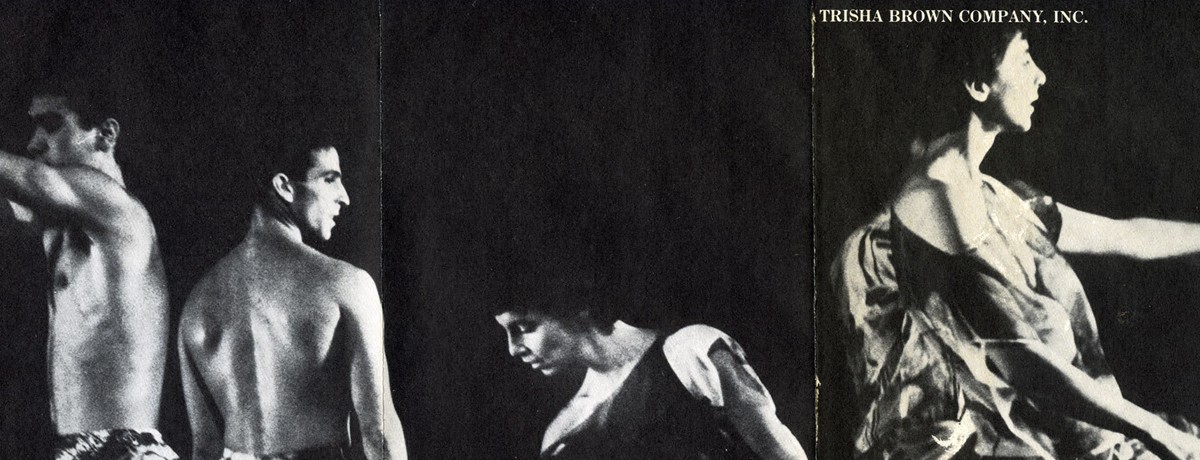

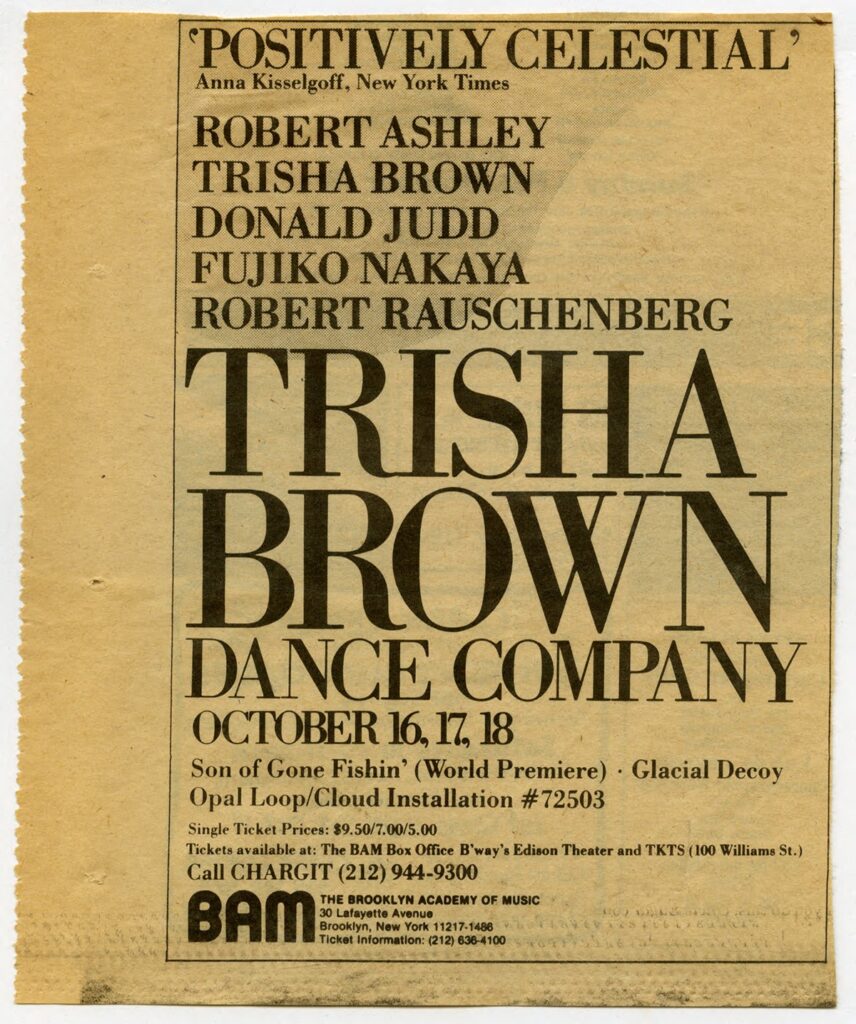

A telegram from Trisha Brown to Donald Judd dated October 15, 1981, the day before the opening of Son of Gone Fishin’ at the BAM Opera House in Brooklyn, New York, reads: “Set dance costumes music completed. We are in the theatre working. Company and I are thrilled.” Judd’s response to Brown: “Good luck. I hope my part is at least all right. Don.”

Born in Aberdeen, Washington in 1936, Trisha Brown’s formal training in modern dance began in 1954, when she enrolled at Mills College in California. As her choreography evolved, it formed into singular phases of work, each with similar compositional pursuits.“Add into this brew two summer sessions with Louis Horst, the formalist, at the American Dance Festival located at Connecticut College, and one with the improvisation wizard Anna Halprin located at Marin County, California, on an outdoor dance deck,” wrote Brown, “Here I encountered for the first time, the mercurial surges of intuitive process where physical proposals and responses were dished and dashed on a whiz-by playing field.”2

After graduating from Mills in 1958, Brown taught dance at Reed College in Portland Oregon before participating in a six-week workshop with Anna Halprin in the summer of 1960. Other participants in the workshop included Yvonne Rainer, Simone Forti and June Ekman. Moving to New York City in 1961, Brown joined Robert Dunn’s dance composition class at the Merce Cunningham studio. It was in Dunn’s class that Brown learned about John Cage’s chance procedures. Of this experience, Brown noted that she “understood for the first time, that the modern choreographer has the right to make up the WAY that he/she makes a dance.”3 As Steve Paxton, experimental dancer and choreographer wrote of Brown:

Trisha and her friends Simone Forti and Yvonne Rainer were some of the few dancers I knew in those days who improvised. The rest of us tended to create structures in which our rigid legs and pointy toes were accepted as the natural way for a dancer to exist…What were they doing? They were constructing milliseconds with their sensations and their ideas in a heady mix which swirled through time catalyzed by our complicity, our viewing. We saw anew. What a relief . . . Trisha Brown’s accomplishment is to express the new body, surmount the system, and beat the dictates of those who have no idea of their own body, or anyone’s.4

In 1970, Brown founded the Trisha Brown Dance Company with Carmen Beuchat, Caroline Goodden and Penelope [Newcomb].

The Company toured the United States and Europe performing works such as Accumulation (1971), a signature solo piece for Brown in which she, as scholar Susan Rosenberg describes, “unfolds increment by increment—from thumb to wrist, wrist to elbow, elbow to shoulder, shoulder to neck, hip to knee,” exposing “the cognitive challenge of performing, showing the dancer and the body in the course of thinking, not merely gesturing in space, and offers the satisfaction of watching a composition materialize according to an indissoluble unity of intent and action: the body’s vocabulary as a movement language.”5

Brown regularly performed outside of traditional theater venues, choosing instead to perform in lofts, galleries, and outdoor spaces, such as rooftops, parks, streets, churches, parking lots and plazas. When using conventional proscenium stages, Brown tried to disrupt the “window” or frame around the dancers and de-emphasize the customary hierarchical relationship of both the stage and the body, where the center is more important than the periphery.

Notable in Brown’s practice was her collaborative engagement with artists working outside of dance. As art historian and curator Hendel Teicher has described:

With the same collaborative spirit that marked her work from the moment of her arrival in New York in 1961, Brown embraced the theater as an interdisciplinary environment. Brown made dances that allowed, and even required, her dancers to talk; she unceremoniously broke the silence of the technicians of modern dance. Beginning in 1979, Brown’s creative sensibility for dialogue expanded in a new way to the visual arts when she invited Robert Rauschenberg to design the set and costumes for Glacial Decoy . . . Inviting Rauschenberg and, later, other painters, sculptors, and stage designers—Fujiko Nakaya, Donald Judd, Nancy Graves, Roland Aeschlimann, and Terry Winters—to join her in collaborative creation of a work for the stage became a central feature of her practice.6

In Son of Gone Fishin’ (1981) and Newark (Niweweorce) (1987), Brown, in collaboration with Judd, created works that decentralized the stage, developing allover compositions.

Son of Gone Fishin’ was part of Brown’s first fully developed cycle of work Unstable Molecular Structure. Of the choreography of this dance, Brown wrote:

The choreography was a ‘doosey.’ In it I reached the apogee of complexity in my work. The infrastructure of the piece was related to the cross-section of a tree trunk. ABC center CBA. Complex group-forms of six dancers were performed first in the normal direction and then in retrograde. Bob Ashley gave us a little library of different tapes to carry with us on tour. The dancers randomly chose which music we would use each performance. Something like having the band along with us.7

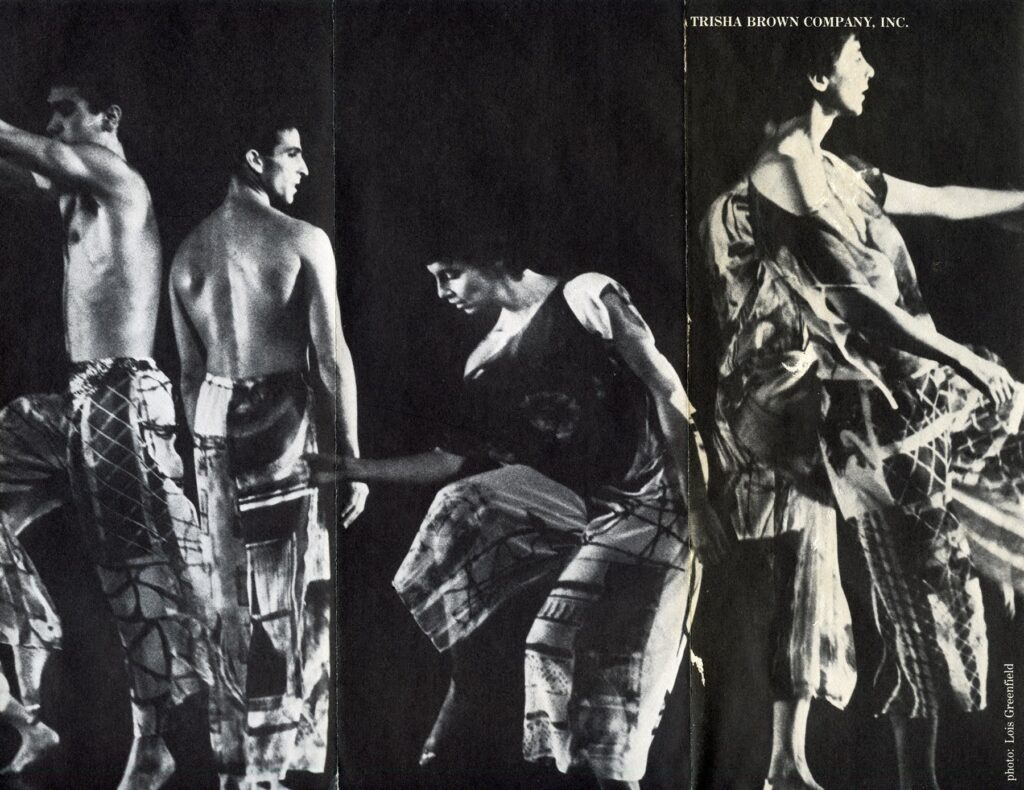

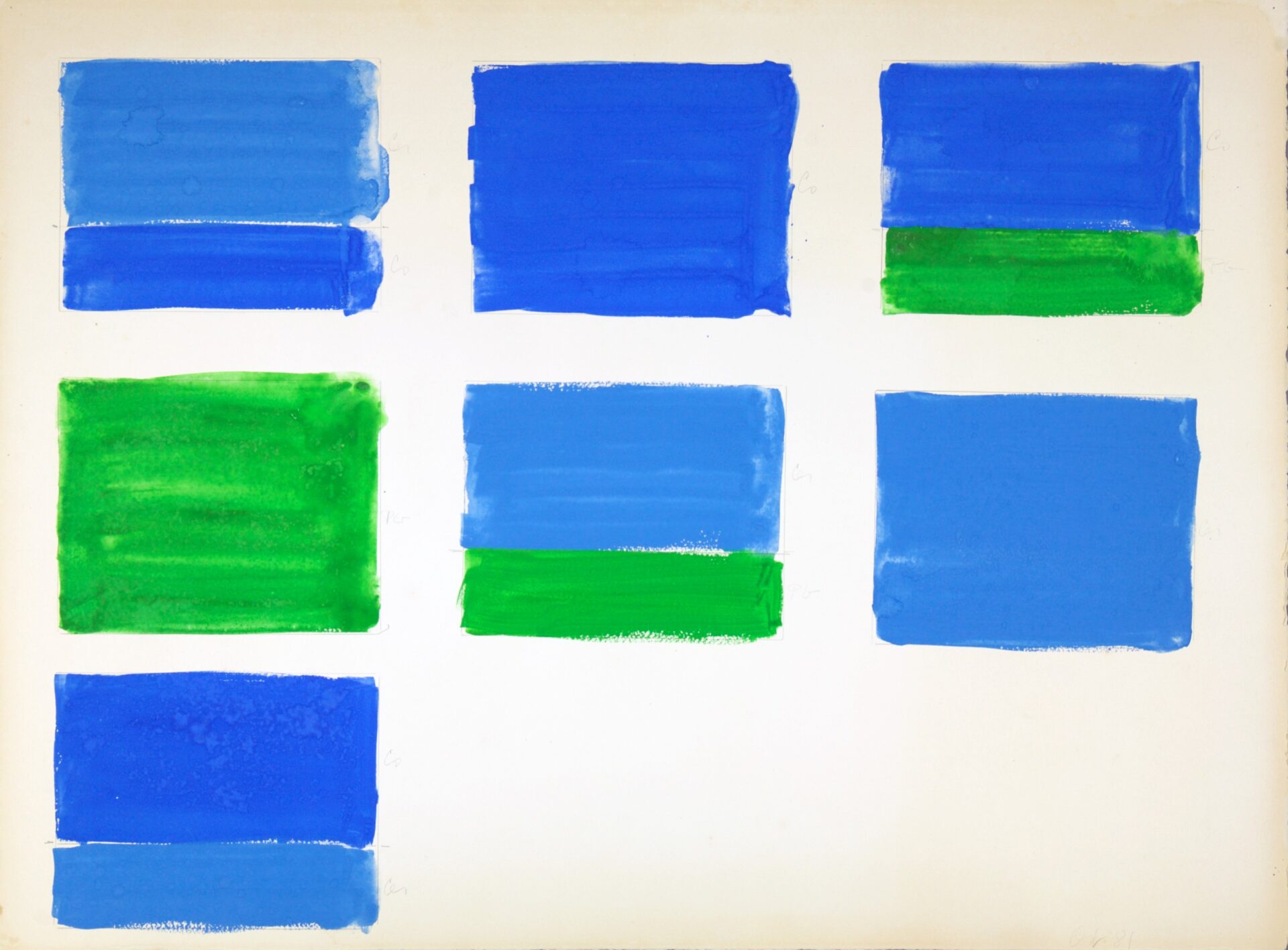

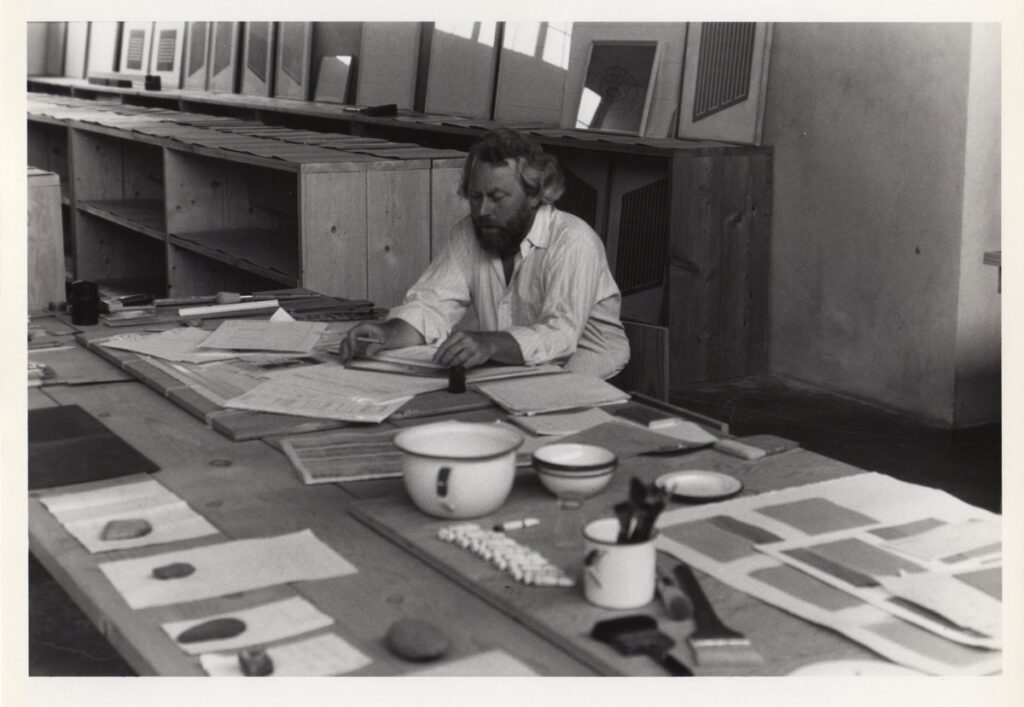

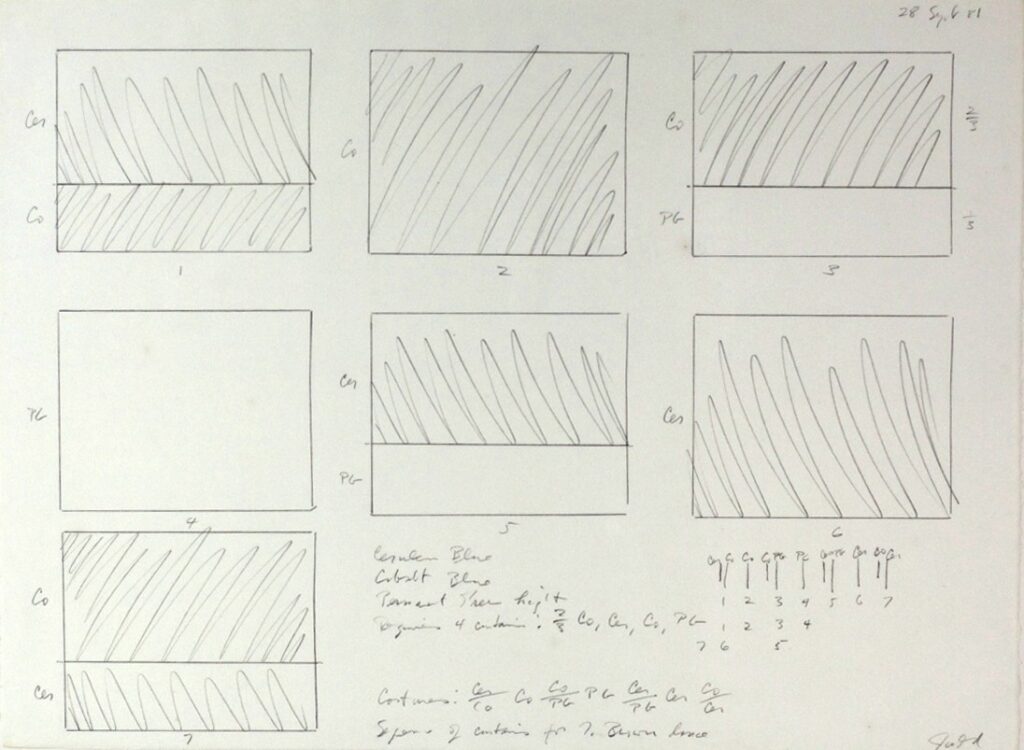

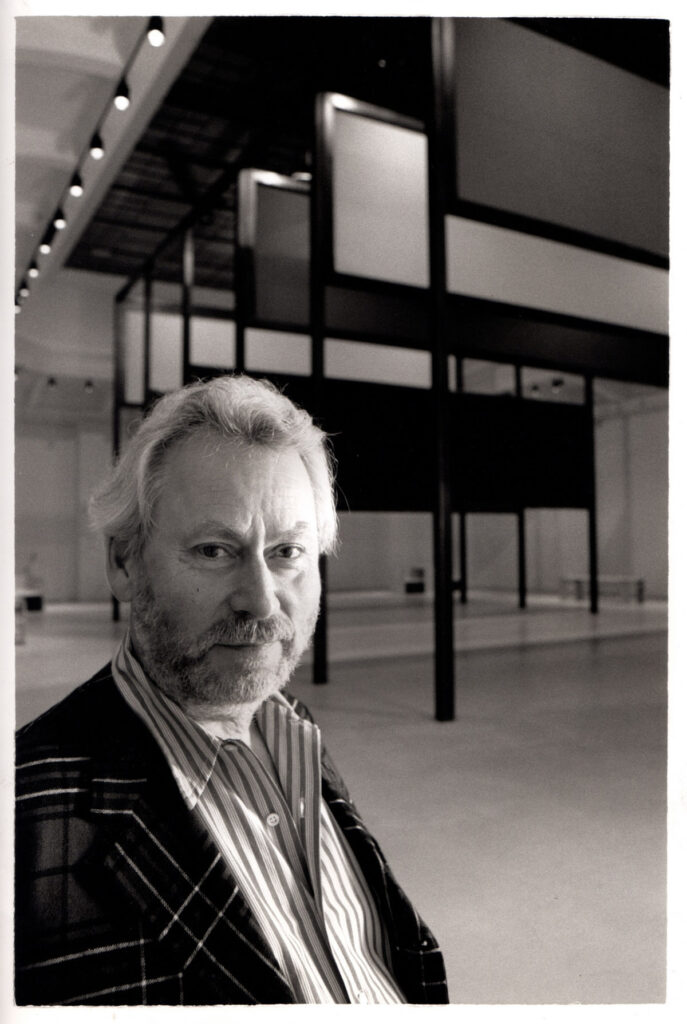

For Son of Gone Fishin’, his first collaboration with Brown, Judd developed the visual presentation and set. For the stage set, Judd created a series of five upstage drops that moved through a variety of positions. Judd created gouache on paper studies for these drops in cobalt blue, cerulean blue, and permanent green light (see below). Additionally, these studies can be seen in the bottom right of the photograph below of Judd in his studio at The Block/La Mansana de Chinati in Marfa, Texas.

Of the color of the drops in Judd’s set design, Rosenberg has noted:

These reflect Judd’s thinking about ‘color pairs,’…working with the three colored drops in Son of Gone Fishin’, Judd conceived of seven different compositions—corresponding to the seven units of Brown’s choreographic composition. Each drop appeared alone as a single color and in pairs where one drop was lowered to three-quarters of its full length, leaving four differently colored drops visible at the bottom quarter of the stage.

For Newark (Niweweorce), Judd contributed the visual presentation, sets, and costumes, while also providing the sound concept for Peter Zummo’s music and the direction for Ken Tabachnick’s lighting. The set design for Newark (Niweweorce) was a further development of the stage design Judd created for Son of Gone Fishin’. Judd created drops in cadmium red light, burnt sienna, cadmium yellow, deep blue, and cadmium red. As Brown described the relationship of the set on the choreography, “Drops rising and descending at different times, slightly alternating the amount of depth on the stage for the dancers. Hard edge.”8 Whereas the drops were used upstage in Son of Gone Fishin’, in Newark they use the entire stage. In January 2016, the Trisha Brown Dance Company restaged Newark (Niweweorce) at the Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM).

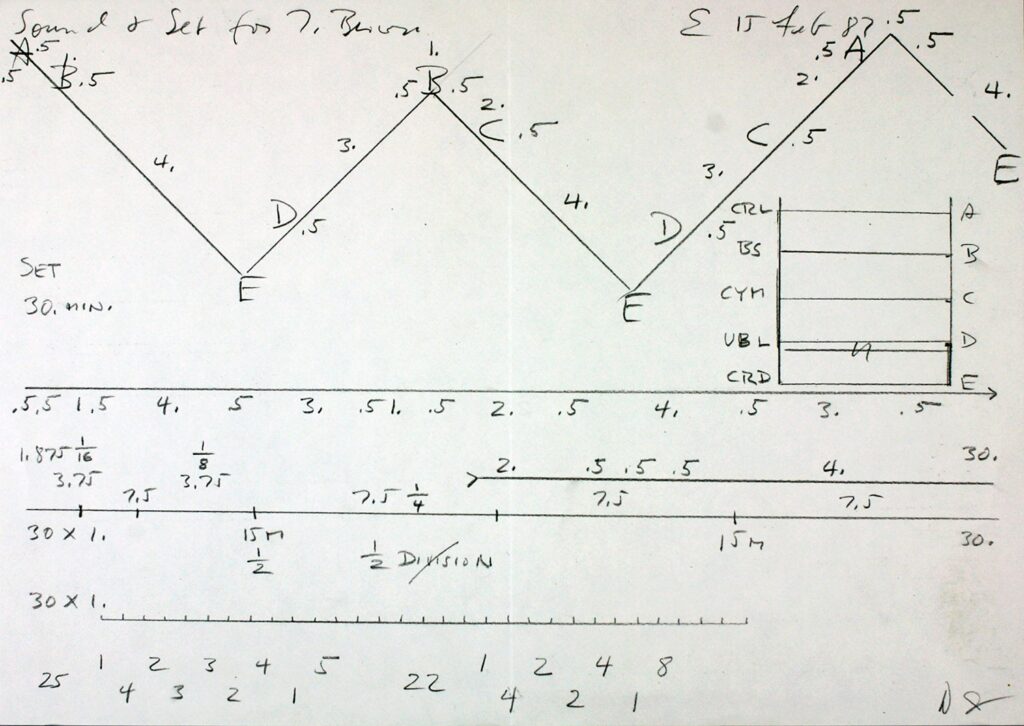

Judd’s thinking for the sequence of the drops and music can be seen across dozens of drawings. As Rosenberg describes, many of these drawings: “explored a single time scheme for the drops and sound, which included eleven total drop changes…With an abbreviated color scheme (A-E) he marked out timings and proportions on W-shaped diagrams—a format that the two artists [Brown and Judd] had used in their structuring of the relationship of sets to dancing in the earlier Son of Gone Fishin’.”9

“With the set I made,” Judd noted, “you would suddenly have a very shallow space for people on one side, and a very deep space with people on the other side, and all sorts of different circumstances—dancers would have to deal with that.”10

Judd’s sound concept, which was realized by Peter Zummo, called for bagpipe tones played by Judd’s good friend, the piper Joe Brady. Of the sound design, Judd stated in an interview from 1993:

What I needed were sounds – I just wanted sounds. I didn’t want them to be associated – I didn’t even want them to be from instruments, I didn’t want them to be natural; I just wanted a lot of sounds. And then a great range of volume, of density, of all the possibilities, and then I wanted to be able to cut it up into parts where you hear one, then one stops, and you hear the other with lots of subdivisions.11

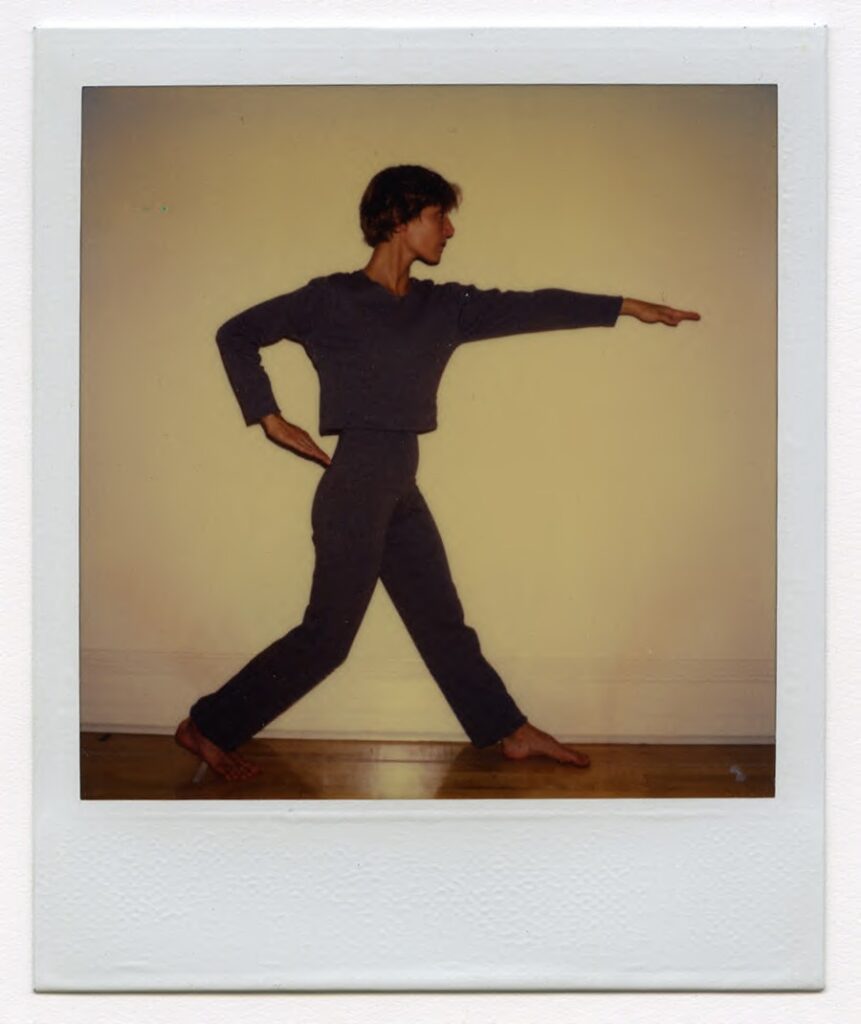

For the costumes Judd selected loose gray tops and bottoms (see polaroids below), which Brown augmented choosing gray unitards, which called “attention to precise lines and negative space internal to each body’s changing geometries.”12

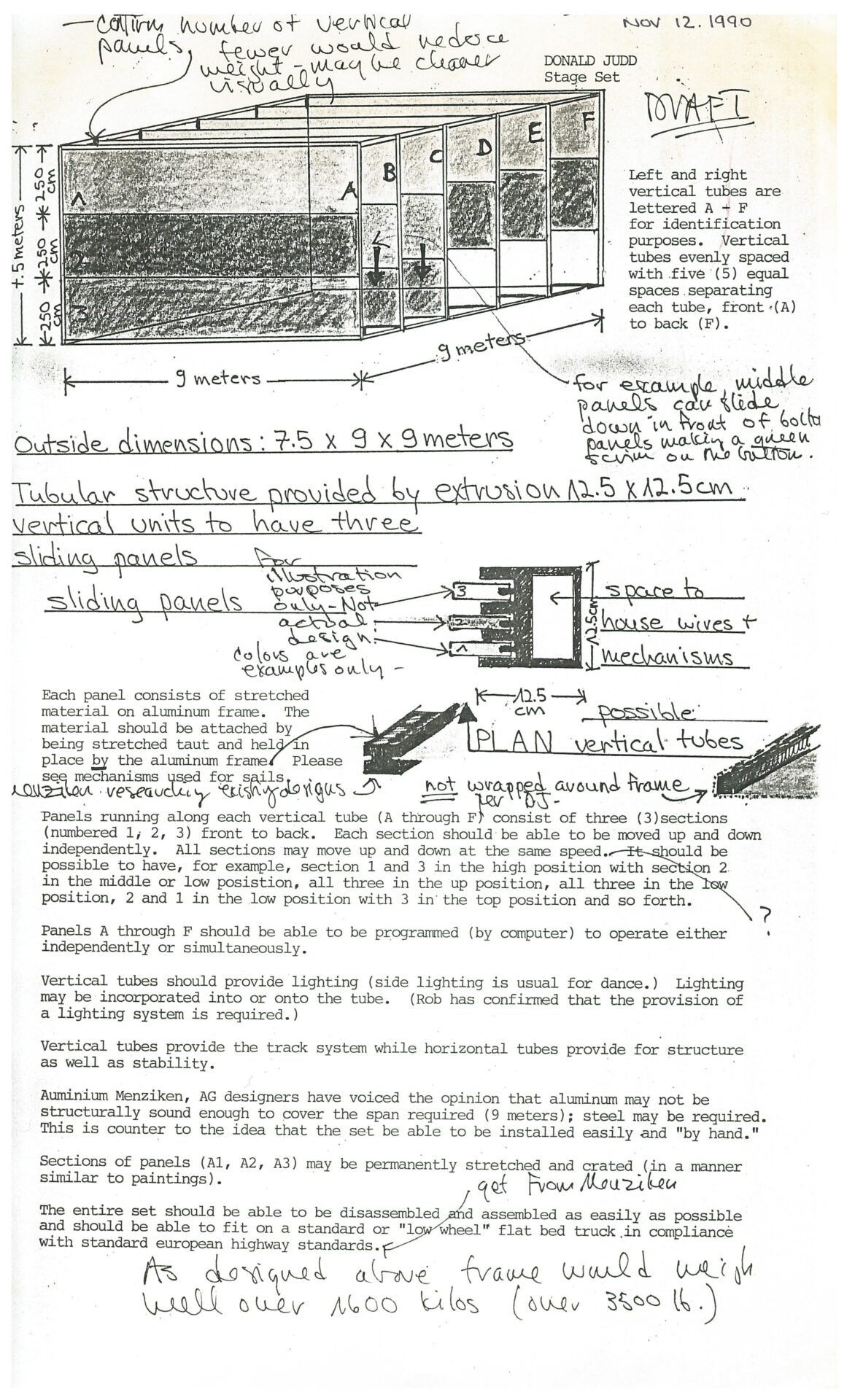

In 1990 Judd made a stage set with similar formal qualities to the set designed for Newark (Niweweorce) (see below the notes for the stage set dated November 12, 1990). Describing the purpose and construction of the stage set Judd stated:

The set in Vienna was made specifically for the exhibition and its steel welded together, so it doesn’t actually work. All the parts were originally meant to move up and down. And, of course, it should be made out of aluminum; it probably would have to have a special extruded frame. It would take quite a bit of mechanism. But it could be done; then it could travel all over – it could go on a tractor trailer and it could go all over the country.

First included in the exhibition Donald Judd: Architektur at the Österreichisches Museum für angewandte Kunst in Vienna, Austria (February 13–April 8, 1991), the stage set was gifted to the city of Vienna in 1995, and it has remained installed in Vienna’s Stadtpark since 1996 (see below Judd with the stage set in Donald Judd: Architektur and the stage set in Stadtpark).

In 2015, Judd Foundation hosted a series of performances at 101 Spring Street as part of the dance series, Trisha Brown: In Plain Site. The dance pieces were specially adapted for the floors of 101 Spring Street by Trisha Brown Dance Company’s Associate Artistic Director Carolyn Lucas and Diane Madden. Performances took place on all five floors of the building at timed intervals.

SON OF GONE FISHIN’ (1981)

CHOREOGRAPHY: Trisha Brown

CYCLE: Unstable Molecular Structure

LENGTH: 25 minutes

MUSIC: Robert Ashley, “Atalanta”

MUSIC PERFORMANCE: Robert Ashley with Kurt Munkacsi; live only at first performance

VISUAL PRESENTATION: Donald Judd

SETS: a series of five drops upstage, moving through a variety of positions by Donald Judd

COSTUMES: Judith Shea, based the final color scheme of the costumes on on Donald Judd’s green and blue set

LIGHTING: Beverly Emmons

ORIGINAL DANCERS: Eva Karczag, Lisa Kraus, Diane Madden, Stephen Petronio, Vicky Shick, Randy Warshaw

US PREMIERE:BAM Opera House, Brooklyn, NY, October 16, 1981

WORLD PREMIERE: Festival d’Automne à Paris, Théâtre de Paris, Paris, France, November 13, 1983

NEWARK (NIWEWEORCE) (1987)

CHOREOGRAPHY: Trisha Brown

CYLCLE: Valiant

LENGTH: 30 min

MUSIC: Peter Zummo, from sound concept by Donald Judd

VISUAL PRESENTATION: Donald Judd

SETS: Donald Judd

COSTUMES: Gray unitards by Donald Judd

LIGHTING: Ken Tabachnick with Judd’s directive to be “plotless”

ORIGINAL DANCERS: Jeffrey Axelrod, Lance Gries, Irene Hultman, Carolyn Lucas, Diane Madden, Lisa Schmidt, Shelley Senter

WORLD PREMIERE: CNDC/Nouveau Theatre d’Angers, Angers, France, June 10, 1987

US PREMIERE: City Center, New York, NY, September 14, 1987

This installment of Local History benefited from the scholarship of Susan Rosenberg, author of the volume Trisha Brown: Choreography as Visual Art. Rosenberg conducted research in the Judd Foundation Archives in 2014 and gave a lecture at 101 Spring Street in 2017 in conjunction with the exhibition Yayoi Kusama.

For more information about Trisha Brown Dance Company’s 50th Anniversary Season please visit the company’s website.

1 Donald Judd, “Statement for the Chinati Foundation/ La Fundación Chinati” (1986), in Donald Judd Writings, ed. Flavin Judd and Caitlin Murray (New York: Judd Foundation/David Zwirner Books, 2016), 486.

2 Trisha Brown, “How to Make a Modern Dance When the Sky’s the Limit” in Trisha Brown: Dance and Art in Dialogue 1961-2001 (MIT Press, 2002), 289.

3 Ibid., 290.

4 Steve Paxton, “”Brown in the New Body” in Trisha Brown: Dance and Art in Dialogue 1961-2001 (MIT Press, 2002), 289.

5 Susan Rosenberg, “Accumulated Vision: Trisha Brown and the Visual Arts,” Walker Reader, March 11, 2014, http://www.walkerart.org/magazine/2014/susan-rosenberg-trisha-brown.

6 Hendel Teicher, “Dance and Art in Dialogue: Introduction to Trisha Brown’s Choreography,” in Trisha Brown, 90.

7 Trisha Brown, “Part II Dance and Art in Dialogue 1979-2011,” in Trisha Brown, 114.

8 Trisha Brown, “Dance and Art in Dialogue 1979-2001”, Trisha Brown, 244.

9 Susan Rosenberg, Trisha Brown: Choreography as Visual Art (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2017), 298.

10 Donald Judd, “Interview with Regina Wyrwoll for the television documentary Bauhaus, Texas” (1993), in Donald Judd Interviews, ed. Flavin Judd and Caitlin Murray (New York: Judd Foundation/David Zwirner Books, 2019), 884.

11 Ibid., 882-83.

12 Susan Rosenberg, Trisha Brown: Choreography as Visual Art, 300-01.