“During the summer of 1968 we drove from Colorado through Arizona, Utah, and New Mexico. I was looking for a place, but one not much more than a campsite. The next summer we drove down the gulf coast of Baja California, which is excessively perfect in its lack of vegetation, inland at Bahía San Luis Gonzaga to the Pacific. The road was so wonderful that a day of driving eight hours resulted in eighty miles.”1

Jamie Dearing, Driving in Baja California, Mexico, 1971

Exploring areas of the Southwest that might be suitable for developing his large-scale work, Judd drove down from New York with his wife, Julie, and his son, Flavin in the summer of 1968. Finding Arizona too crowded and concerned that New Mexico would be too cold in the winter, he continued his search, traveling to the town of El Rosario in Baja California, Mexico where he would spend a month. Located off Highway 1 on the Pacific side of the peninsula, El Rosario is primarily an agricultural town, with a population only slightly smaller than the population of Marfa, Texas today (around 1,900 people). Although camping inland, Judd also spent time fishing off the coast at Fisherman’s Island.

Jamie Dearing, Fisherman’s Island, Baja California, Mexico, 1970

Recounting this first trip, Judd wrote:

“Having come across water, beer, and food we stayed a month in El Rosario with Anita and Heraclio Espinoza, whose place was famous as a base camp for botanists and paleontologists. Each of the two following summers we stayed a month in El Rosario and a month camped out fifty miles inland on Rancho El Metate, a Spanish grant to the Espinozas. The campsite was among palms on an arroyo with a pool near a very low mound, which had been the mission of San Juan de Dios de las Llagas, founded by Junípero Serra limping north to begin San Diego and Los Angeles.”2

James Dearing, Landscape, Baja California, Mexico, 1971

During his second and third trips to Baja in the summer of 1970 and 1971, Judd conceived of a site-specific project which responded to the slope of the canyon of Arroyo Grande, an area where two canyons descended from Cerro El Matomi. The site he selected was a valley nearby the canyon, which he described as having, “large cacti, all around, and blue palms along the arroyo…five or six miles up from the mouth of the canyon, which can almost be reached by a truck.”3

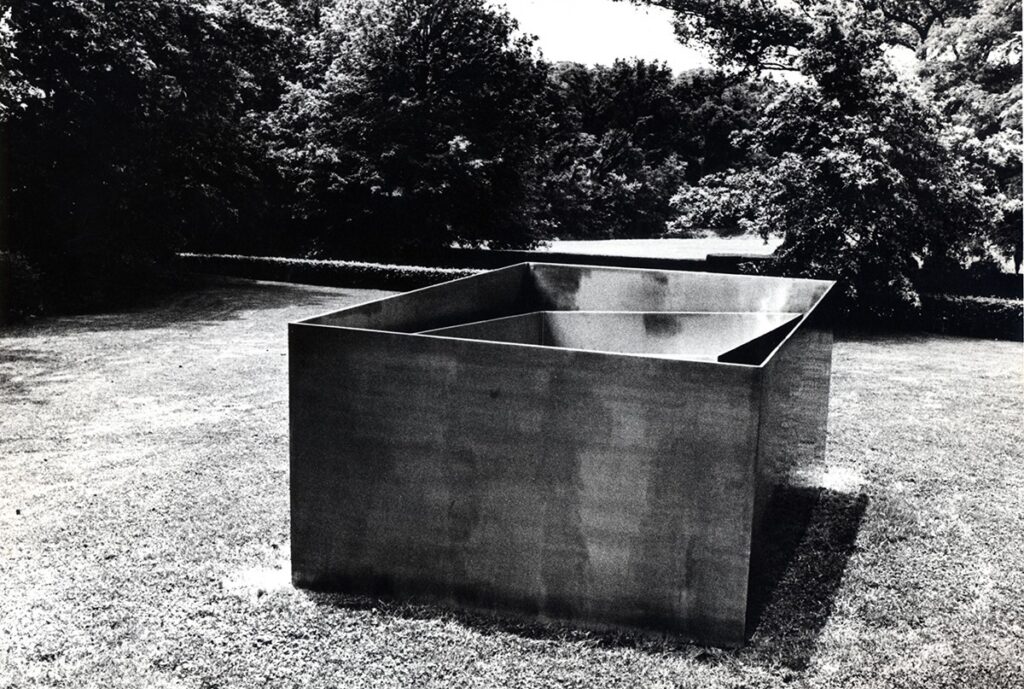

Donald Judd, untitled, 1971, stainless steel, 174 x 247.6 x 369.6 inches

This same year, Judd developed a site-specific piece for Joseph Pulitzer that also related to the terrain of the land. The work consists of two concentric walls of stainless steel, an inner and an outer wall. The outer rectangle is level and the inner rectangle follows the lie of the land. Judd described this as a “reasonable asymmetry” since it related to the specificities of the land itself. With this piece in mind, Judd designed his first single house for the valley of Arroyo Grande.

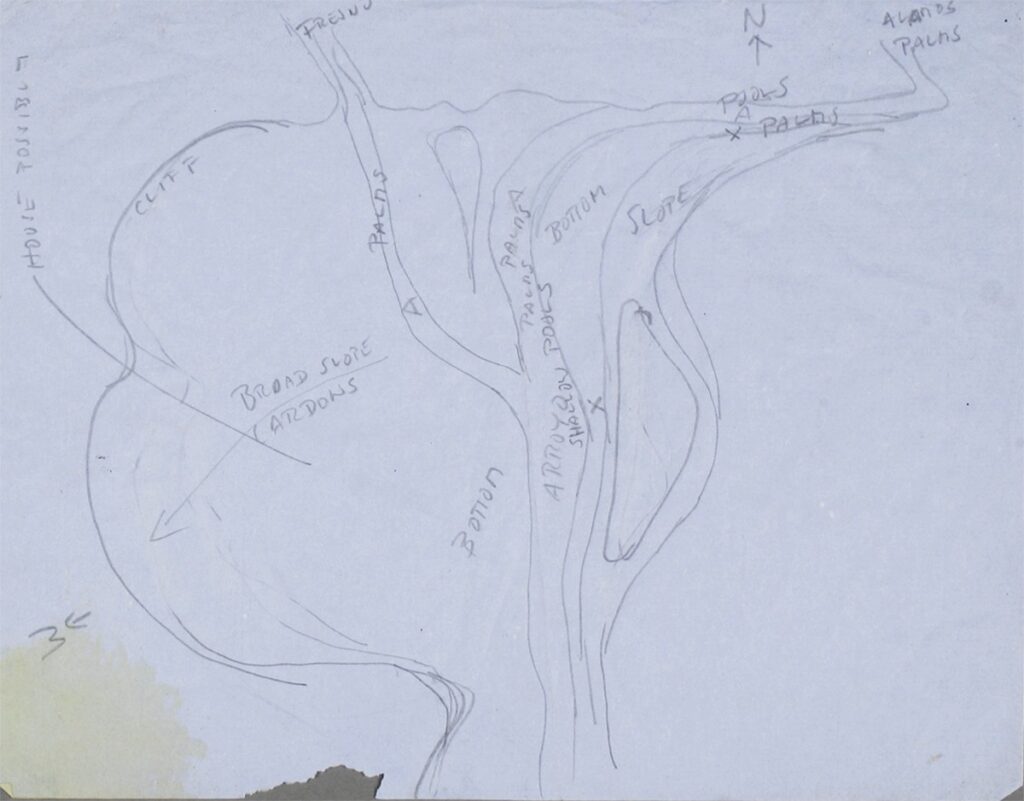

Donald Judd, map of Arroyo Grande, n.d., pencil on paper, 8 ¼ x 10 ½ inches

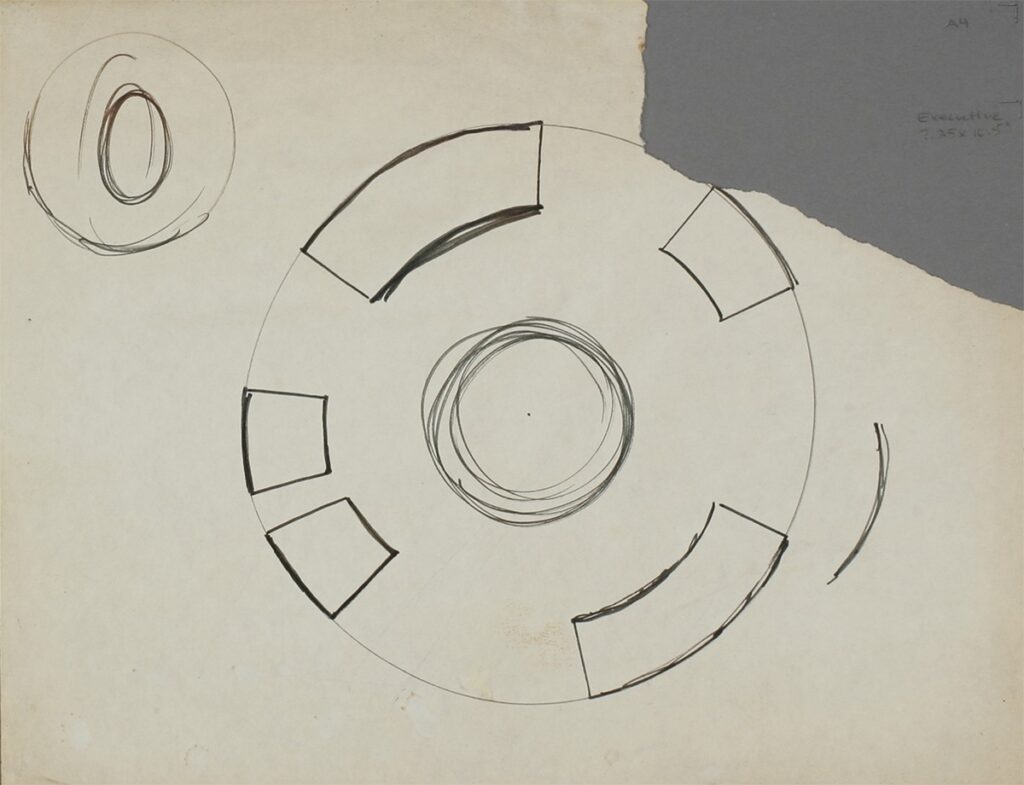

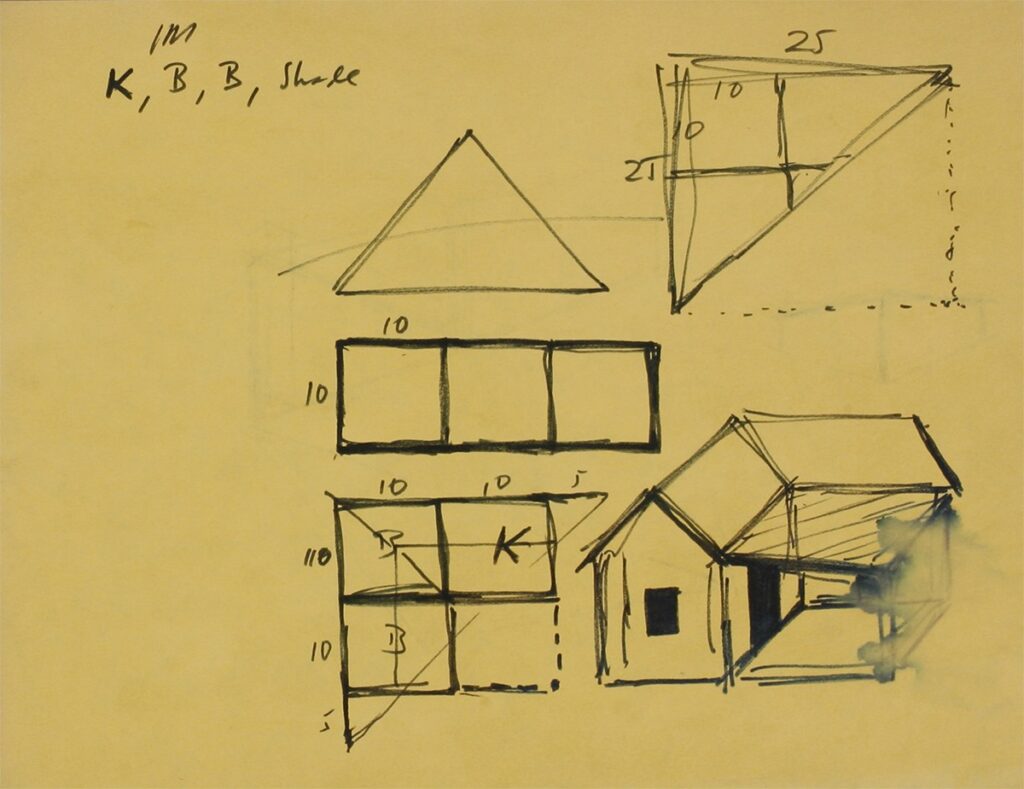

“A month of camping in the sun leads to the idea of a small house,” Judd wrote, “I made sketches of two possibilities for Arroyo Grande.” One of the two possibilities that Judd developed was for a round house to be situated around a pond, “whose bottom sloped into the slope of the land”, as he described. The circular house was to be discontinuous, divided into separate buildings. His second idea was for a triangular house that was to fit in the valley and was to have had concentric adobe walls,” noting later that this idea, “was a precedent for the complex in West Texas. But once the idea of a house grew beyond a shelter to include some art, being in Mexico became impossible since it would be hard to get the work into the country and impossible to get it out again.”4

Donald Judd, drawing for circular house at Arroyo Grande, n.d., pencil on paper, 8 1/2 x 11 inches

Donald Judd, drawing for triangular house at Arroyo Grande, n.d., pencil on paper, 8 1/2 x 11 inches

Although constructed over ten years later, the relationship of the adobe walls at La Mansana de Chinati/The Block, with an exterior wall that is level and an interior wall that is parallel to the slope of the land, reflects the ideas that Judd was developing, but was unable to realize while in Baja.

Elizabeth Felicella, Exterior, La Mansana de Chinati/The Block.

1 Donald Judd, “Marfa, Texas,” 1985

2 Ibid

3 Donald Judd, “Arroyo Grande,” 1989

4 Donald Judd, “Marfa, Texas,” 1985