Donald Judd amassed an impressive resume of writing as a for-hire art critic, often reviewing over fifteen shows a month during a six-year period from 1959 to1964. Although this period of Judd’s writing is notable for the categorical utterances housed within brief reviews that occasionally ran no more than five sentences long, it is also during this period that his penchant for the essay emerges in longer-form writings such as, “New York City: A World Art Center” (1962), “Local History” (1964), and “Specific Objects” (1964).

Judd’s “Specific Objects” became an canonical text for the 1960s and was all the more seminal because it was written not by a critic or an art historian, but by an artist. “In 1966, Judd was a topic of endless conversations among the artists I knew,” Mel Bochner wrote, adding, “His writing and his sculpture influenced us all. We admired his cool demeanor, rigorous intelligence, polemical toughness, and uncompromising belief in the importance of art.” After quitting his job as an art critic in 1965, Judd continued to channel these qualities into his writings. Counter to the restrictions inherent in writing monthly reviews (although he pushed these boundaries also) Judd’s essays are longer expositions that often have clear polemical intentions.

In his 1972 book Peinture et réalité, philosopher Étienne Gilson wrote, “Being a painter doesn’t prevent the artist from also being a writer, but he won’t be able to practice both at the same time. Real painters are well aware that they must choose between painting, writing, and speaking.”[1] For Judd, an artist who maintained an avid writing practice throughout his life, Gilson’s assessment is restrictive. In his essays “Complaints: Part I” (1969) and “Complaints: Part II” (1973), Judd uses writing as an opportunity to address what he viewed as failures in art criticism and museums, respectively. It’s interesting to quote from the first few sentences of each “complaint”:

From “Complaints: Part I” (1969): “I haven’t written anything in quite a while; I have a lot of complaints. Most of these are about attempts to close the fairly open situation of contemporary art. There are a lot of arguments for closure: a whole aesthetic or style, a half aesthetic or movement, a way of working, history or development, seniority, juniority, money and galleries, sociology, politics, nationalism. Most discussion of these aspects is absolute; something is the only true art and something else has got to go. Usually little is said about particular works and artists and nothing about the actual differences and similarities between artists.”

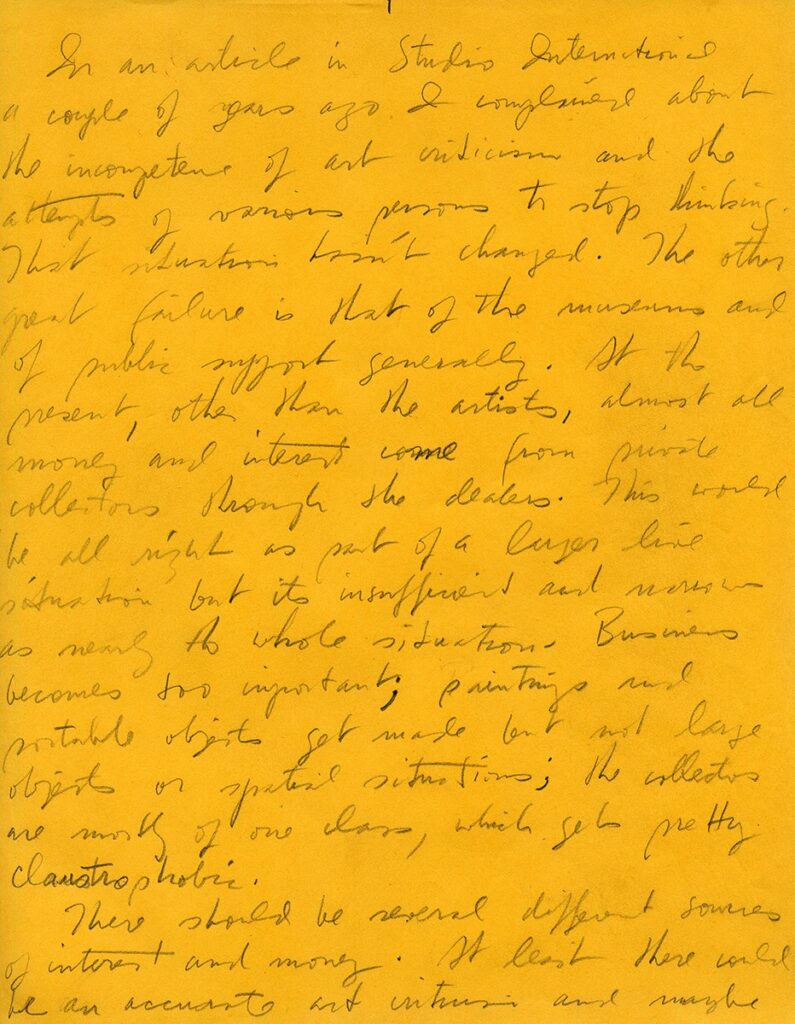

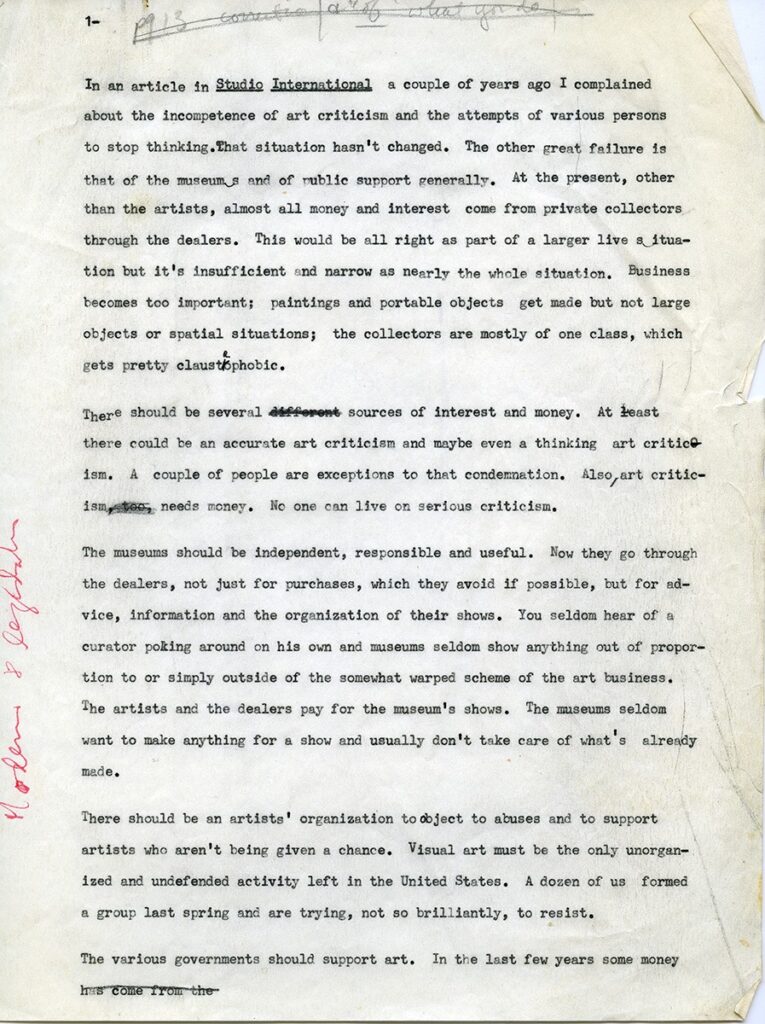

From “Complaints: Part II” (1973): “In an article in Studio International (“Complaints: Part I”) a couple of years ago I complained about the incompetence of art criticism and the attempts of various persons to stop thinking. That situation hasn’t changed. The other great failure is that of the museums and of public support generally. At the present, other than the artists, almost all money and interest come from private collectors through the dealers. This would be all right as part of a large live situation but it’s insufficient and narrow as nearly the whole situation.”

In these instances, Judd is using the essay form as an opportunity to criticize, but also to correct. These are not complaints solely, but recommendations. In four of the first five paragraphs of “Complaints: Part II,” Judd uses the verb “should” in the first sentence of each paragraph:

“There should be several sources of interest and money.”

“The museums should be independent, responsible, and useful.”

“There should be an artists’ organization to object to abuses and to support artists who aren’t being given a chance.”

“The various governments should support art.”

The “should” of Judd’s essays, returning again to Bochner, demonstrates his “polemical toughness, and uncompromising belief in the importance of art.” “Should” appears throughout Judd’s essays. It is found in “Imperialism, Regionalism, and Nationalism” (1975) (“Most of the present beliefs should be dead beliefs…); in “On Installation” (1982) (“The artist should be paid for a public exhibition as everyone is for a public activity”); and later in “Cacalomilli” from 1992: “A lot more should be written.”

From this perspective, it might be more apt to describe Judd’s work not in terms the essay as a noun, but instead to essay, as a verb meaning attempt or try. Disinterested in merely describing how things are (in art or in politics), Judd instead focuses on how things should and shouldn’t be. It is in his essays that one finds Judd’s sustained attempts to change not only practical issues in the art world, but the fundamentals of how we conceive of, make, and experience art.

Donald Judd Writings, first published by Judd Foundation and David Zwirner Books in 2016, is available as of February 2018 in its second printing. The publication comprises the most comprehensive collection of Judd’s writing including, unpublished college essays, and hundreds of previously unpublished notes, a critical part of his writing practice. Donald Judd: Complete Writings 1959-1975, first published on the occasion of Judd’s 1975 retrospective at the National Gallery of Canada, contains his art criticism and early essays and was published by Judd Foundation in its reprint edition in 2015.

[1] Étienne Gilson’s The Philosophy of St. Aquinas (New York: Dorset, 1986) can be found in Donald Judd’s library in Marfa, Texas.