In his 1990 essay “Una stanza per Panza,” Donald Judd recounts his dealings with the Italian art collector Giuseppe Panza, detailing Panza’s fabrication of his work without his permission and in some instances, without his knowledge. This essay was the result of a two-decade long relationship that turned acrimonious in the early 1980s after repeated attempts by Judd to correct wrong and unsupervised fabrications and to prevent further forgeries of his work by Panza.

As Judd recollected in “Una stanza,” “I wrote Panza” making clear that “Work made without my supervision is not my work. You cannot continue to do so.” In the essay Judd describes his multiple meetings with Panza; he recalls conversations with leading museum directors; and he quotes heavily from Panza’s own public statements in catalogues and magazines. This documentation, what Judd referred to as his “Panzata,” is included in the Museum, Gallery, and Collector files of the Donald Judd Papers part of the Judd Foundation Archives. These records document Judd’s extensive exhibition history and his relationships with curators and collectors.

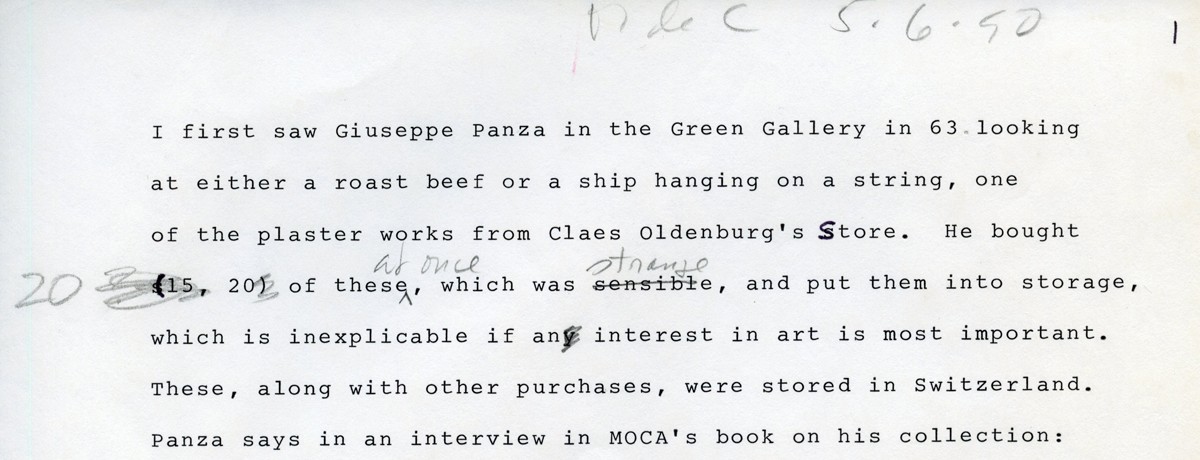

“Una stanza per Panza,” Judd’s longest essay at more than 25,000 words, was first published in 1990 in four parts in German and as an English language supplement by Kunst Intern of Bonn, Germany.

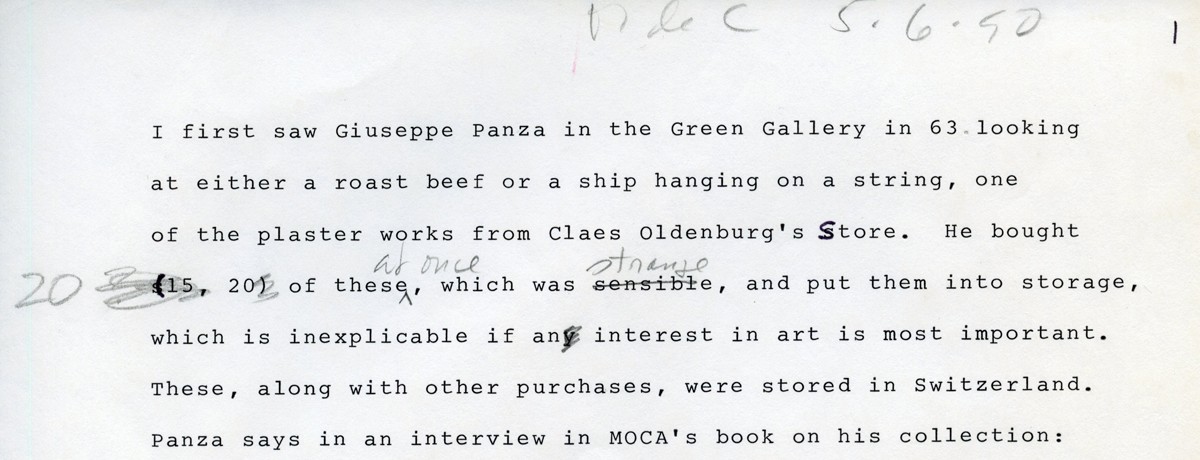

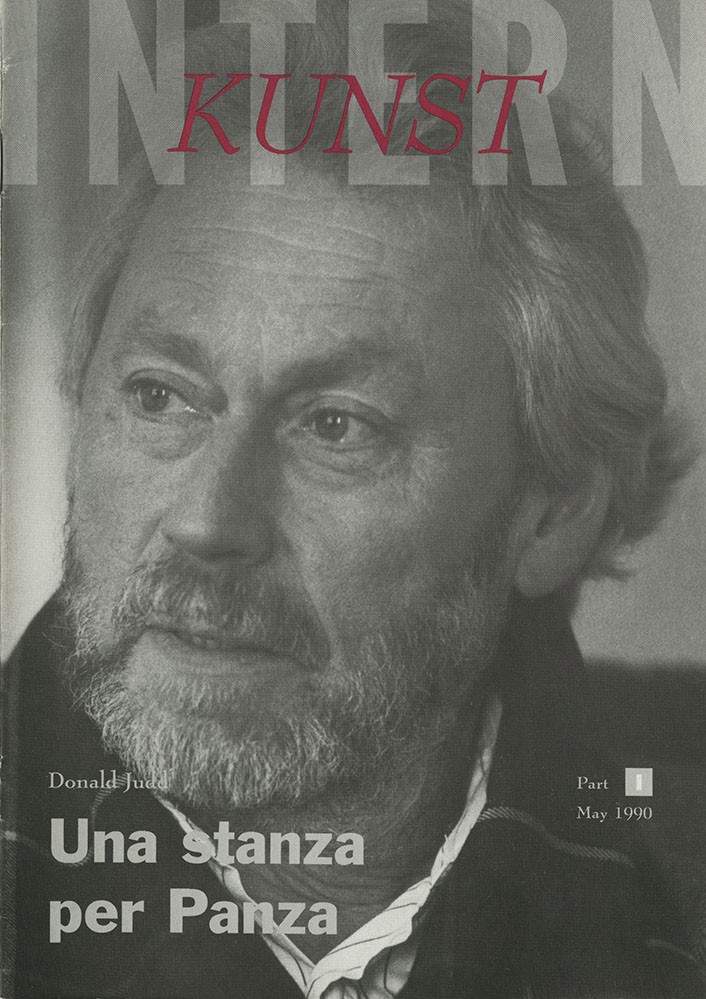

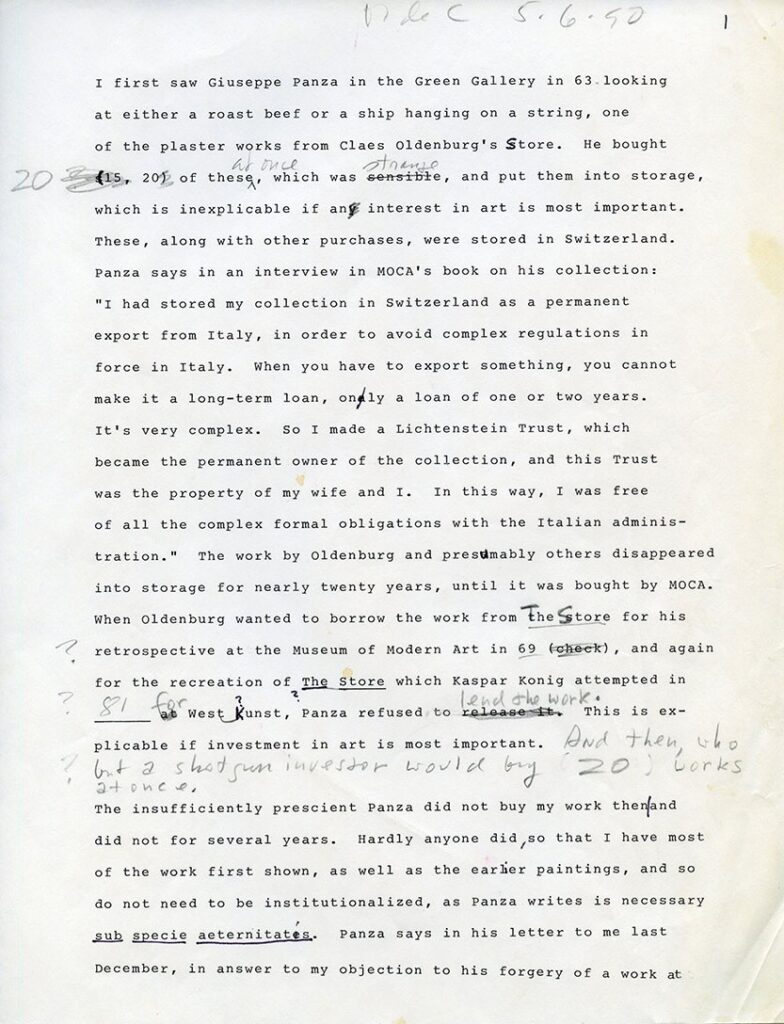

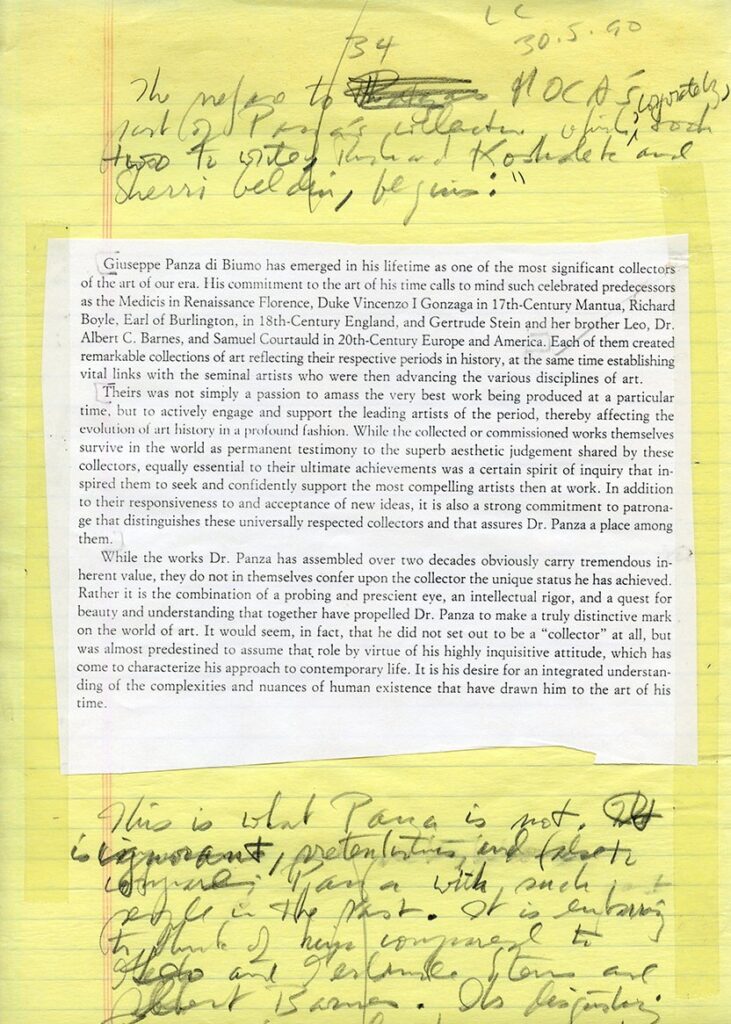

Whereas his shorter reviews were often written in one draft, Judd often produced many handwritten and typed drafts for essays of this length like the typed draft with handwritten annotations below.

Una stanza per Panza: Part I (Kunst Intern, May 1990). Courtesy Judd Foundation Archives

Donald Judd, typed draft with handwritten annotation of “Una stanza per Panza,” June 5, 1990. Donald Judd Papers, Judd Foundation Archives, Marfa, Texas

In this handwritten page, Judd cut and pasted a large section of text from Richard Koshalek and Sherri Geldin’s preface to Art of the Sixties and Seventies: The Panza Collection. The bracketed text denotes the section that Judd quoted from in “Una stanza.”

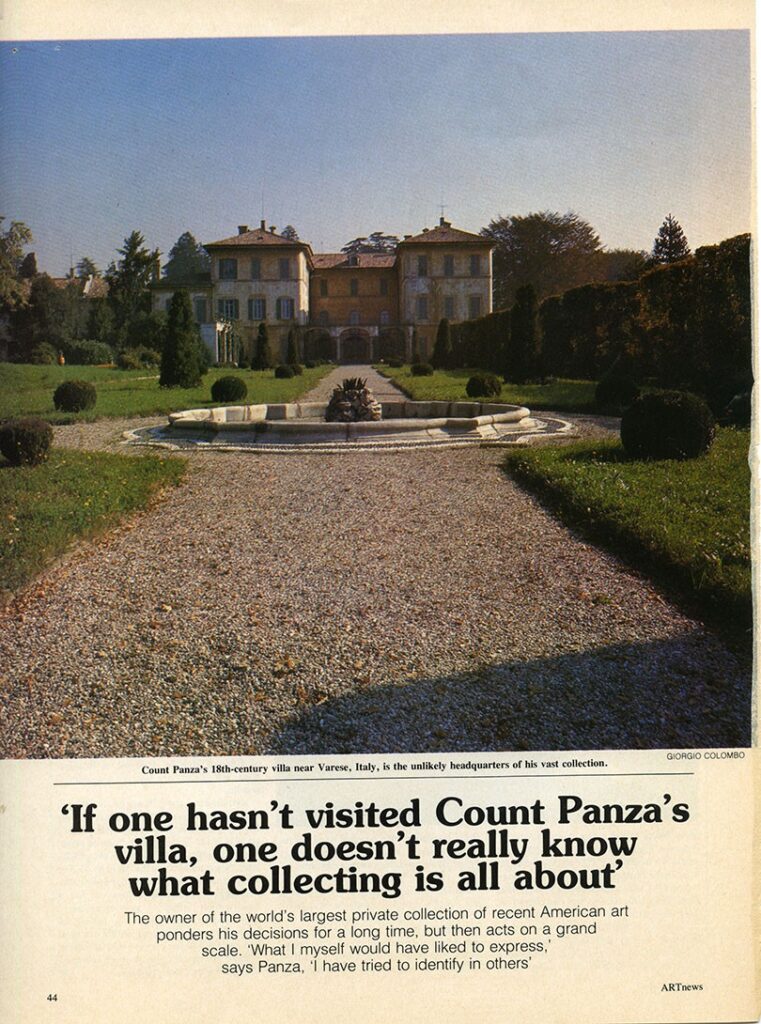

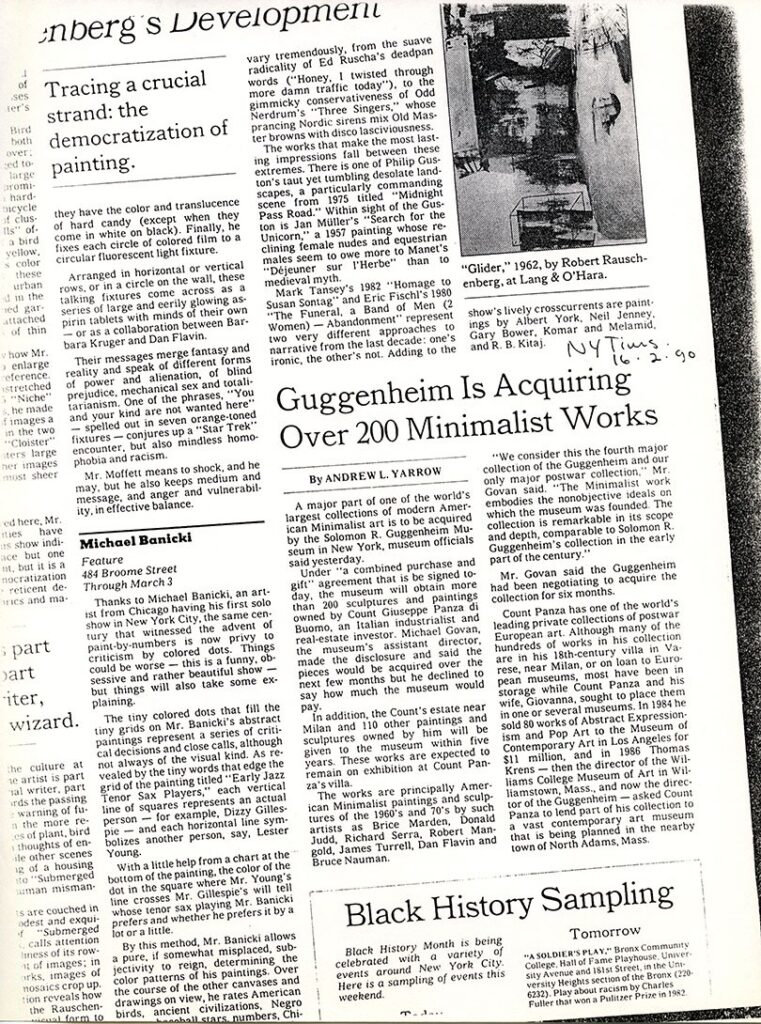

Included in Judd’s “Panzata” were articles with and interviews given by Panza as well as articles related to museums that were acquiring works from Panza as seen below in a December 1979 article on Panza from ARTnews and a photocopy of a New York Times article from February 1990 on the Guggenheim Museums’s acquisition of more than 300 works from Panza. The multi-part sale eventually totaled $32 million.

Donald Judd, handwritten draft of “Una stanza per Panza,” May 30, 1990. Donald Judd Papers, Judd Foundation Archives, Marfa, Texas. Donald Judd Papers, Judd Foundation Archives, Marfa, Texas

Milton Gendel, “‘If One Hasn’t Visited Count Panza’s Villa, One Doesn’t Really Know What Collecting Is All About,’” Art News, December 1979, pp. 44. Courtesy Judd Foundation Archives

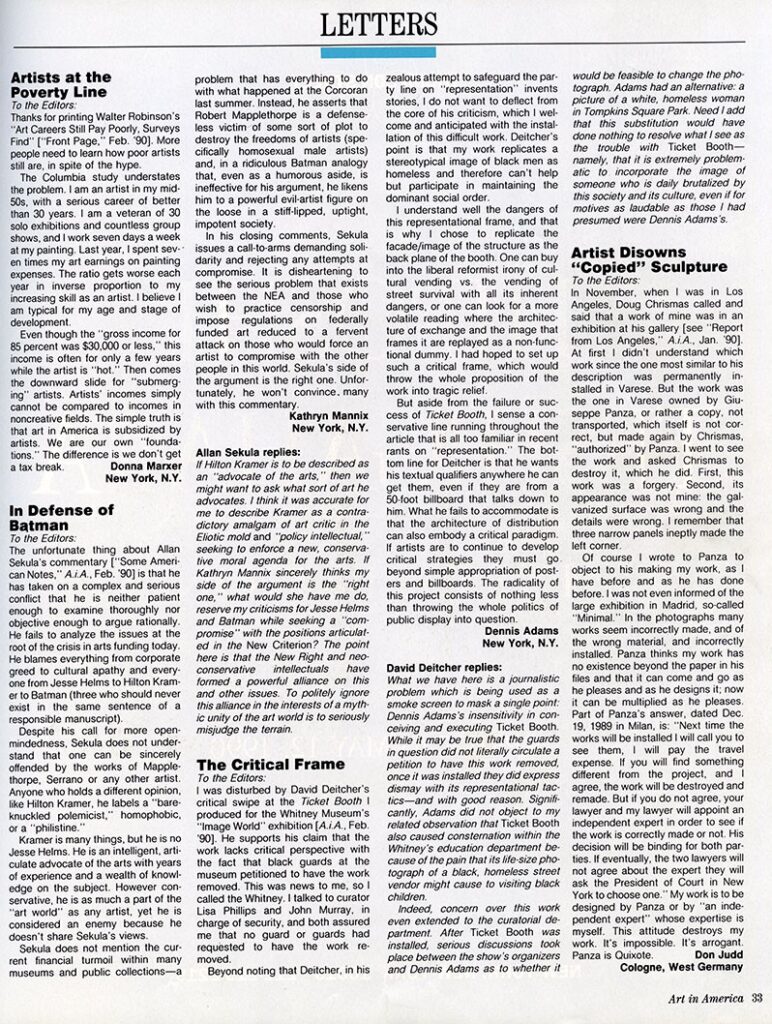

In addition to “Una stanza per Panza,” Judd made other efforts to inform the public of Panza’s forgeries of his work, including a Letter to the Editors of Art in America in April 1990 (far right column). In the same issue was another announcement of the Guggenheim Museum’s acquisition of the Panza Collection (see “Guggenheim Gets Panza Trove”). As Judd wrote of the purchase in “Una stanza”:

When the Guggenheim didn’t buy my work for thirty years, I wasn’t important to them. When now they will buy that work, I’m still not important to them, because they are not interested in present work. My lack of importance is mysteriously always in the present, rolling on, a problem unbureaucratically solved by death, but happily for the art and museum business.

Andrew L. Yarrow, “Guggenheim Is Acquiring Over 200 Minimalist Works,” New York Times, February 16, 1990, Section C, Page 30. Courtesy Judd Foundation Archives

Donald Judd, “Artist Disowns ‘Copied’ Sculpture,” Art in America, April 1990. Courtesy Judd Foundation Archives

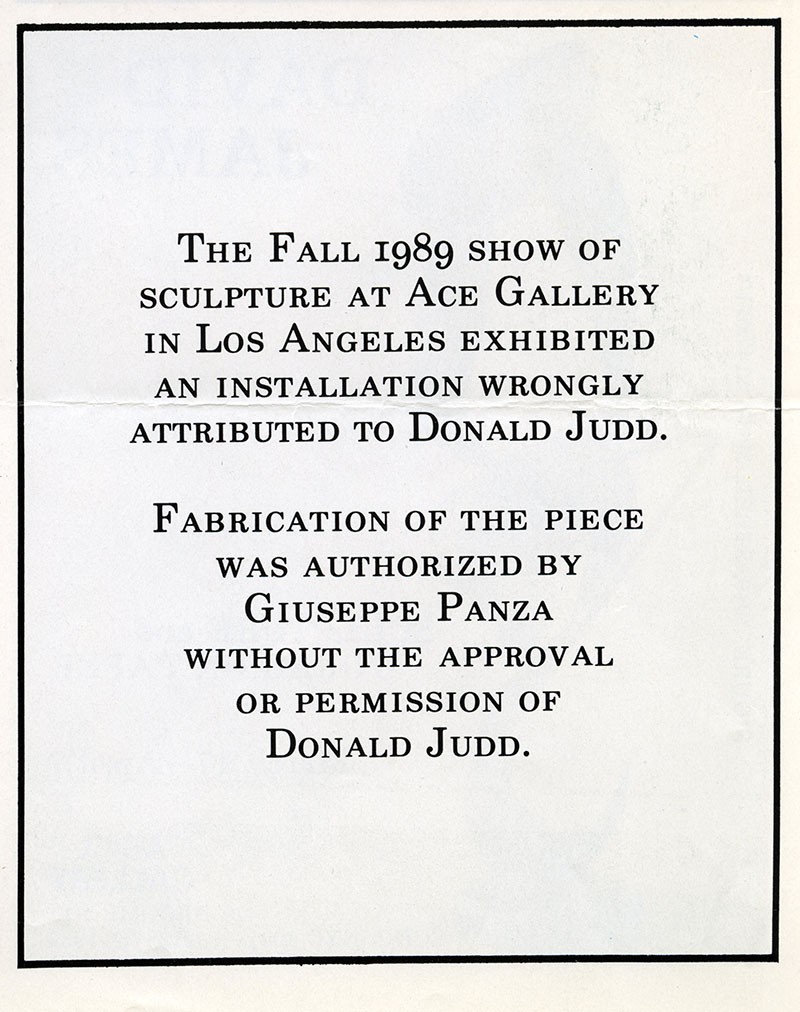

Furthermore, in the March 1990 issue of Art in America, Judd took out the following advertisement:

Walter Robinson, “Guggenheim Gets Panza Trove,” Art in America, April 1990. Courtesy Judd Foundation Archives

Donald Judd, [advertisement], Art in America, March 1990

In addition to published material, Judd also kept notes and photographs by his studio assistants on the material, assembly, and installation of works which Panza had made without his supervision. The photograph below documents a work with eight units in hot-rolled steel that was exhibited at the first public survey of the Panza Collection at the Kunsthalle in Düsseldorf in 1980. Notes from Judd’s studio indicate the problems with the fabrication including: “great variation in color and textural appearance…work appears rougher than Don’s usual mill surfaces” and “bottom flange independent resting within sides and in front of recessed panel, contrary to Don’s practice and idea.”

Photograph of an eight-unit object in hot-rolled steel. Courtesy Judd Foundation Archives.

This was one of fifteen objects that were decommissioned by the Guggenheim Museum after extensive research was conducted by the Panza Collection Initiative (PCI). As noted on PCI case study website for Donald Judd, “Under these new guidelines decommissioned objects will be retained only as artifacts for future study.”

The PCI, established in 2010, was a multi-year project focused on the technical history of works acquired from Giovanna and Giuseppe Panza di Biumo by the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. Case studies of this research have been recently published by the Guggenheim in Object Lessons: Case Studies in Minimal Art – The Guggenheim Panza Collection Initiative. In addition to the Solomon R. Guggenheim Archives, the Giuseppe Panza papers, and numerous public and private archives, the PCI team conducted interviews with Judd’s fabricators, gallerists, and assistants, and examined Judd’s records and the records of his studio held in the Judd Foundation Archives.

As Judd makes clear in “Una stanza per Panza,” the implications of the unauthorized fabrication of his work by Panza were far-reaching:

Many supposedly interested in art are not going to understand. I think the situation has declined so far that even many artists will not understand, as can be foretold by their work. Panza, many, have no respect for art, the artists, for the integrity of the activity… Art doesn’t have to exist; there is no assurance that it continue. It has lapsed before and is disappearing now.

In this way, in addition to documenting the unscrupulous behavior of one collector, Judd’s “Panzata” provides an example for artists living and working now of how to object to, as he wrote, “attitudes which are destroying visual art.”