In an interview from 1989 Donald Judd stated:

“While I was in the army, the US Army, for a year and a half – World War II had only been over a year – they gave the soldiers all sorts of books, paperbacks. This was the beginning of educational paperbacks in the United States. The books were usually just dumped in a corner in an empty barrack, so I used to take them. I traveled with a pretty good library. One of the books was a history of Russia by Bernard Pares. I probably read it three times. There wasn’t much to do. And I was very interested in it, I like reading history. So I knew Russian history pretty well at 18. And also there was a lot of Russian literature, Chekhov, Turgenev, Tolstoy.”

Over the following decades, Judd wrote a number of essays on Russian artists, including “Kandinsky and his Citadel,” a review of the exhibition, Vasily Kandinsky, 1866–1944: A Retrospective Exhibition, at the Solomon R.Guggenheim Museum in 1963; a review of Kazimir Malevich, an exhibition in 1963 also at the Guggenheim Museum; and in 1981, a long essay “Russian Art in Regard to Myself,” on the importance of Russian art of the early twentieth century for Art Journal.

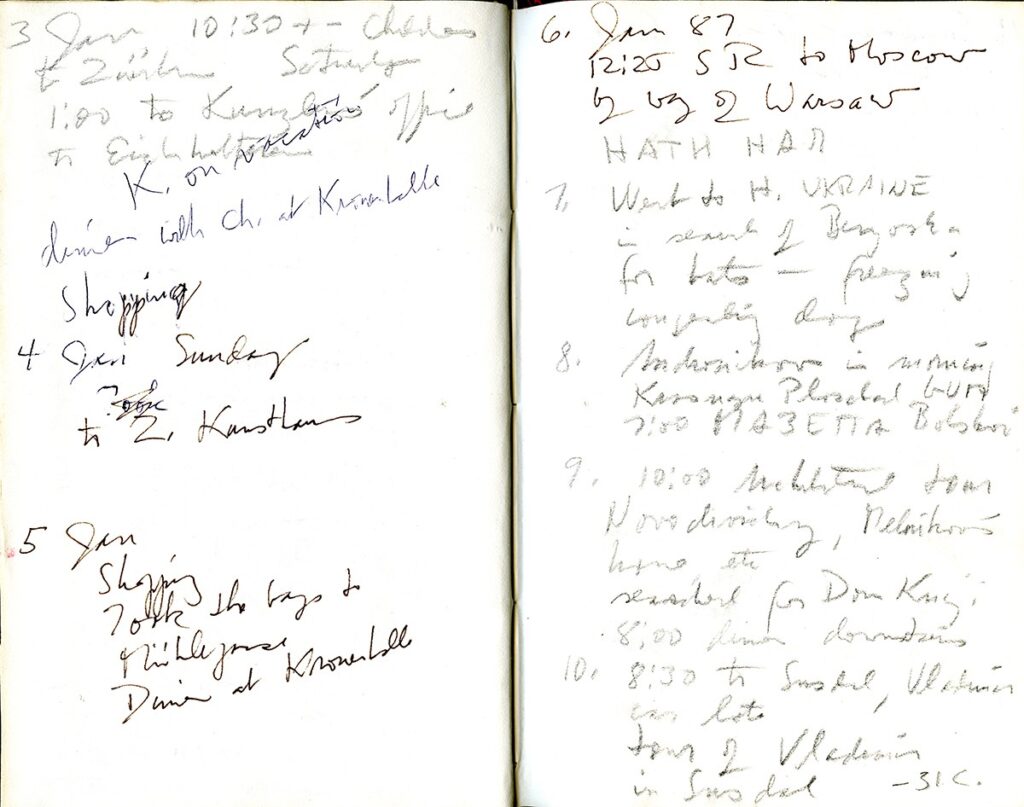

Judd’s library at La Mansana de Chinati/The Block in Marfa, Texas demonstrates his extensive interest in Russian architecture; he collected over two dozen books on this topic including Uses and Tradition in Russian and Soviet Architecture (London: Architectural Design, 1987) and Architecture of the Soviet Russia (Moscow: Strolizdat, 1987). The bulk of his writing on Russian architecture appears after a January 1987 trip that he took with his son and daughter to the then Soviet Union, one of four he made during his lifetime.

Recounting his trips to Russia, Judd stated in 1989:

I’ve been to Russia, yes, twice, to Estonia and then to Leningrad. That was a few years ago. About two years, a year and a half ago, I went with my two children for three weeks to Moscow, Leningrad and the old towns, Suzdal, Yaroslavl, Novgorod and so on [January 1987]. But other than that I haven’t been to the Eastern countries. It’s very interesting. It was extremely cold. – 46°C for a few days in Suzdal.

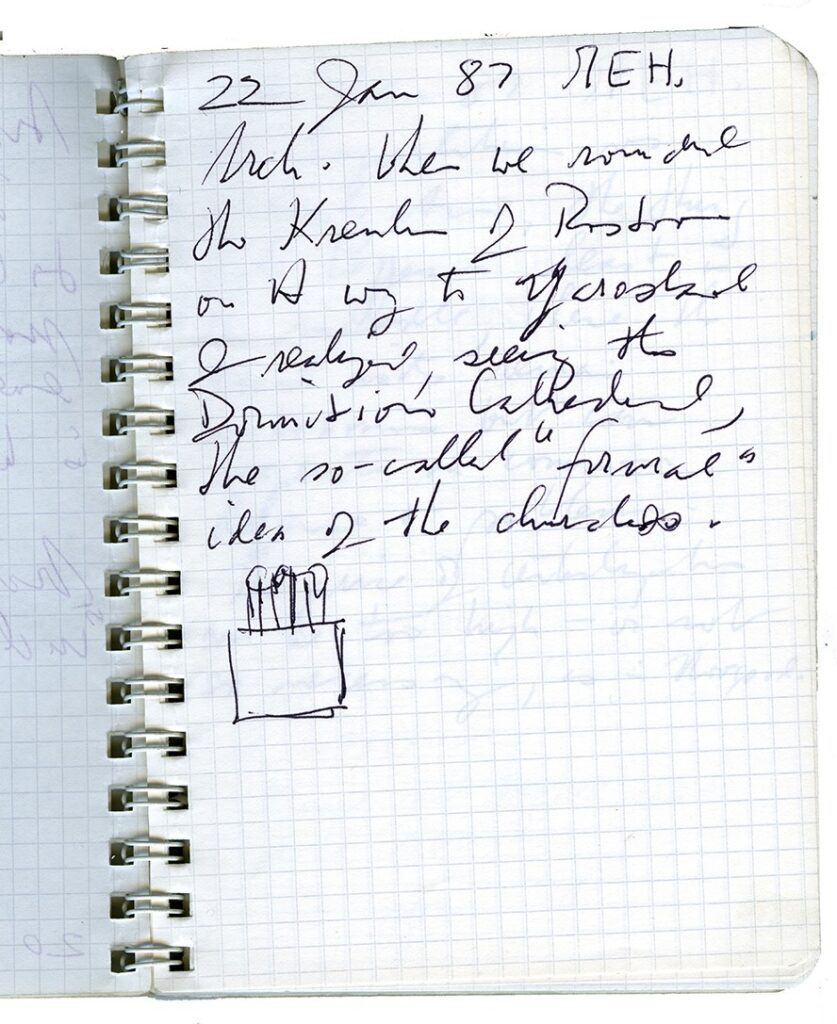

Excursions to various cities often involved visiting the churches in each place and recording their various characteristics. One thought Judd jotted down in a small, blue, spiral-bound notebook while in Rostov, Russia, reads: “22 Jan 87: When we rounded the Kremlin of Rostov on the way to Yaroslavl I realized, seeing the Dormition Cathedral, the so-called ‘formal’ idea of the churches.” Rostov, founded in 862, is one of the oldest towns in Russia.

While traveling in Russia in January 1987, Judd’s daughter, Rainer, took dozens of photos documenting the places they visited.

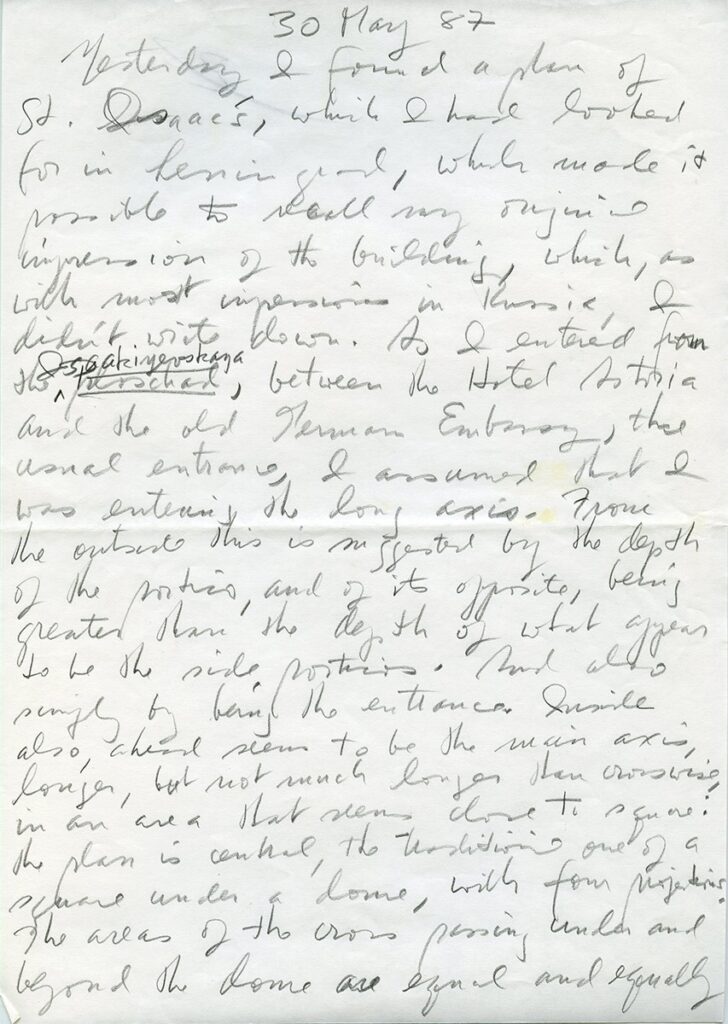

With their similar apses, domes, and arcades, many of these churches shared key architectural features. For example, many of the large cathedrals Judd visited, including the Cathedral of the Dormition in Rostov, share an arrangement of drums and cupolas. In a lengthy note, written in May 1987 as a reflection on St. Isaac’s Cathedral in St. Petersberg, still known as Leningrad at that time, Judd wrote:

“Yesterday I found a plan of St. Isaac’s, that which I had looked for in Leningrad, which made it possible to recall my original impressions of the building, which, as with most impressions in Russia, I didn’t write down…The whole makes a simple and complex cross, from the outside, open in the deep porticos as opposed to closed in the chapels and in the shallow porticos, and from the inside, broad and open opposed to longer, less wide, and closed, opening in stages as you walk crosswise.This is of course a variation on an old idea, made too late, but as space, as architecture, it’s pretty good, not great. But it might have been great if the materials and the details had been equal to the plan.”

A late Neoclassical interpretation of a Byzantine Greek-cross church constructed over a forty-year period from 1818 to 1858 under the supervision of Auguste de Montferrand (1786-1858), St Isaac’s is the largest Russian Orthodox Church in the city and the fourth largest cathedral in the world. Recalling his visit, Judd wrote, “In January, the coldest of this century, someone had placed a rose on the plinth of the bust of the architect Ricard de Montferrand, who began the building in 1818 and finished it in 1858, and then died.”

In addition to his visits to Russian churches, Judd and his family made a memorable visit to the home of architect and painter, Konstantin Melnikov (1890-1974), as noted here in his itinerary for January 9, 1987.

Melnikov’s home, a cylindrical building in the heart of Moscow was built between 1927 and 1929, a period in which Melnikov realized ten buildings. As Flavin Judd, Judd’s son, recalled in a recent interview, “We saw Konstantin Melnikov’s house in Moscow, which was incredible. I didn’t know what it was at the time, but it was gorgeous.”

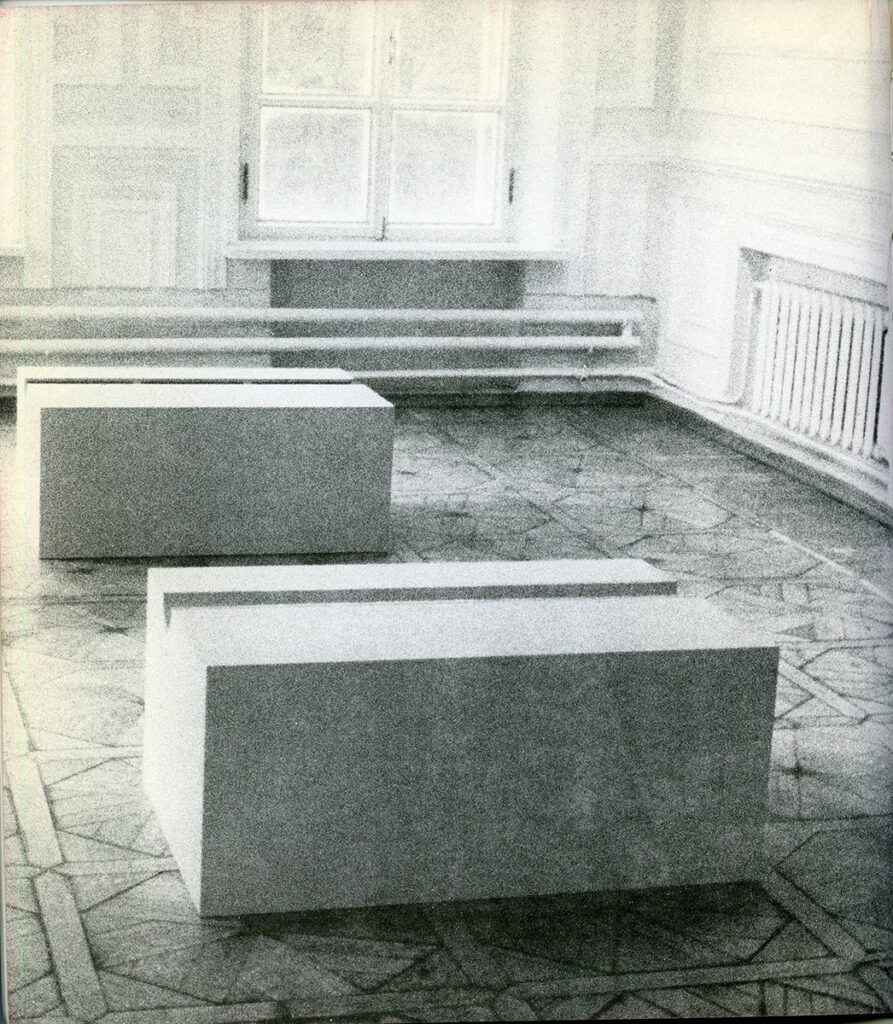

Judd made two additional trips to Russia in January and August 1990. He had his first and only exhibition in Russia at the Soviet Cultural Federation in Moscow opening in August 1990.

Judd was one of the first Western artists to exhibition in Russia and at this point very little documentation exists of the show. This exhibition served as an example for a later exhibition, realized in 1994 at Galerie Gmurynska, of works that had appeared in this inaugural Russian exhibition. While the 1994 show featured Judd’s works as well as two drawings by Kazimir Malevich, a recent 2017 exhibition curated by Flavin Judd, also at Galerie Gmurzynska, included 20 drawings and two paintings by the Suprematist artist and also featured a cadmium-red floor piece by Judd that was shown in the original exhibition in Moscow.

Judd’s work in architecture began while he was in the Army, serving as an engineer, and continued in his own spaces in New York and Marfa and in projects throughout North America and Europe. These projects, often done in collaboration with architects, included the Bahnhof Basel/Peter Merian Haus in Switzerland and the Kunsthaus Bregenz in Austria. An exhibition of several of Judd’s architecture projects is now on view at the Center for Architecture in New York.