Judd’s canonical and provocative essay “Specific Objects” is published in Arts Yearbook 8. Judd later clarifies that “despite what people think, [it] was not meant to be a doctrinaire, dogmatic, or definitive, or anything article. . . . ‘Specific Objects,’ which is my title, and I liked, isn’t meant to be about my work; it’s just meant to be about any of that kind of thing that isn’t painting or sculpture.” In the article, he states, “Actual space is intrinsically more powerful and specific than paint on a flat surface. . . . It isn’t necessary for a work to have a lot of things to look at, to compare, to analyze one by one, to contemplate. The thing as a whole, its quality as a whole, is what is interesting.”

In January, Judd is hired by James Fitzsimmons, editor of Art International, to cover exhibitions for $10 a review, roughly fifteen shows per issue.

Judd exhibits his first round-front progression (DSS 45) in a group show at Byron Gallery, New York. (A round-front progression has bullnose-shaped boxes that project face-front from a square tube.) DSS 45 is lacquered in Harley Davidson HiFi Red, a paint favored by Judd for its transparent quality.

Judd participates in his first group exhibition outside the United States, Polychrome Construction: Judd, Weinrib, Burton, Rayner, Snow, Weiland, at The Isaacs Gallery, Toronto. This is curator Brydon Smith’s introduction to Judd’s work, although the two don’t meet until a few years later. (Smith and Judd will later collaborate on multiple exhibitions and the publication of the 1975 volume Donald Judd: Catalogue Raisonné of Paintings, Objects, and Wood-Blocks 1960–1974.) The Isaacs Gallery show attracts press attention because Dr. Charles Comfort, director of the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, refuses to classify four Judd works as art. As a result, the gallerist, Av Isaacs, has to pay a duty on their importation. Comfort also denied the designation of art to Andy Warhol’s Brillo boxes and Campbell’s soup cans. The following year, the Canadian prime minister appoints Jean Sutherland Boggs as the first female director of the National Gallery of Canada, which will subsequently host retrospectives of both Dan Flavin and Judd.

In March, Judd writes his last review for Arts Magazine. Focused on Lee Bontecou’s reliefs, the piece proclaims, “Lee Bontecou was one of the first to use a three-dimensional form that was neither painting nor sculpture. Her work is explicit and powerful.”

On April 7, Judd orders his first single stack (DSS 64), made in galvanized iron, and first large stack (DSS 65), a wall work with seven units in galvanized iron (an eighth unit is added later) from Bernstein Brothers. The works are completed June 22. A stack is a multi-unit, vertical wall work, most often consisting of ten identical units installed with a specific interval (the negative space between each unit) equal to the height of one unit. The space between the floor and the bottom of the lowest unit measures the same as each unit of the stack. A single-unit stack measures six by twenty-seven by twenty-four inches and is wall mounted. Both forms are often used in Judd’s oeuvre.

On April 21, Judd’s relationship with Arts International ends when he receives a letter from editor James Fitzsimmons stating, “What you’re sending me is not what I want. It’s not what you say that bothers me—I have always held the critic should be allowed to call his shots as he sees them—it’s the way you say it, or at least the way you say it some of the time. I like your writing best when you settle down, dig in, and do a good square job of work; I don’t like it when you talk off the cuff, it’s too ‘informal’ for my taste.”

In April, Judd receives a travel grant from the Swedish Institute of Stockholm, which facilitates his first trip to Europe.

Judd has his last show with Green Gallery, Flavin, Judd, Morris, Williams. Green Gallery shuts its doors in July. Judd enters a new gallery relationship with Leo Castelli, whose eponymous gallery is located at 4 East Seventy-Seventh Street on Manhattan’s Upper East Side.

At the VIII Bienale de São Paulo, the United States is represented by the work of Judd along with that of Barnett Newman, Larry Bell, Billy Al Bengston, Robert Irwin, Larry Poons, and Frank Stella. The exhibition is curated by Walter Hopps; it travels to The National Collection of Fine Arts, Smithsonian Institution. The following January, the Newmans, Judd and Finch, Larry Poons and Lucinda Childs, Dan Flavin, Larry Bell, and Frank Stella travel to the U.S. opening in Washington, DC.

On December 8, Judd is interviewed by Lucy Lippard and Bruce Glaser as a follow-up to “New Nihilism or New Art?” Quoting from the original broadcast, Glaser and Lippard ask Judd for clarification concerning his statements on nonhierarchical composition and his issues with the term “reductive” as it applies to his own work. Judd responds, “Because it’s only reduction in these things that someone doesn’t want. If my work is reductionist or something, it’s because it doesn’t have the elements that people think should be there, and it has other elements.”

Having received a monthly stipend against sales from Leo Castelli Gallery since November, Judd participates in his first group exhibition at the gallery. Judd shows a single-unit galvanized iron work with bullnose sides (DSS 63).

1965 Exhibition Summary

In addition to having his work exhibited at seven museums, Green Gallery’s last show, and Leo Castelli Gallery, Judd has work included in group shows at seven other commercial galleries in Canada and the United States. He gains important international recognition by representing the United States in the VIII Bienale de São Paulo; having work included in a group show at the Moderna Museet, Stockholm; and receiving a travel grant from Sweden that makes his first trip to Europe possible.

Judd’s first solo exhibition at Leo Castelli Gallery, Don Judd, consists of five wall works (DSS 56, DSS 74, DSS 78, DSS 80, and DSS 84) and two floor works (DSS 76 and DSS 78). Reviews appear in Architectural Forum, ARTnews, and Studio International, along with pieces in The New York Times by Hilton Kramer, Arts Magazine by Mel Bochner, and Art International by Lucy Lippard. Kramer questions, “What is a work of art? Is it something the artist actually makes with his own hand, or is it something he only conceives and then leaves to other, more expert hands (and machines) than his own physical realization? These are the questions that remain uppermost in one’s mind in confronting the new work by Donald Judd installed at Leo Castelli Gallery, 4 E 77th Street . . . it is work that consigns to the trash can of history most of our conventional beliefs about sculptural craftsmanship and the artist’s role in creating his own esthetic object.”

Judd participates in Primary Structures: Younger American and British Sculptors at the Jewish Museum, New York. Organized by curator Kynaston McShine, the exhibition introduces a particular group of artists who have in common the use of industrial materials and simplified forms. In addition to Judd, the group includes Dan Flavin, Robert Smithson, Ellsworth Kelly, Tony Smith, John McCracken, Judy Chicago, Anne Truitt, Robert Morris, Larry Bell, and Sol LeWitt, among others. In his essay for the catalogue, Judd objects to the term “minimalism” and the categorization of artwork by critics such as Barbara Rose, who has recently published the controversial article “ABC Art” in Art in America.

On May 2 Judd participates in “The New Sculpture,” a symposium at the Jewish Museum. Panelists include Donald Judd, Mark di Suvero, Robert Morris, and Barbara Rose, among others. During the discussion, moderated by Kynaston McShine, di Suvero remarks that Judd “cannot qualify as an artist because he doesn’t do the work.”

In July, Judd is a visiting/teaching artist at Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire, where he exhibits his first indoor piece that is site-relational—directly relating to the space in which it is installed (DSS 87). The work is “a row of six or eight boxes—it can vary—between two sidewalls, on the wall.”

Judd is included in Eight Sculptors: The Ambiguous Image at the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis. The artists include Christo, Robert Morris, Claes Oldenburg, Lucas Samaras, George Segal, Ernest Trova, and H. C. Westermann.

Judd’s work is included in Vormen van de Kleur, an exhibition organized by Edy de Wilde and Wim Beeren. Originating at the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, the exhibition travels the following year to the Württembergische Kunstverein, Stuttgart, and the Kunsthalle Bern.

1966 Exhibition Summary

Judd’s work is represented in fourteen group exhibitions, including Carl Andre, Jo Baer, Dan Flavin, Don Judd, Sol LeWitt, Agnes Martin, Robert Morris, Ad Reinhardt, Robert Smithson, Michael Steiner, Dwan Gallery, New York, and Contemporary Sculpture Selection and Annual Exhibition 1966: Sculpture and Prints, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. He has two solo exhibitions: Don Judd, Leo Castelli Gallery, New York, and Donald Judd Visiting Artist, Hopkins Center Art Galleries at Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire.

On January 27, Judd orders his first small stack utilizing plexiglass (DSS 93) to be fabricated by Bernstein Brothers. A twelve-unit large stack with galvanized iron and green lacquer on the front and sides of each unit (DSS 104) is ordered at the same time. Judd will continue to use plexiglass throughout his life.

As part of Angry Arts Week, a protest against the Vietnam War from January 29 through February 4, Judd and some five hundred artists such as Carolee Schneemann, Mark di Suvero, Nancy Graves, Roy Lichtenstein, James Rosenquist, and Richard Serra participate in the exhibition Collage of Indignation, a multimedia collection of works displayed at the Loeb Center, New York University. Works include sculpture, poetry, drawings, performance, paintings, film, and photography.

In February, Judd has a solo exhibition at Ferus Gallery, Los Angeles. This is his first show on the West Coast.

Judd’s essay “Jackson Pollock” is first published in the April issue of Arts Magazine. He declares, “Art criticism is very inferior to the work it discusses. . . . A thorough discussion of Pollock’s work or anyone’s should be something of a construction. It’s necessary to build ways of talking about the work and of course to define all of the important words. Most discussion is loose and unreasonable. The primary information should be the nature of his work. Almost all other information should be based on what is there. This doesn’t mean that the discussion should only be ‘formalistic.’ Almost any kind of statement can be derived from the work: philosophical, psychological, sociological, political. Such statements, usually nonsense, should refer to specific elements in the work and to any statements of biographical information that might be relevant. Certainly, the discussion should go beyond formal considerations to the qualities and attitudes involved in the work.”

In May, Judd shows a wall work (DSS 87) in 10, a landmark exhibition at Dwan Gallery, Los Angeles; it was previously exhibited at Dwan Gallery, New York, in October 1966.

Judd’s first three-dimensional work in edition, a metal object to be placed on a table or floor for the Ten from Castelli portfolio, is completed. It is produced in an edition of two hundred with forty artist’s proofs published by Tanglewood Press. In addition to this work, the box includes works by Lee Bontecou, Jasper Johns, Roy Lichtenstein, Robert Morris, Larry Poons, Robert Rauschenberg, James Rosenquist, Frank Stella, and Andy Warhol. Judd continues to make occasional works in edition for the rest of his life.

Judd participates in an exhibition in his home state for the first time. 7 for 67: Works by Contemporary American Sculptors is curated by Emily Rauh for the City Art Museum of St. Louis. The show includes work by Christo, Mark di Suvero, Claes Oldenburg, Lucas Samaras, George Segal, and Ernest Trova. A symposium, “7 for 67,” moderated by Rauh, includes Judd, di Suvero, and Trova. During the conversation, in response to Rauh’s question, “Aren’t you also making pieces for a kind of space?” Judd states, “Yes, to some extent, varying from piece to piece. They need a good deal of space around them. Sometimes they have to do with a particular dimension of a room, sometimes they don’t. And they could have even more to do with a particular dimension of a room, but again, that gets into something more ambitious, making your own room and so forth.”

In October, Judd is in a group show at Irving Blum, Los Angeles.

Judd conducts seminars in his Nineteenth Street studio for the Whitney Independent Study Program, through which he meets the young painter Jamie Dearing. Dearing begins working as Judd’s studio assistant shortly thereafter.

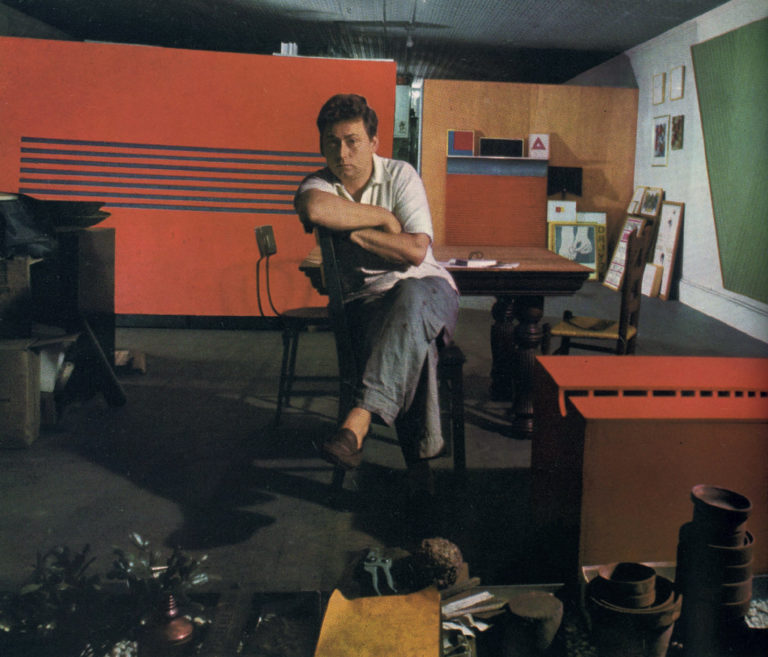

After an interview with Judd conducted by art critic Joanna Eagle for Art in America, she writes, “Primary structurist Donald Judd is just starting and building a collection mainly by exchange and, as he says, lucky accidents. . . . Though small now, Judd’s collection will probably be first-rank in ten years or so.” A photograph of Judd’s fourth-floor living/studio loft shows Frank Stella’s Valparaiso Green, Judd’s DSS 27 installed on the back wall, and DSS 41 in the foreground.

On December 18, Barbara Rose conducts an interview with Judd and Frank Stella. Rose questions Judd, “You said that your work is not sculpture. If it isn’t sculpture, what is it?” Judd replies, “I don’t know what it is, and I don’t feel that I have to give it a title. So I don’t feel required to say what it is.”

1967 Exhibition Summary

Judd’s work is shown in one solo show at Ferus Gallery, Los Angeles, and twenty-five group exhibitions, including Primary Structures: Younger American and British Sculptors at the Jewish Museum, New York; American Sculpture of the Sixties, Los Angeles County Museum of Art; A New Aesthetic, The Washington Gallery of Modern Art; and Guggenheim International Exhibition: Sculpture from 20 Nations, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York.

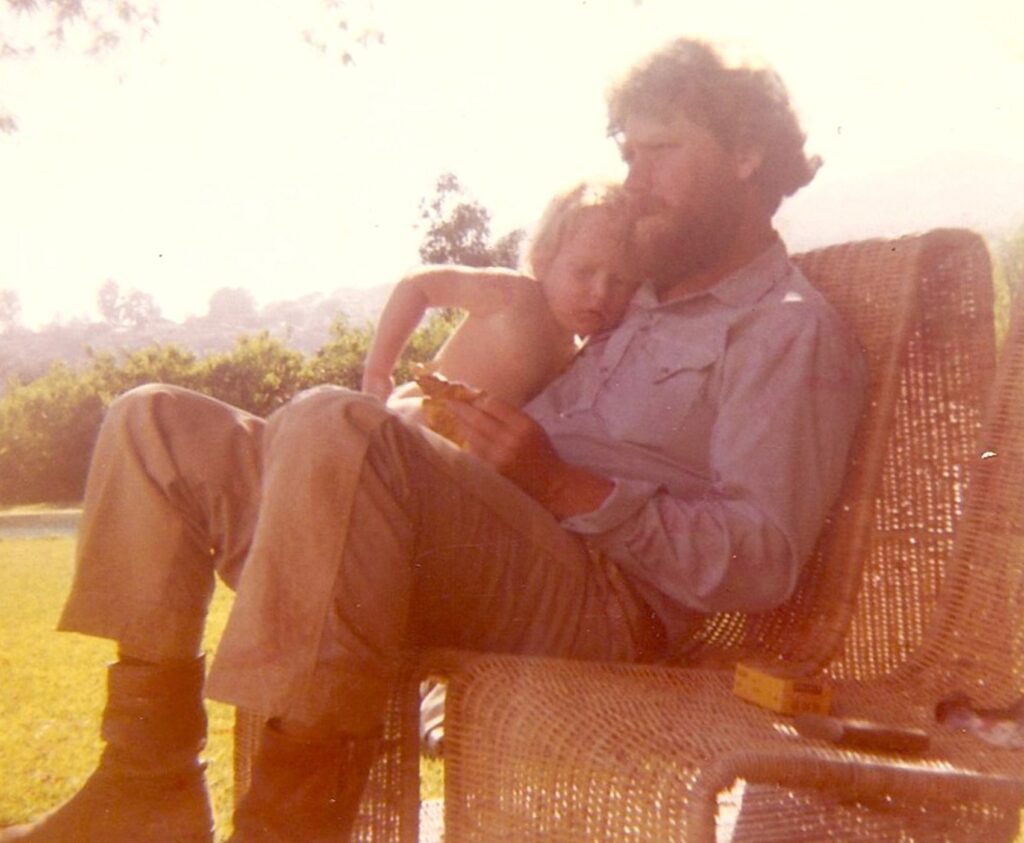

Son Flavin Starbuck Judd is born in New York on January 23. His first name references the artist Dan Flavin, while Starbuck is a maternal family name.

Judd is included in First Triennale – India at the Lalit Kala Akademi and National Gallery of Modern Art, New Delhi, India. His work, a blue-lacquered square-front progression (DSS 115), receives honorable mention. This is Judd’s first show in East Asia.

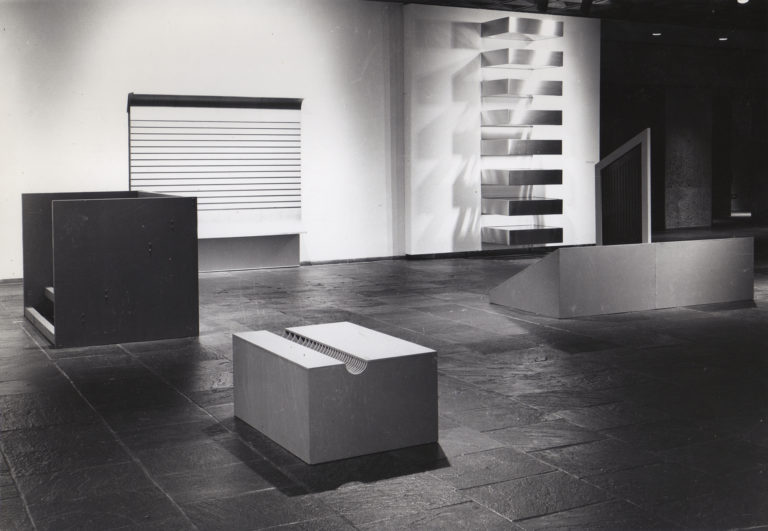

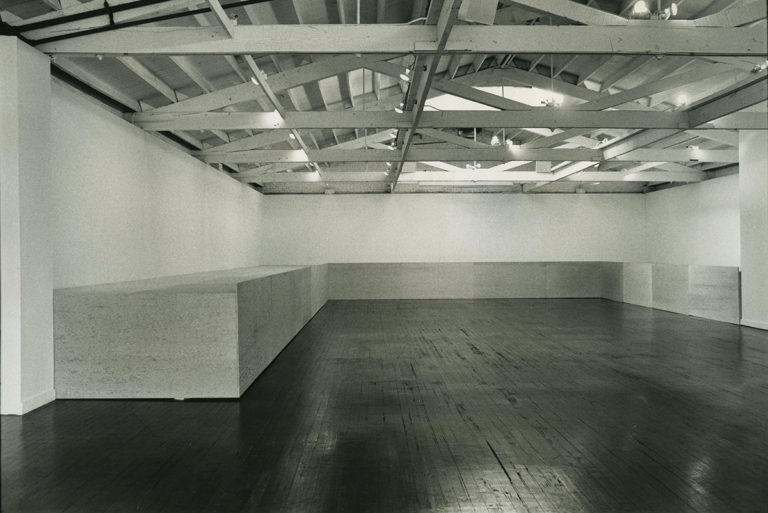

Don Judd, a major survey exhibition of Judd’s work from 1962 to 1968, organized by curator William C. Agee, assisted by Dudley Del Balso, opens at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York (February 27–March 24, extended through April 14). It includes drawings and thirty-one works. Having a comprehensive solo exhibition at such a young age (forty years old) results in Judd receiving “many overtures . . . from foreign curators and dealers at the time of the show.”

Image: Installation view, Don Judd, Whitney Museum of American Art, February 26–March 24, 1968. Photo Rudolph Burckhardt. Courtesy Whitney Museum of American Art.

Dudley Del Balso becomes Judd’s first studio manager, a position now required by the sharp increase in Judd’s activities in the art world. She establishes a running record and purchase order system that becomes the basis of Judd’s 1975 catalogue raisonné, for which she becomes one of three editors. Del Balso continues to work with Judd until 1984.

Judd exhibits five major works at Documenta 4 in Kassel. The exhibition includes 151 international artists.

Judd’s work is included in The Art of the Real: USA 1948–1968, originating at The Museum of Modern Art, New York. The exhibition travels to the Grand Palais, Paris; Kunsthaus Zürich; and Tate Gallery, London.

In August, Judd leads an artists’ workshop at Rapid River Lodge, as part of the Emma Lake Artist’s Workshops held each summer at Lac la Ronge, Saskatchewan. The workshops were begun in 1955, each with a workshop leader. Prior to Judd, workshop leaders included painters Will Barnet, Barnett Newman, Frank Stella, Kenneth Noland, art critics Clement Greenberg and Lawrence Alloway, and composer John Cage.

Judd is an artist in residence at the Aspen Center for Contemporary Art in August. Judd and Finch buy ad space in the Aspen Times and publish a War Resisters League poster.

Roberta Smith meets Judd in the fall while spending a semester in New York during her senior year at Grinnell College. She is enrolled concurrently in the Whitney Independent Study Program, for which she writes a paper on Judd’s transition from painting to three-dimensional work. Preparatory to the paper, she interviews him in his second-floor studio on Nineteenth Street, develops a friendship with him, and eventually becomes one of three editors of the 1975 volume Donald Judd: Catalogue Raisonné of Paintings, Objects, and Wood-Blocks 1960–1974.

Paula Cooper Gallery, the first art gallery in SoHo, New York, opens in 1968 with the October exhibition Benefit for the Student Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam. The show includes work by Judd, Carl Andre, Dan Flavin, Robert Mangold, and Robert Ryman, along with Sol LeWitt’s first wall drawing. Judd exhibits a brass floor piece with a recessed top (DSS 143). This piece is purchased by Philip Johnson and accessioned into the permanent collection of The Museum of Modern Art, New York, in 1980.

In October, Judd customizes his Land Rover, working with Bernstein Brothers to manufacture built-in cabinetry to his specifications.

Judd receives a 1968 Guggenheim Fellowship from the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation “to continue producing large-scale works in plastic and steel.”

On November 26, Judd and Finch purchase an 1870 cast-iron building located at 101 Spring Street in the SoHo neighborhood of New York. The building, designed by Nicholas Whyte, is five stories with two additional basement levels. Judd purchases it from Housing for Cultural Activities, Inc. for $68,000. The Empire Embroidery Company continues to rent temporarily on the fifth floor. Judd begins a renovation of the building, designating a different use for each floor. Over the years, he permanently installs work of his own and that of others throughout the building: “The idea of large permanent installations, which I consider my idea,” he later writes, “began in a loft on Nineteenth Street in New York and developed in a building I purchased in the city in 1968.”

1968 Exhibition Summary

Judd has work included in a solo exhibition at Irving Blum Gallery, Los Angeles, and seventeen group shows, three of which take place wholly in, or travel to, Europe: Minimal Art, Gemeentemuseum, The Hague; Documenta 4, Kassel; and The Art of the Real: USA 1948–1968, which originates at The Museum of Modern Art, New York (subsequently traveling to museums in Paris, Zürich, and London). In addition, Judd has his first major solo museum exhibition, a full survey of his work to date, Don Judd, curated by William C. Agee, at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York.

Leo Castelli Gallery presents the solo exhibition Don Judd. The show includes two works: a clear anodized aluminum tunnel piece lined on the interior with blue plexiglass (DSS 159) and a thirty-nine-unit galvanized iron work, installed in thirteen rows, stacked three units high, often referred to in the studio as the “honeycomb piece” (DSS 160).

In February, Judd hires Peter Ballantine, a former Whitney Independent Study Program student, to begin renovation work on the first floor of 101 Spring Street. Ballantine will become the primary fabricator of Judd’s plywood works.

Judd moves his studio from the second floor of East Nineteenth Street to 101 Spring Street on January 27.

In early March, Judd and Finch meet Harvey Shapiro, a local political activist, editor of The Public Life, and organizer of Citizens for Local Democracy. Both Judd and Finch join the advisory committee of the organization, where they eventually meet other committee members, among them Hannah Arendt and Noam Chomsky. Finch becomes the director of the Lower Manhattan Citizens for Local Democracy, a subcommittee of the organization.

Judd and Finch learn from an article in The Village Voice of Robert Moses’s plan for the Lower Manhattan Expressway, designed as early as 1941 to link the Williamsburg Bridge to the Holland Tunnel with a multilane highway that would cut across Lower Manhattan just south of 101 Spring Street. The project would require razing a large swath of neighborhoods and cast-iron buildings. In April, Judd and Finch cofound Artists Against the Expressway, of which Finch becomes the chairperson.

In April, Judd’s essay “Complaints: Part I” is published in Studio International. Judd protests the state of art criticism in general, while citing the narrowness and slipshod thinking of art critics Clement Greenberg, Michael Fried, and their followers.

Judd’s work is exhibited for the first time in Japan: a cadmium red floor piece (DSS 138) is shown in Contemporary Art: Dialogue Between the East and the West at the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo.

Judd’s first large wraparound stack (DSS 187), each unit having green plexiglass on front and sides, is completed on June 16 by Bernstein Brothers.

On June 19, Barnett Newman, Lower East Side activist Ernesto Martinez, and others speak at a meeting of two hundred and fifty people at the Whitney Museum of American Art organized by Artists Against the Expressway. As a result of community outcry, the proposal is rejected by Mayor John Lindsay in July.

Judd, Finch, and their son Flavin move to 101 Spring Street. The family sleeps on the fifth floor and cooks on the fourth; the lower floors continue to undergo renovation and are used for storage. Peter Ballantine builds a low platform bed in walnut to Judd’s specifications. This is one of Judd’s earliest pieces of furniture. Ballantine also begins construction of a sleeping loft on the fifth floor, a project that evolves over time. The first floor is used as a studio following the removal of debris.

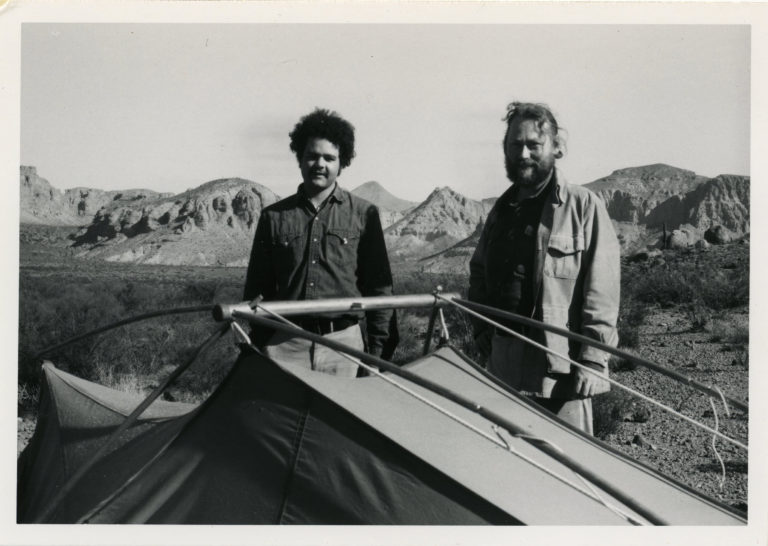

From August 13 through September 30, Judd travels to Tucson to visit his sister and parents and is later joined by Finch and Flavin. The family travels on to Mexico, Los Angeles, and back to New York. Judd later recalls, “We drove down the gulf coast of Baja California, which is excessively perfect in its lack of vegetation, inland at Bahía San Luis Gonzaga to the Pacific. . . . we stayed a month in El Rosario with Anita and Heraclio Espinoza, whose place was famous as a base camp for botanists and paleontologists. Each of the two following summers we stayed a month in El Rosario and a month camped out fifty miles inland on Rancho El Metate, a Spanish grant to the Espinozas.”

Judd writes the essay “Aspects of Flavin’s Work” for the Dan Flavin retrospective Fluorescent Lights, Etc. from Dan Flavin at the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, curated by Brydon Smith. Judd writes, “Three main aspects of Flavin’s work are the fluorescent tubes as the source of light, the light diffused throughout the surrounding space or cast upon nearby surfaces, and the arrangement together or placement upon surfaces of the fixtures and tubes. The lit tubes are intense and very definite. They are very much a particular visible state, a phenomenon. The singleness of isolation of phenomena is new to art and highly interesting.”

1969 Exhibition Summary

Judd’s work is in twenty-seven group exhibitions including New York Painting and Sculpture: 1940–1970, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, and five solo gallery exhibitions in New York, Los Angeles, Zürich, Paris, and Cologne.

Judd has his first major European retrospective at the Stedelijk Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven. He exhibits six floor works (DSS 83, DSS 119, DSS 129, DSS 156, DSS 180, and DSS 207) and six wall works (DSS 175, DSS 193, DSS 200, DSS 201, DSS 204, and DSS 206). The exhibition, curated by Jean Leering, travels to Museum Folkwang, Essen; Kunstverein Hannover; and Whitechapel Art Gallery, London.

Judd exhibits three stainless steel and plexiglass core works (DSS 128, DSS 144, and DSS 145) in American Painting and Sculpture 69th Annual Exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago. He receives the exhibition’s Laura Slobe Memorial Award of $1,000. A core work is a single-unit floor work comprised of transparent acrylic sheets on the top and long sides; the “core” space is created by an inset metal tube with flanges at both ends; the top plane and long sides are composed of transparent plexiglass.

In February and March, Judd delivers lectures at Cranbrook Academy of Art, Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, and Columbia University, New York.

A double solo exhibition of Judd’s work runs concurrently at Leo Castelli Gallery, 4 East Seventy-Seventh Street, and the Castelli Warehouse, 103 West 108th Street, New York. One work consisting of fifteen full and three partial sheets of hot-dipped galvanized iron placed perpendicular to the floor and eight inches off three of the gallery walls (DSS 221) is a radical departure from Judd’s previous work.

In early summer, Judd, Finch, and Flavin return to Baja California, camping near an arroyo. Judd will later recount, “In relation to a slight slope to the arroyo, I worked out a large piece for the land of Joseph Pulitzer in St. Louis. It’s a rectangle of two concentric walls of stainless steel, the outer one level and the inner one parallel to the slope of the land. Since this is related to the land on which it is placed it is a reasonable asymmetry. A month of camping in the sun leads to the idea of a small house.”

Barnett Newman dies on July 4, while Judd, Finch, and Flavin are staying with Larry and Glo Bell in Los Angeles. In a later interview with Michael Blackwood, Judd reflects, “I met him in ’64. I liked him a great deal; he was a good friend. He was a great painter and a smart man. I was very upset by his dying.”

Daughter Rainer Yingling Judd is born on August 11 in New York. Her namesake is friend Yvonne Rainer, and her middle name recognizes a Swedish ancestor on Judd’s maternal side.

Artist David Novros creates a fresco on the second floor of 101 Spring Street; it is the first permanent installation in the building. He later notes, “Judd was using that space as his laboratory to center on the belief that the placement of a work of art was critical to its understanding. He was thinking of the various paintings and sculptures of the building as ‘permanent installation.’ It worked out well for both of us, because it suits my concept of how a work of art could exist in an architectural space, what I’d call ‘painting-in-place.’”

John Chamberlain permanently places his large wall relief Mr. Press on the fifth floor of 101 Spring Street.

In “The Artist and Politics: A Symposium,” published in the September issue of Artforum, Judd warns, “If you don’t act, someone else will decide everything.” He continues, “Possibly the time will come when everyone will spend a day a week or more on public matters. It can be disagreeable but it’s a necessity. Most people seem to think that their representatives are elected to think for them, decide things, rather than represent decisions.”

Dan Flavin installs an untitled barrier piece on the fifth floor of 101 Spring Street using the same colors and a similar configuration to an earlier work titled an artificial barrier of blue, red and blue fluorescent light (to Flavin Starbuck Judd).

1970 Exhibition Summary

Judd has his first major European retrospective, Don Judd, Stedelijk Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven, curated by Jean Leering (subsequently traveling to Essen, Hannover, and London), and a double solo exhibition on view concurrently at two Leo Castelli Gallery locations in New York. In addition to four other solo gallery exhibitions, Judd has work included in twenty-three group exhibitions at venues including the Art Institute of Chicago, San Francisco Museum of Art, and the World’s Fair, Osaka.

In January, Judd writes about local politics for the first time, advocating for citizen decision-making and cautioning against the destabilizing power of centralized government institutions in the Newspaper of Lower Manhattan Township. Further statements are published in the April 3 and May 22 issues.

In February, Judd completes his first outdoor work (DSS 241) for the contemporary art collection of newsman Joseph Pulitzer Jr. in St. Louis. The work, in stainless steel, has an outer rectangle with a level top edge and an inner rectangle that follows the slope of the land.

Judd participates in an exhibition at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum titled Guggenheim International Exhibition 1971. The show focuses on the work of twenty-one emerging artists, including Carl Andre, Dan Flavin, Richard Long, Robert Morris, Richard Serra, and Lawrence Weiner. Judd creates a site-specific piece (DSS 242) consisting of two concentric rings of hot-rolled steel. The outer circle is level, while the inner circle follows the incline of the ramp.

Judd makes a pair of oval sinks with Bernstein Brothers for the fifth-floor dressing rooms at 101 Spring Street. “These were designed directly as sinks,” he would later write, “they were not a conversion; I didn’t confuse them with art.”

The retrospective Don Judd, at the Pasadena Art Museum in California (May 11–July 4), is curated and organized by art writer John Coplans with the involvement of museum director William C. Agee and art historian Barbara Haskell. Judd exhibits eleven floor works and twenty-six wall works, including the “honeycomb” piece previously exhibited at Leo Castelli Gallery; Judd expands the work to fit the museum’s particular space.

In May, Dudley Del Balso and Roberta Smith begin research for a Donald Judd catalogue raisonné to be published by the National Gallery of Canada in conjunction with Judd’s upcoming retrospective exhibition curated by Brydon Smith in 1975. Roberta Smith works part-time until January 1974, while Del Balso continues to work for Judd until 1984.

Judd’s first outdoor work in concrete (DSS 259) is completed for the collection of architect Philip Johnson in New Canaan, Connecticut. The work is a circle twenty-five feet in diameter; the outer circumference follows the slope of the land while the inner circumference remains level.

Judd creates an antiwar poster, Quotes for the War Resisters League, an electro-photographic print on yellow wove paper, with thirty-two statements pulled from the pages of The Public Life or by writers the paper frequently cites. The poster is printed and sold as both a signed limited edition to benefit the War Resisters League and a free, unsigned, unlimited edition.

Judd travels to Mexico in the summer and stays in El Rosario, Baja California. He makes drawings for a round house. Judd describes this unrealized project as “the first single house that I planned, single but around a courtyard and with enclosures and porches . . . for a round valley in the canyon of Arroyo Grande, where two canyons joined descending from Cerro El Matomi.”

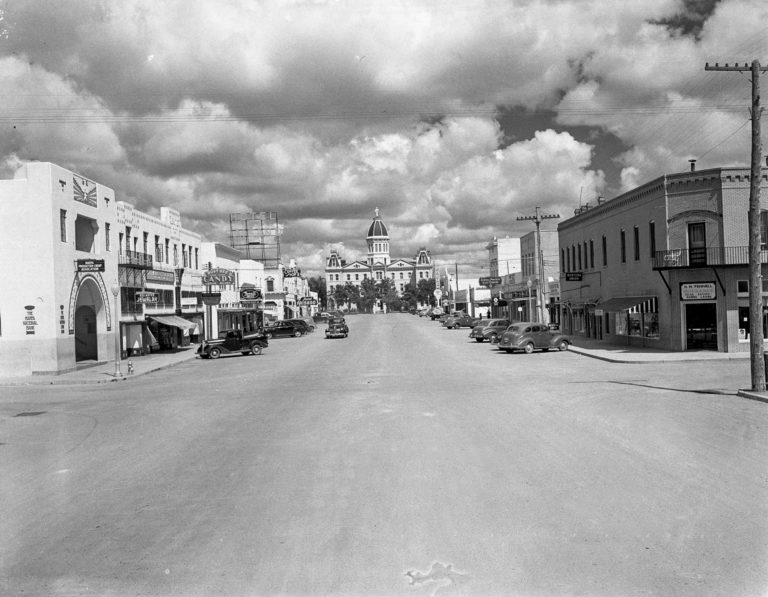

Under pressure to take advantage of Pasadena Art Museum director William C. Agee’s generosity in offering to ship the large-scale “honeycomb” piece anywhere within a year, Judd travels to Texas. “Looking at maps, I saw and remembered that Southwest Texas wasn’t crowded,” he later recounts. “I flew to El Paso in November 1971 and drove to the area of the Big Bend of the Rio Grande in the Trans-Pecos. In addition to my developing idea of installations and my need for a place in the Southwest, both due in part to the harsh and glib situation within art in New York and to the unpleasantness of the city, I had set a deadline for finding a place.” Judd chooses Marfa, Texas, because “it was the best looking and most practical.” He rents a little house known as the de Anda House.

Judd rents one of two abandoned airplane hangars that he will eventually purchase. These become the east and west buildings at the Block, which he will later name La Mansana de Chinati: “It was originally two warehouses that had been airplane hangars that were moved by the US Army in the ’30s from an old airfield.”

1971 Exhibition Summary

A comprehensive retrospective of Judd’s work titled Don Judd is curated by John Coplans with museum director William C. Agee and art historian Barbara Haskell for the Pasadena Art Museum. Judd’s work is included in twenty group shows, three at major museums in Denmark, Belgium, and The Netherlands.

In January, Judd returns to Marfa, accompanied by his son Flavin and studio assistant Jamie Dearing. They bring a truckload of art, store it in the de Anda House, and then depart to Baja California.

In May, Judd shows in a two-person exhibition with Richard Serra at Leo Castelli Gallery, 420 West Broadway, New York. Judd exhibits a five-unit plywood piece (DSS 265) placed in a row against the gallery wall. Each box is based on parallelepipedon construction, each with open front and back. When the same five units are later installed at 101 Spring Street at the length of sixty feet, they are considered to be a unique site-specific work (DSS 323). For DSS 323, the space in which the objects are placed define the piece itself.

Judd will continue to make objects in plywood, painted and unpainted, throughout his life. The use of plywood allows Judd to make large-scale works because it is more cost-effective than other traditional materials used for making three-dimensional objects. In addition, he appreciates plywood for its innate qualities such as color and grain.

Judd joins in signing a declaration of opposition against Documenta 5, stating the exhibition “illustrat[es] misguided sociological principles and categories of art history.” Composed by Robert Morris, the letter is published in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung on May 12, 1972. Nevertheless, the exhibition is held in Kassel. Of those who sign the letter of protest, only Judd, Robert Morris, Carl Andre, and Fred Sandback withdraw their works.

Barbara Rose interviews Judd in the summer for the documentary film American Art in the 1960s. Judd explains that the influence of Jackson Pollock, Barnett Newman, Mark Rothko, and so forth was limited to four assumptions: “That you have a single unit, but that the painting, in their case, is more or less one thing. That any color is a primary consideration. That whatever form there is—configuration, whatever it is—is a primary thing. And none of these things is subordinate to anything you can think of, like other images, or the depiction of realistic things, or things like that, and scale.”

The group show Furniture by Artists is held at Leo Castelli Gallery. Judd designs a coffee table, meant to be made in an edition of one hundred. He later writes, “Someone asked me to design a coffee table. I thought that a work of mine which was essentially a rectangular volume with the upper surface recessed could be altered. This debased the work and produced a bad table, which I later threw away.” This is the first time Judd’s furniture is shown in a gallery context.

Judd exhibits his first recessed-front stack (DSS 270) at Greenberg Gallery, St. Louis. The piece has ten units made in stainless steel with cadmium red light–enameled front planes set back within the outer frame.

1972 Exhibition Summary

Judd has three solo gallery exhibitions in Cologne, Paris, and St. Louis, as well as work in twenty-one group exhibitions throughout Europe and the United States.

A solo exhibition, Don Judd, is presented at Leo Castelli Gallery, 420 West Broadway, New York.

In February, Judd and his family stay in Marfa. He rents a house that he describes as being “on a knoll east of town in a poor neighborhood called Sal Si Puedes. The house and about seventeen acres belonged to a family named Lujan, so that it was called the Lujan House. The house was small with four rooms, each about 11 by 11 feet, one the kitchen, one eating, one a bedroom for the children, one for the grown-ups. The bathroom was outside about fifty feet away. There had been a wooden windmill. Its concrete storage tank still existed and could be filled for swimming. You could see fifty miles all around.”

In a letter dated February 28, 1973, Judd writes to John Lindsay, mayor of New York, advocating for the creation of a cast-iron historic district in SoHo. Six months later, 101 Spring Street is designated as a landmark in the newly formed SoHo Cast Iron Historic District.

Arts Magazine publishes Judd’s “Complaints: Part II” in March. Expanding on his 1969 essay “Complaints: Part I,” in which he wrote “about the incompetence of art criticism and the attempts of various persons to stop thinking,” he states, “That situation hasn’t changed. The other great failure is that of the museums and of public support generally.”

Judd is interviewed by artist Richard Stankiewicz for Four Sculptors, a film directed by Carl Howard. Other sculptors interviewed are Louise Nevelson, George Rickey, and George Segal.

On October 18 and 19, from Marfa, Judd arranges for a loan from Chemical Bank to purchase two former World War I airplane hangars from Bascomb and Harold Webb for $40,000. These will become known as the east and west buildings at the Block, and the east building will accommodate the “honeycomb” piece from Judd’s 1971 Pasadena exhibition.

Judd travels to Italy for the first time for a major international group exhibition. “In 1973,” Judd later recalls, “I went to Rome to make a large work of plywood for a very large exhibition called Contemporanea, directed by Achille Bonito Oliva, of all people, to be installed in, to dignify, to justify, to recoup a new uselessness, a new garage beneath part of the Villa Borghese gardens, more dirty work for art.” Contemporanea is on view November 30, 1973, through March 17, 1974. Judd travels to Arezzo, Florence, and then to Varese, where he visits collector Giuseppe Panza’s villa. Panza subsequently purchases several large-scale Judd works through Leo Castelli Gallery.

A solo exhibition, Don Judd, at Galerie Heiner Friedrich in Munich, from November through December, includes eighteen individual floor works in galvanized iron (DSS 247–257, DSS 298–304). It is accompanied by a small catalogue, Don Judd 18 Skulpteren 1972–1973. The exhibition then travels to Annemarie Verna Galerie, Zürich. This is the first of eight solo exhibitions at Annemarie Verna Galerie during Judd’s lifetime, marking the beginning of a lifelong personal and professional relationship with Annemarie and Gianfranco Verna.

Judd and sculptor David Rabinowitch meet for the first time. Rabinowitch later remarks, “I was living on Mercer Street, across the street from here [101 Spring Street]. I got a call. It was, I think, in 1973. Don invited me for supper. At first, I thought it was kind of a joke, because I knew of Don, but he said that he was interested in buying my work that he’d seen at Yale. There was a group show there. I think I came over here to supper the same week.” Judd later acquired three works from David Rabinowitch and placed them at the Chinati Foundation.

1973 Exhibition Summary

Judd participates in twenty-one group exhibitions, including 1973 Biennial of Contemporary American Painting and Sculpture, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, and American Painters Through Two Decades from the Museum Collection, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York. There are seven solo exhibitions in New York, Minneapolis, Rome, Milan, Turin, Munich, and Zürich.

In January, Dudley Del Balso and Roberta Smith give a draft of the Judd catalogue raisonné to Brydon Smith, curator of contemporary art at the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa, for fact-checking. As a majority of Judd’s works are untitled, the catalogue raisonné introduces a numerical identification system prefixed by “DSS,” the first initials of the catalogue editors’ surnames—Del Balso, Smith, and Smith—followed by the catalogue number for each piece.

Judd begins to install work in the east building at the Block. “The buildings and the land in town were in bad shape,” he later recalls. “I concentrated on the east building and began to install work there in 1974. The installation of the south room took about a year and was the basis for the room of old pieces in the exhibition I had in 1975 at the National Gallery of Canada.”

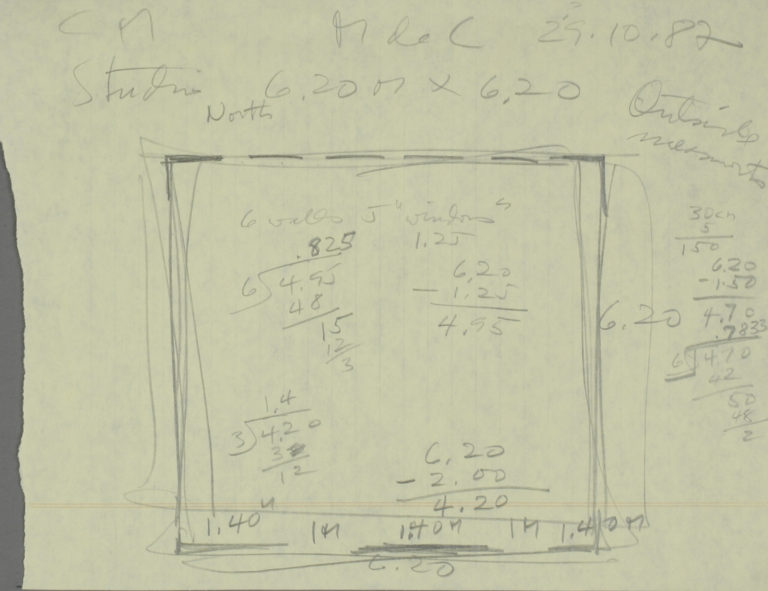

Judd travels to a solo exhibition, Don Judd, at Lisson Gallery, London, featuring two site-related works in plywood (DSS 313 and DSS 314) that are determined by room dimensions. Although the works are dismantled after the exhibition, Judd states that they can be remade at other locations with dimensions determined by the space.

Judd travels to Australia for the first time—from February 12 to March 10—to execute the commission of a triangular outdoor work in concrete for the Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide, in conjunction with the traveling exhibition Some Recent American Art, organized by The Museum of Modern Art, New York. He returns to Australia on May 19, during which time he is interviewed by curator Ian North for the archives of the Art Gallery of South Australia on May 30. “Well, I thought I was going to have to deal with a flat site, because John Baily said it was flat. The concrete pieces were sort of developed in terms of a slope, so I really didn’t have a piece for a flat site,” he tells North. “Somewhere in the back of my mind was an idea to make it triangular. . . . This is the first triangular piece of any kind, little or big. Everything got abruptly reversed when John met me at the airport and realized after he got home that it [the site] was sloped. So then I could have gone back to the—usually an idea has a number of possibilities. [Philip] Johnson’s piece, where the slope, the bevel, was on the outside—the bevel could be on the inside, so in a way you have two pieces there; the other circle could have been used here. But again, that’s pretty predictable. I know it would have been a nice piece. But also now that I’ve seen the first thing, it’s a sure thing, and I’m inclined to—it’s more fun to take a chance on it.”

Judd participates in The Chile Emergency Exhibition, organized by the U.S. Committee for Justice to Latin American Political Prisoners, held at 383 West Broadway in New York.

On July 23, Judd purchases a two-story building adjacent to the airplane hangars at the Block. This building had been used as the quartermaster’s office for Fort D. A. Russell, a former cavalry post and later World War II prisoner of war camp located on the south edge of Marfa. “Within the city block, in addition to the two large buildings, there is a smaller two-story building, the office of the Quartermaster Corps, with two children’s rooms and the necessary domesticity,” Judd later writes. “I’ve built two small adobe buildings nearby, symmetrically placed, one a bath and the other an office. There is a large vegetable garden. Next to it there is a structure, part green/dog/chicken house. Next to the children’s building is a pergola and a pool, both built by Celedonio Mediano, who has built everything. His brother, Alfredo Mediano, takes care of the art, a serious matter not sufficiently so regarded by those reputedly interested in art.”

Judd authorizes the fabrication of a large, site-related, U-shaped wall work in plywood by students for the Portland Center for the Visual Arts. The work is dismantled immediately after the exhibition, and the wood is returned to the lumber company that supplied it.

1974 Exhibition Summary

Judd has six solo exhibitions, four of which take place in Europe: London, Amsterdam, Cologne, and Innsbruck. His work is included in twenty-four group exhibitions, including Some Recent American Art, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne (traveling to the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney; Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide; Australian Art Gallery, Perth; and City of Auckland Art Gallery). Judd executes the commission of a triangular outdoor work in concrete for the Art Gallery of South Australia in conjunction with the exhibition.

“Interview with Lucy R. Lippard and William C. Agee,” in Donald Judd Interviews, 279.

Judd, “Specific Objects” (1965), in Donald Judd Writings, 141.

James Fitzsimmons, letter to Donald Judd, January 26, 1965, in Donald Judd: Complete Writings 1959–1975, 170.

Judd, “Lee Bontecou” (1965), in Donald Judd Writings, 163.

James Fitzsimmons, letter to Donald Judd, April 21, 1965, in Donald Judd: Complete Writings 1959–1975, 171.

“Interview with Bruce Glaser and Lucy R. Lippard” (December 8, 1965), in Donald Judd Interviews, 88.

Hilton Kramer, “Art Constructed to Donald Judd’s Specifications: Depersonalized Works Found Discontenting,” The New York Times, February 19, 1966, 23.

“‘The New Sculpture,’ symposium with Kynaston McShine (moderator), Mark di Suvero, and Barbara Rose” (May 2, 1966), in Donald Judd Interviews, 94.

“Interview with Ian North” (May 30, 1974), in Donald Judd Interviews, 441.

See chapter 4 of Matthew Israel, Kill for Peace: American Artists against the Vietnam War (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2013).

Judd, “Jackson Pollock” (1967), in Donald Judd Writings, 190.

“Artists’ symposium for 7 for 67, with Emily Rauh (moderator), Mark di Suvero, and Ernest Trova” (October 1, 1967), in Donald Judd Interviews, 202.

Joanna Eagle, “Artists as Collectors: Eleven Members of This Unique Breed Describe an Involvement That Shuttles Between Calculation and Passion,” Art in America, November/December 1967, 59.

“Interview with Barbara Rose and Frank Stella” (1966–67), in Donald Judd Interviews, 149.

Dudley Del Balso, email to Caitlin Murray, January 8, 2019.

“Donald Judd,” John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation.

Judd, “Marfa, Texas,” in Donald Judd Writings, 425.

Judd, “Marfa, Texas,” in Donald Judd Writings, 426.

Judd, “Aspects of Flavin’s Work” (1969), in Donald Judd Writings, 211.

Judd, “Marfa, Texas,” in Donald Judd Writings, 426.

“Interview with Michael Blackwood for the film Masters of Modern Sculpture Part III” (September 1975), in Donald Judd Interviews, 477–78.

“In Conversation: David Novros with Phong Bui,” The Brooklyn Rail, June 7, 2008.

Judd, “The Artist and Politics: A Symposium” (1970), in Donald Judd Writings, 216.

See Judd, “General Statement,” “Revenue Sharing,” and “Greater Westbeth” (1971), in Donald Judd Writings, 220, 226, and 232, respectively.

Judd, “On Furniture” (1986), in Donald Judd Writings, 452.

Judd, “Westfälischer Kunstverein,” in Donald Judd: Architektur (Munster: Westfälischer Kunstverein, 1989), 25.

Judd, “Marfa, Texas,” in Donald Judd Writings, 427.

“Interview with Regina Wyrwoll for the television documentary Bauhaus, Texas” (October 4–5, 1993), in Donald Judd Interviews, 858.

“documenta 5,” Documenta.

“Interview with Barbara Rose for the film American Art in the 1960s” (Summer 1972), in Donald Judd Interviews, 397.

Judd, “On Furniture,” in Donald Judd Writings, 451.

Judd, “Westfälischer Kunstverein,” in Donald Judd: Architektur, 29.

Judd, “Complaints: Part II” (1973), in Donald Judd Writings, 239.

Donald Judd, “Una stanza per Panza” (1990), in Donald Judd Writings, 648.

Interview with David Rabinowitch, September 9, 2006. Judd Foundation Oral History Project, Judd Foundation Archives, Marfa, Texas.

Judd, “Marfa, Texas,” in Donald Judd Writings, 428.

“Interview with Ian North,” in Donald Judd Interviews, 438.

“Interview with Ian North,” in Donald Judd Interviews, 440.

Judd, “Marfa, Texas,” in Donald Judd Writings, 430.