After the perimeter wall at the Block is completed, an inner U-shaped interior adobe wall is built. Later referring to the exterior and the interior U-shaped walls, Judd writes, “The two walls and two areas, one sloped and the other level, make a work, I suppose both art and architecture, although usually the distinction is important.”

Judd leaves Leo Castelli Gallery to work with Paula Cooper Gallery as his primary New York representative.

Judd is interviewed by journalist Pilar Viladas for the magazine Progressive Architecture. The resulting conversation provides an in-depth look at the progression of Judd’s property ownership and architectural work in Marfa.

Judd writes the essay “Marfa, Texas,” describing the development of his activities as it relates to art and architecture in Marfa. It is published in the April issue of House & Garden. “This place [La Mansana de Chinati/The Block] is primarily for the installation of art, necessarily for whatever architecture of my own that can be included in every situation, for work, and altogether for my idea of living,” he declares. “As I said, the main purpose of the place in Marfa is the serious and permanent installation of art.”

Judd is interviewed by painter Russell Connor for the television documentary American Art ’85: A View from the Whitney on the occasion of his participation in the 1985 Biennial Exhibition, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York.

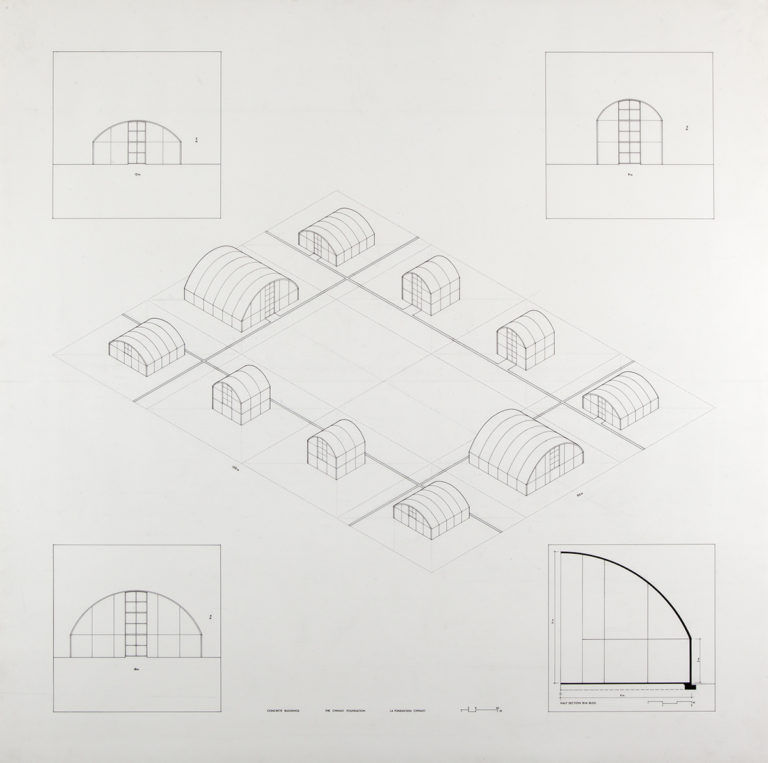

Judd produces the first drawings for ten proposed buildings at the Chinati Foundation, two of which will be partially constructed; eight remain unrealized due to engineering challenges.

1985 Exhibition Summary

Judd has six solo shows, in Zürich, Naples, Frankfurt am Main, Chicago, Houston, and New York, and work in thirty-six group exhibitions throughout the United States and Europe, including in Marseille, Bordeaux, London, Madrid, Mexico City, Los Angeles, and New York. In addition, he is a panelist at the Detroit Institute of the Arts and at an architecture symposium at Harvard University.

Judd begins work on Eichholteren, a former restaurant and hotel built in 1943 in Küssnacht am Rigi, Switzerland. The building was purchased by advertising executive Paul Gredinger. An agreement between Gredinger and Judd specifies their individual responsibilities: Gredinger financial, Judd creative, to include artwork, furniture, and architectural design. Collaborating with Zürich-based architect Adrian Jolles, Judd renovates it to serve as a home and studio. Eichholteren is remodeled step by step from 1989 to 1993, with Judd making a number of architectural interventions, at least one of which relates to 101 Spring Street: “On the fourth floor [of 101 Spring Street] there is a wooden floor and a wooden ceiling that make two identical, parallel planes. The ceilings were very low, so I used the same idea in the building there [Eichholteren].”

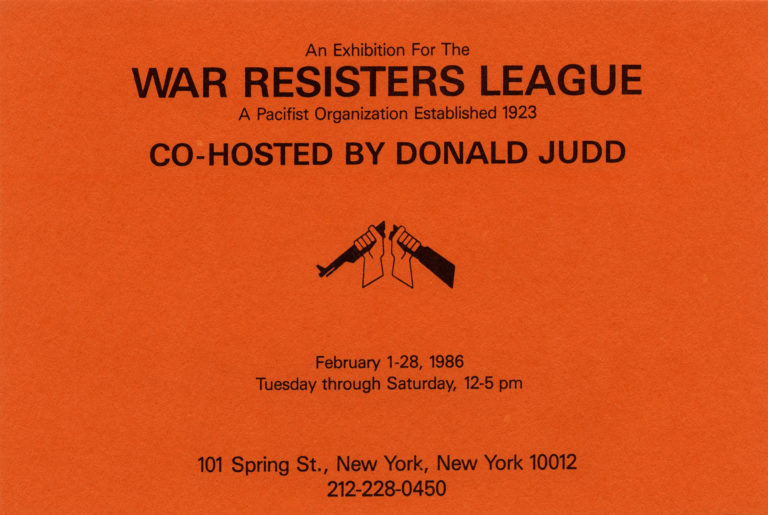

Judd cocurates a War Resisters League benefit exhibition at 101 Spring Street. It features works by Carl Andre, Frank Stella, and Meg Webster, among others. Andre installs Manifest Destiny, made of eight stacked bricks stamped with the word “EMPIRE,” in the southwest corner of the ground floor. Judd acquires the work. This is Judd’s third participation in a War Resisters League exhibition and the second that he hosts.

Judd exhibits a large-scale oval floor work in galvanized iron at In Honor of John Chamberlain at Xavier Fourcade in New York.

Judd attends the opening of a group exhibition in which his work appears, Qu’est-ce que la sculpture moderne?, at the Musée National d’Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris. During this trip, Judd makes preparations for a series of exhibitions in Paris scheduled for the following year.

Judd begins working with a new Swiss fabricator, Menziken AG, that specializes in anodized aluminum. After making an initial six pieces successfully with the factory, he begins to use the metric system to conceive all works made by this fabricator. He continues to work with Menziken for the rest of his life.

In August, Judd and Dia Art Foundation sign an agreement transferring ownership of artwork and property from Dia to the Chinati Foundation. Judd’s installation of the 100 works in mill aluminum is completed, ending a four-year process.

In November, Judd begins working on an architectural proposal for a site in Cleveland. He will later write, “Through Coosje van Bruggen and Claes Oldenburg, Peter Eisenman and Frank Gehry asked me to participate, along with the former, Richard Serra, and Carl Andre, in a large complex for an insurance company in Cleveland, Ohio, mainly by making a work of art but also by making suggestions. In thinking a little, I soon thought a lot, and became enthusiastic and asked Lauretta Vinciarelli, an architect and a professor at Columbia University, and Claude Armstrong, an architect in New York City, and Donna Cohen to visit Cleveland and also think. This produced some sketches, plans, and a model. The site, on again, off again, as is the project, is very complex.” The proposal is rejected.

Judd creates a work in folded stainless steel and black plexiglass rods to benefit the New Museum, New York, in an edition of forty with ten artist’s proofs; it is published by Brooke Alexander.

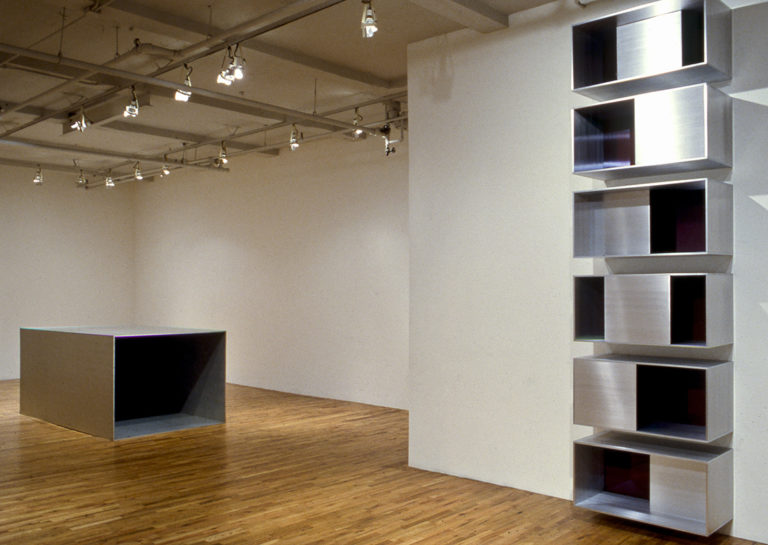

Judd has his first solo exhibition, Donald Judd, at Paula Cooper Gallery. The show includes seven works, including his longest multicolored work, fabricated by Lehni AG; two Douglas fir plywood pieces fabricated by Peter Ballantine in New York; and several pieces, including a Cor-ten steel wall work, fabricated by Lippincott, Inc. in North Haven, Connecticut.

Image: Installation view, Donald Judd, Paula Cooper Gallery, October 4–November 1, 1986. Photo James Dee. Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery.

Judd writes “On Furniture” for Möbel Furniture, a small catalogue of his metal furniture fabricated by Lehni AG. “The art of a chair is not its resemblance to art, but is partly its reasonableness, usefulness, and scale as a chair,” he argues. “These are proportion, which is visible reasonableness.”

Throughout 1986, Judd writes numerous notes on subjects as diverse as the decline of art and architecture, civilization, the history of art, and the color red. Describing this activity, he says, “Writing is a further attempt to maintain my work and control what happens to it, to maintain my integrity, my momentum, against others’ distortions.”

1986 Exhibition Summary

Judd has two solo exhibitions, at Paula Cooper Gallery, New York, and Waddington Galleries, London, and participates in forty-four group exhibitions, including shows in Madrid, Stockholm, Cologne, Munich, Paris, Schaffhausen, Eindhoven, Bremen, Høvikodden, Dunkirk, Krefeld, and London.

In January, Judd begins fabrication of multicolored works with Studer AG, Switzerland, and later moves fabrication to Lascaux Conservation Materials in Brooklyn. No longer working with Lehni AG, he begins furniture production at Janssen, a painted aluminum fabricator located in The Netherlands.

On January 6, Judd travels from Zürich to Moscow with his children, where they visit the Melnikov House. With a focus on regional history, Russian icons, and religious architecture, they travel to Suzdal, Yaroslavl, Rostov-the-Great, Novgorod, and Leningrad.

Judd has work in the exhibition A Century of Modern Sculpture: The Patsy and Raymond Nasher Collection at the Dallas Museum of Art. The show includes a progression with an aluminum tube and green anodized boxes. The exhibition travels to the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC.

Paul Cabon assists Judd with the installation of the exhibition Repères: Judd at Galerie Maeght Lelong, Paris. Cabon, a French professor of art history and design theory, interviews Judd around the same time. In response to Cabon’s question about the functions of his studio, Judd describes the evolution of his working studio at East Nineteenth Street to having work fabricated elsewhere and the studio becoming a place to sketch ideas and to think. He describes his current studio practice as “mostly, my work is done by me carrying a bunch of papers around and sitting around and thinking. . . . I sketch out the idea in a very loose way to the extent of what I need for myself, and then I go to the factory. Then the factory translates the idea into an engineering drawing with the requirements necessary for the worker to know what he’s doing.”

A major museum show curated by Rudi Fuchs, Donald Judd: Sculptures 1965–1987, opens at the Stedelijk Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven. The exhibition includes forty-six works and travels to the Stadtische Kunsthalle, Düsseldorf; Musee d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris; Fundació Joan Miró, Barcelona; and Castello di Rivoli, Turin.

Judd is recognized for his work by the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in Maine, receiving the Skowhegan Medal for Sculpture on April 28 in New York.

Judd attends a ceremony in New York to receive the Brandeis University Medal for Sculpture on April 29.

Judd includes work in the second iteration of Skulptur Projekte Münster, curated by Kasper König and Klaus Bußmann. The exhibition reviews historical and social narratives of the city of Münster, as well as referencing the original 1977 Skulptur Projekte Münster.

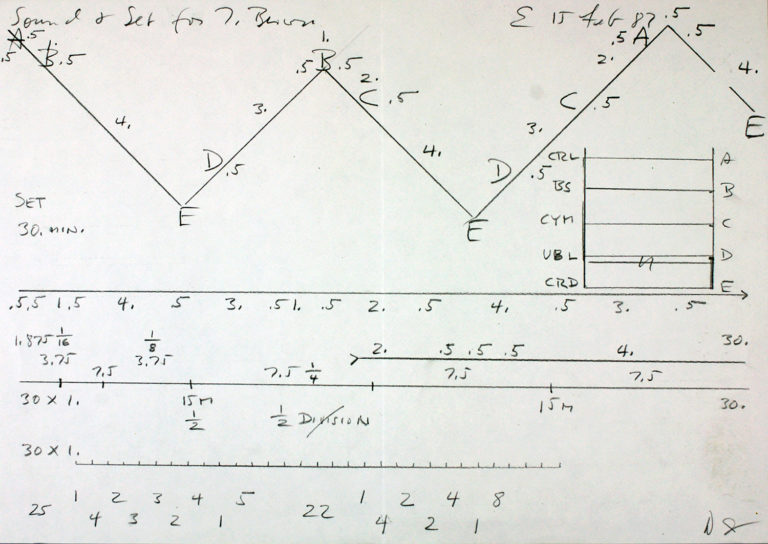

On July 10, Newark (Niweweorce), a performance by Trisha Brown Dance Company, premieres at the CNDC/Nouveau Theatre d’Angers, France. It is the second collaboration between Brown and Judd, who designs the visual, costume, and sound concepts; the latter is a series of bagpipe tones developed with musician Peter Zummo. The performance makes its U.S. premiere at the City Center New York on September 14.

Image: Donald Judd, drawing of set and sound design for Trisha Brown Dance Company’s Newark (Niweweorce), pencil on paper. Judd Foundation.

On October 10, Judd hosts the first open house at the Chinati Foundation (the property and artwork have now been fully transferred from Dia Art Foundation). The open house is celebrated with a temporary exhibition of prints by Barnett Newman and Josef Albers, and drawings by Texas artist Robert Tiemann.

On October 24, Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen visit Marfa, and van Bruggen proposes that they create a sculpture for the Chinati Foundation. As Judd will later recount, “Claes says, ‘Looking for a way to respond to the landscape, history of the place, both past and present.’ He heard the story of Louie, the last horse, and measured the existing monument, more of a tombstone, which once had a circular epitaph painted on it, of which we have a photograph. Claes made drawings for Monument to the Last Horse. He notes, ‘Visit to ranch with Don, where I find a horseshoe. Nail picked up later on road behind barracks. Concept of placing adobe over a steel skeleton of horseshoe. Visit site at sunrise.’ They went back to New York and Claes made the first model, using the shoe and nail, at Lippincott.”

The Chinati Foundation/La Fundación Chinati, a catalogue on the new foundation with photographs by Rob C. Wilson, is published. In an included statement by Judd, he explains that the art installed at the foundation is meant to be permanent and seen in a space that is “suitable to it,” writing, “Somewhere, just as the platinum-iridium meter guarantees the tape measure, a strict measure must exist for the art of this time and place. Otherwise art is just show and monkey business.”

1987 Exhibition Summary

Judd has six solo gallery exhibitions: Donald Judd: Neue Skulpturen, Galerie Rolf Ricke, Cologne; Don Judd, Annemarie Verna Galerie, Zürich; Repères: Judd, Galerie Maeght Lelong, Paris; Donald Judd: New Work, Adair Margo Gallery, El Paso; Donald Judd, Lawrence Oliver Gallery, Philadelphia; and Painted Wall Sculptures, Margo Leavin Gallery, Los Angeles. A retrospective exhibition titled Donald Judd: Sculptures 1965–1987, Stedelijk Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven, subsequently travels to Stadtische Kunsthalle, Düsseldorf; Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris; Fundació Joan Miró, Barcelona; and Castello di Rivoli, Turin. There are thirty-nine group exhibitions, including his only exhibition in Scotland, Homage to Beuys, Fruitmarket Gallery, Edinburgh.

Judd meets artist Roni Horn in New York. “I saw an exhibition of her [Roni Horn’s] drawings around ten years ago, at Galerie Lelong in New York. I liked the drawings, and I bought a couple,” he will later tell an interviewer. “Then I went there one day and by chance she was there. And so on. That’s not exactly an accident. So I got to know Roni, and then I saw another show where she had three-dimensional work. By now I’ve seen a lot of her shows.” Judd and Horn remain friends for the rest of his life.

“Donald Judd’s View” is published in the February issue of Blueprint. Judd addresses questions about architecture, saying, “Form may not closely follow function but my axiom is that form should never violate the function. ‘Forms’ for their own sake, in spite of the function, are ridiculous.”

Donald Judd, Richard Long, Kristján Guðmundsson opens at The Living Art Museum, Reykjavík, on June 4; Judd travels to the Reykjavík Art Festival at the invitation of the museum. The exhibition is guest curated by Petur Arason.

Judd installs a 1988 work by Richard Long at the Chinati Foundation. The circular work is made from Icelandic lava rock.

At the beginning of the summer, Rob Weiner is hired as a studio assistant at 101 Spring Street. He will continue to work as a studio assistant until February 1994.

“Donald Judd – Veränderung in einem für gute Kunst gültigem Mass” (A Change in a Degree That Is Valid for Good Art) is published in Kunstforum International’s June/July issue. In the interview, Judd explains, “I purposely don’t work in groups and series and exhaust all logical possibilities, because some of them aren’t good, or are redundant. But who hasn’t produced works that don’t belong together? Ad Reinhardt made many good works, even if the black paintings all look the same or similar from the outside. To me, they aren’t alike, and I am convinced that Reinhardt also saw them like that.”

During the summer, Judd establishes and operates El Taller Chihuahuense, a metalworking shop, and hires Raul Hernandez, Lee Donaldson, and other local welders to make his work in Cor-ten steel. The shop is located in a former ice plant in Marfa.

Judd is asked to submit a proposal for a traffic circle in Belley, France. The unrealized proposal is for a series of concrete walls. A year later, Judd makes a similar design of concentric circles at his Las Casas ranch house at Ayala de Chinati.

Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen visit Marfa in August to work on Monument to the Last Horse at the Chinati Foundation. Judd will later recall, “The ninth of August 1988 they came back to Texas. . . . It was clear when the mock-up was outdoors that its size and scale were right. It was in a great deal of space.”

Roni Horn installs Things That Happen Again: For a Here and a There (1986–1991) at the Chinati Foundation.

An exhibition by Swiss painter Richard Paul Lohse, organized by Judd and Rudi Fuchs, opens at the Chinati Foundation in October. The exhibition travels to 101 Spring Street and then to the Gemeentemuseum Den Haag. In the catalogue, Judd writes, “In Lohse’s work there is the end of the European compositional tradition, a good end, and also there is the beginning of much that is still beginning to develop.”

The Centro de Arte Reina Sofía in Madrid mounts the exhibition Arte Minimal Colección Panza. It includes four unauthorized works made in plywood that were fabricated by Giuseppe Panza without the artist’s knowledge or consent. Judd vigorously objects.

Judd’s second major solo exhibition opens at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. The exhibition, curated by Barbara Haskell, travels to the Dallas Museum of Art in February. Among the works exhibited are a large-scale, three-unit concrete work; thirty units of a three-tiered wall piece made in Douglas fir plywood and various colors of plexiglass; and furniture designed by Judd.

Image: Installation view, Donald Judd, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, October 20–December 31, 1988. Photo Geoffrey Clements. Courtesy Whitney Museum of American Art.

1988 Exhibition Summary

Judd has six solo exhibitions, some of which are held in Vienna, Stockholm, New York, and Cologne, including a retrospective, Donald Judd, which originates at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York and travels to the Dallas Museum of Art in 1989. There are fifty-eight group exhibitions. He travels throughout Europe to oversee exhibition installations and spends an extended period of time in Iceland. Group exhibitions include Masters of Modern Sculpture, Contemporary Art Gallery, Seibu, Tokyo; Donald Judd, Richard Paul Lohse, Klaus Metting, Museo d’Arte Contemporanea, Castello di Rivoli, Turin; and Donald Judd, Richard Long, Kristján Guðmundsson, The Living Art Museum, Reykjavík.

On January 21 and 22, Judd participates in a workshop, along with John Chamberlain, Robert Irwin, Michael Graves, and Frank Gehry, among others, at the Frederick R. Weisman Art Foundation in Santa Monica, California. The workshop and subsequent publication are titled “The Relationship between Art and Architecture.”

In Dallas on February 23, Judd gives a whirlwind lecture of eighty slides in forty minutes covering his art and architecture. The lecture is in conjunction with his retrospective at the Dallas Museum of Art.

Judd joins the Board of Visitors of the McDonald Observatory, University of Texas, Austin, at the invitation of interim director Dr. Frank N. Bash. The observatory is located thirty miles north of Marfa. On February 25, after attending dinner with a group of university astronomers, Judd writes, “It’s curious that change is so fast technologically and so slow socially. The Whole Earth Telescope is mainly observing white dwarfs, so as to establish known behavior to estimate distances, and to search. They estimate the age of this galaxy from white dwarfs to be nine billion years.”

Donald Judd: Architektur, organized by curator Marianne Stockebrand, opens at the Westfälischer Kunstverein, Münster, where Stockebrand is the director. The exhibition primarily includes furniture and architectural drawings. The Kunsterverein concurrently publishes Donald Judd: Architektur, an exhibition catalogue printed in both German and English; it includes several of Judd’s writings on art and architecture. Stockebrand and Judd subsequently establish a personal and professional relationship.

Judd writes the essay “Ausstellungsleitungsstreit” for the Ludwig Museum exhibition Bilderstreit, on view at the Rheinhallen, Cologne. The article, which criticizes institutional exhibition practices, is not included in the catalogue but is published in the April/May issue of Kunstforum. Unhappy with the way his work is installed in Bilderstreit, Judd demands that his works be removed and that the lenders of his works rescind their loan agreements. All comply.

In June, Judd buys sections of land in Texas that include Las Casas. Located approximately seven miles from the U.S.–Mexico border, Las Casas includes three buildings that he renovates for use as a home, studio, and bunkhouse. Outdoors, he adds a series of concentric rock walls around an existing water tank, a circular rock wall for a garden, and a guesthouse. Judd also begins work on three stables that are to be used as a tack room, horse stable, and chicken coop adjacent to an existing black lava rock corral; the rock walls of these structures are built and still extant, while the roofs are planned but never completed.

The Staatliche Kunsthalle Baden-Baden presents Donald Judd, a solo exhibition. The show includes a group of twelve unique floor works in anodized aluminum and plexiglass made by Menziken AG.

The Innovators/Entering the Sculpture, Ace Contemporary Exhibitions, Los Angeles, is organized by Douglas Chrismas, Giuseppe Panza, and Leo Castelli. The show includes an unauthorized galvanized iron wall work that is disavowed by Judd. “I insisted that the work be destroyed immediately,” Judd will later write. “It has already been up for two weeks or so, incorrect in size and detail, for example two narrow panels forming on corner. A work that is not mine was shown as mine. This harms my work; this harms my reputation—you can be sued for this. Chrismas stalled but my staff was with me and we watched and implied legal action. He took it down and the plates are being sent to Texas as proof of destruction.”

On November 6, Judd purchases the former Marfa National Bank Building, which he refers to as the Architecture Studio. By December, Judd creates working spaces throughout the Architecture Studio, placing his own furniture—including bookshelves, a standing writing desk, chairs, and a bed—alongside pieces by Alvar Aalto, Marcel Breuer, Josef Hoffmann, Gerrit Rietveld, and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. Judd also installs paintings by Antonio Calderara, Larry Bell, Josef Albers, and Theo van Doesburg.

Judd purchases three buildings located west of the Architecture Studio from William and Barbara Morgenstern. They are referred to as the Gatehouse, the Cobb House, and the Whyte Building. The Gatehouse, the smallest structure, was formally a barbershop and a record shop.

1989 Exhibition Summary

Judd has nine solo exhibitions and oversees the installation of each. These include Donald Judd: Architektur, Westfälischer Kunstverein, Münster; Donald Judd, Gallery Yamaguchi, Osaka; and Donald Judd, Staatliche Kunsthalle Baden-Baden. In addition, there are forty-seven group shows including Agnes Martin and Donald Judd, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and National Print Exhibition: Twenty-Fifth Biennial, Projects & Portfolios, the Brooklyn Museum.

Judd joins four individuals, as well as El Paso and Hudspeth Counties, to protest the federal government’s attempt to construct a nuclear waste storage facility near Fort Hancock, approximately 140 miles from Judd’s ranch. A court injunction in 1991 prevents the Fort Hancock facility from moving forward.

On January 23, Judd purchases the Glascock Building in Marfa from Genevieve Prieto Bassham and Albert Bassham. Designating it the Architecture Office, he installs the ground floor with his plywood tables, architectural models, and blueprints. The second floor is installed with John Chamberlain reliefs from 1964 and Aalto furniture. Judd has the text “A N and J GRACE, F I YINGLING, C, R C, and D C JUDD CABINETMAKERS” and “CLARENCE JUDD, ARCHITECTURE” painted on the west-facing storefront window. According to Judd, “The signs are to sort of establish a little dignity among the cabinet-makers in my family. They were pretty much farmers and woodworkers in Missouri. . . . My grandfather [Clarence Judd]—he built houses in Missouri, I didn’t want to name an architectural firm after myself, because I don’t have the legal certification, and I didn’t really want to get sued by the AIA [American Institute of Architects].”

On February 1, Judd participates in a seminar series discussion, “Gespräche mit Künstlern” (Talking to Artists), organized by Angeli Janhsen at the Ruhr-Universität Bochum, Germany. Judd later asks Janhsen for a record of the discussion so that it can be included in the exhibition catalogue for Donald Judd at the Kunstverein St. Gallen, Switzerland.

Judd purchases a former Safeway grocery store in Marfa from Patricia Coleman, Jonnie Mae Fuller Senter, and Fred O. Senter III on March 1. He converts the six-thousand-square-foot building into the Art Studio, removing a dropped ceiling to expose the building’s structure and adding skylights to increase natural light. He installs long worktables, shelving, prototypes, material samples, and artworks. Previously his studio occupied the second library space at the Block, but as Judd notes in a 1993 interview, “When the library became too big, I bought the building in town for the Art Studio and put the other part of the library into the old studio space.” One part includes twentieth-century volumes arranged by subject matter; the other includes pre-twentieth-century volumes arranged by country.

Judd acquires the former Marfa Hotel, which he reconfigures into an administrative office. It is located a block away from the Art Studio, adjacent to the Architecture Office.

In May, Judd writes “Una stanza per Panza” in response to the purchase by the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum of several Judd works and unrealized illegitimate plans included in the Panza Collection. The essay is published in four parts in Kunst Intern, a German publication. English copies of the essay are distributed at the 1990 Venice Biennale. Central to Judd’s argument is the claim that his artwork cannot be made without his involvement and consent. In the essay, Judd also criticizes collectors who purchase art solely for investment purposes and galleries and museums for their cooperation in undermining the art situation in New York and elsewhere.

In July, Judd establishes a studio, which he calls Hafenstrasse, in Cologne, leasing and renovating a former brewery. A 1991, a five-unit floor piece in mill aluminum is installed in the studio.

Judd attends the opening of his solo show at Person’s and Lindell, a small gallery in Helsinki. While there, he visits the bentwood fabricator Artek, founded by Alvar Aalto, whose work he admires and collects.

Due to direct transport from the United States being impossible, Person’s and Lindell arrange for the shipment of several Judd floor works made in Douglas fir plywood from New York to Moscow via Helsinki. In Moscow, at the invitation of curator Olga Sviblova, Judd exhibits the plywood works at the Soviet Cultural Foundation. It is noted as one of the first exhibitions by an American contemporary artist in the Soviet Union. Judd attends the opening and travels through the Golden Ring area northeast of Moscow, taking particular note of the secular and religious architecture in Pereslavl, Rostov, Ivanovo, and Suzdal, among other cities in the region.

In September, Judd begins the production of wood-frame furniture, overseen by independent art consultant Hester van Royen, at Design Workshop in Yorkshire.

On September 7, after donating a work to the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF), Judd accepts an invitation from founding director Jim Marston to join the Texas Advisory Committee for EDF.

On October 20, Judd attends an antiwar demonstration in Times Square to protest the Persian Gulf Crisis and the U.S. involvement in the Gulf War. The rallies held on October 20 are the first demonstrations coordinated nationally since President Bush sent more than 200,000 soldiers on October 17 to protect Saudi Arabia against Kuwait.

1990 Exhibition Summary

Judd participates in thirty-nine group exhibitions and ten solo shows. To supervise installation of the solo exhibitions alone, Judd travels to Belgium, England, Greece, Switzerland, Japan, Russia, and Finland while spending time in Germany, New York, and Texas to maintain contact with fabricators and oversee continuing work in Marfa. Among the solo exhibitions, Donald Judd, Kunstverein St. Gallen, is a major show of new work and Donald Judd, Soviet Cultural Foundation, Moscow, organized by curator Olga Sviblova, is believed to be one of the first exhibitions of a contemporary American artist in the Soviet Union.

In January, Judd leaves Paula Cooper Gallery to work with Pace Gallery as his sole New York representative.

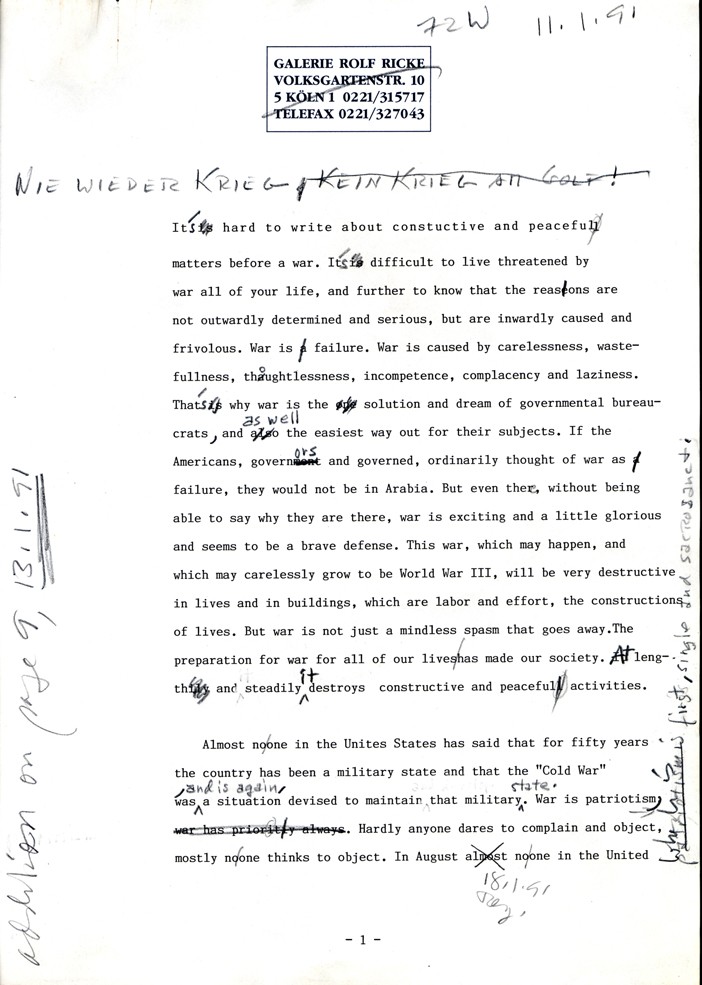

Operation Desert Storm occurs from January 17 to February 28. Against this backdrop, on January 20, Judd expresses his deep opposition to the war in an interview conducted by Ólafur Gíslason titled “War Destroys Culture.”

On February 9 and 10, Judd is interviewed by Georg Schölhammer for Der Standard. The resulting published interview is titled “Die Kunst, Der Krieg und Das Geld: Kunst-Heros Donald Judd über die Ohnmacht der Kunst und die Macht der Mächtigen” (Art, War, and Money: Art Hero Donald Judd on the Powerlessness of Art and the Power of the Powerful).

Donald Judd: Architektur, curated by Brigitte Huck, opens at the Österreichisches Museum für angewandte Kunst (MAK) in Vienna. Judd writes the antiwar essay “Nie Wieder Krieg” (Never Again War) for the exhibition catalogue and creates three political posters for the exhibition.

Judd meets artist Ilya Kabakov while traveling in Vienna in February. Judd invites Kabakov to visit the Chinati Foundation, where his work School No. 6 will open to the public two years later.

In March, Gianfranco Verna writes to Judd about the possibility of designing a fountain for the old town plaza in Steinbergasse, Winterthur, Switzerland. Commissioned in the same year by Stadt Winterthur, three Judd-designed fountains are eventually finished posthumously in 1995 and inaugurated on June 14, 1997. The fountains, all elliptical in form, are constructed with concrete and aggregate by a company based in Lenzburg.

In April, Judd directs his studio assistants to retrieve a group of his early paintings from his parents’ home in Excelsior Springs, Missouri, with the idea that all of his early work should remain together. Many of these works are subsequently permanently installed by Judd at the Cobb House. In the Whyte Building, he installs one relief, three large paintings, and reproductions of Rudolph Schindler furniture commissioned by Judd from woodworker Robert Nicolais.

On April 23, Donald Judd Furniture opens at the Saint Louis Art Museum. This is Judd’s first museum show dedicated to furniture.

On May 23, Judd receives a $50,000 award from the Frederick Weisman Foundation to fund the purchase of a Cor-ten steel vertical piece for the Contemporary Museum in Honolulu.

In June, Judd discontinues wood furniture fabrication with Jim Cooper and Ichiro Kato. Jeff Jamieson and Rupert Deese, two of Judd’s assistants in New York, take over furniture fabrication at 101 Spring Street.

In July, Judd designs new floors for the Paleis Lange Voorhout in The Hague, The Netherlands. These are loosely based on print editions he develops at the time.

Expanding on his comparatively rare practice of creating objects in editions, Judd creates a set of twelve extruded aluminum works in twelve colors in an edition of twelve (plus three artist’s proofs). These works are fabricated at Menziken AG and published by Editions Schellmann, Munich and New York. This is the only edition he will produce at Menziken.

Image: Installation view, Donald Judd, 15 x 105 x 15, 101 Spring Street, Judd Foundation, New York, April 27–July 28, 2018. Photo Sol Hashemi.

Judd travels to the Greek islands in the Aegean Sea during the summer, accompanied by family and close friends.

Judd purchases the former Sureway Store in downtown Marfa on August 16 from Helen Briam Chaffin; it will become his Ranch Office. A temporary exhibition of posters and his furniture precedes the permanent installation of eight wall reliefs and two floor works. He hangs maps of his ranch and uses the building to store saddles, ropes, and ranch documents. To the top of the façade of the Ranch Office, Judd adds “AdeC,” the ranch brand for Ayala de Chinati, and the number 76, referring to the year he purchased his first six sections of land.

Judd has his first exhibition with Pace Gallery, Donald Judd, New Sculpture, at 32 East Fifty-Seventh Street in New York.

On October 15, Ellie Meyer leaves Judd’s employ; Rob Weiner and Jeff Kopie become his chief studio assistants.

Judd creates a set of three wood-blocks produced in an edition of twenty with five artist’s proofs. The edition is published by Peder Bonnier. This is the only set of editioned wood-blocks. Each set contains the same configuration painted in red, blue, and unpainted. They are unrelated to the previous wood-blocks, which are considered to be unique objects.

On October 2, Judd purchases the historic former Crews Hotel in downtown Marfa. With the intention to install a selection of his prints dating back to 1951 in twenty-eight rooms on the upper floor and to create a space for a print studio (which was at the Block until 1991), he calls it the Print Building. Meanwhile, he permanently places two floor works in one room on the lower level.

Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen’s Monument to the Last Horse is presented to the public at the Chinati Foundation during open house in October.

Judd and Marianne Stockebrand, now director of the Kölnisher Kunstverein, form a publishing company called Der Zweite Pfeil. The first and only publication is a catalogue for the Albers exhibition at the Chinati Foundation in October. Stockebrand will eventually serve as director of the Chinati Foundation from 1994 to 2010.

In November, Judd and his son Flavin design a bottle for Marfa water and, later, sotol. The project is related to Judd’s idea for marketing local West Texas products, including asadero cheese as well as sotol. He names the project La Junta de los Rios, having arranged the legal framework for the company to move forward as early as 1989, when he filed papers of incorporation.

On December 18, Judd writes a letter to the State Attorney General of Texas complaining about low-flying Air Force jets over his ranch.

1991 Exhibition Summary

There are twenty-eight group and fourteen solo exhibitions in 1991. Judd travels extensively throughout Europe and Asia, spending time at his studios in Germany, Switzerland, New York, and Marfa. Solo gallery exhibitions take place in New York, London, Cologne, Frankfurt am Main, Berlin, Vienna, Valencia, Athens, Brussels, Paris, Madrid, and Seoul. Judd has two museum exhibitions, Donald Judd: Architektur, Österreichisches Museum für angewandte Kunst (MAK), Vienna, and Donald Judd Furniture, Saint Louis Art Museum.

Judd travels to Osaka for the opening of Donald Judd at Gallery Yamaguchi. During the presentation of Judd’s work, Gallery Yamaguchi facilitates for the planning and coordination of a traveling exhibition to take place at the Shizuoka Prefectural Museum of Art and the Kitakyushu Municipal Museum of Art.

Judd redesigns the installation of MAK’s collection of eighteenth-century furniture with curator Christian Witt-Döring.

On March 9, Judd lectures at the University of Texas at Austin School of Architecture. “I think the first act of architecture would be to do nothing whatsoever and think about it all for a few days,” he says. “The major aspect of this century, of the present, is an incredible destruction of the land. And that land is the whole history of the world, which owes nothing to us, it was there before. Including all wildlife and plants. And it is also the destruction in a very short time, of a lot of the history of the human race.”

Judd creates a design for the main plaza in the town of Gerlingen, Germany. The project is unrealized.

Judd participates in a symposium on Barnett Newman at Harvard University on May 15.

On June 3, Judd is interviewed by photographer and filmmaker Chris Felver for the documentary Donald Judd’s Marfa, Texas, with narration later provided by writer John Yau. Filmed on Judd’s sixty-fourth birthday in Marfa, the film is completed in 1995 and includes a conversation with Judd inter-cut with footage of his private living and working spaces in New York and Marfa, as well as footage of the Chinati Foundation. “I hope the [Chinati] foundation won’t be destroyed,” he says in the interview. “I think everything is against the existence of the foundation. I basically take the institutions as enemies of the existence of art and doing anything in a normal, natural way; the problem is that the foundation not be seized by the museums or by some public institution. And the foundation will have more and more works of art by other people. Also, I’d like to point out that the foundation and I are not the same thing: the foundation is a public institution, unfortunately, and at this point the foundation is a lot smaller than my own private activities and buildings. Eventually, there will be two foundations side by side—the Chinati Foundation and one using my name—all of which is to remain and be permanent.”

In June, Judd travels to Japan for the opening of his retrospective at the Shizuoka Prefectural Museum of Art, which also travels to the Kitakyushu Municipal Museum of Art. It includes two works from 1963 (DSS 35 and DSS 38), anodized aluminum works from 1988, and multicolored and plywood works from 1989. Judd gives lectures at the openings of both exhibitions.

Judds travels to Iceland, where he has an exhibition that begins in Ísafjörour and travels to Reykjavík.

Donald Judd Furniture [Plywood, Painted Aluminum, Hardwood] opens at 101 Spring Street in November.

On November 30, Judd is elected a foreign member of the Royal Academy of Fine Arts, Stockholm.

Judd creates a work consisting of two recesses in a wall; in the back of the recesses there is red, blue, or green plexiglass or galvanized iron. The work is produced in an edition of twelve with two artist’s proofs and is published by Editions Schellmann.

1992 Exhibition Summary

There are thirty-seven group shows and twelve solo exhibitions throughout Europe, United States, and Asia; the solo shows appear at venues including Inkong Gallery, Seoul, and Gallery Yamaguchi, Osaka. The latter show travels in part to Shizuoka Prefectural Museum of Art and Kitakyushu Municipal Museum of Art.

Judd meets with architects involved with the design for the Peter Merian Haus, part of Bahnhof Ost Basel, an office and university building. As described in the publication Peter Merian Haus: “Judd was initiated into the planning, immersed himself in the architectural conditions and developed proposals for the material and structure of the façade. Three things were of particular importance to him: the structure should have clear lines, be self-contained, and should have an internal organization visible from the outside.” One of Judd’s last design projects, the building is completed in 2000.

The exhibition Donald Judd Furniture: Retrospective opens at the Museum Boymans-van Beuningen, Rotterdam. A catalogue with a Judd-designed cover is published by the museum, to which Judd also contributes the essay “It’s Hard to Find a Good Lamp.” He declares that his furniture “is comfortable to me. Rather than making a chair to sleep in or a machine to live in, it is better to make a bed. A straight chair is best for eating or writing. The third position is standing.”

On October 4 and 5, Judd is interviewed by art historian and filmmaker Regina Wyrwoll for the television documentary Bauhaus, Texas. This is Judd’s final filmed and complete interview.

RW: “The presentation of your own collections here—you chose every piece and you personally placed it?

DJ: “Yes—a great deal of time and thought went into the process. The front room of the east building at La Mansana probably took two years. It will never change. It’s too much work and too much thought. It’s like making another work of art. If the individual works are short stories, those buildings are the novels, and they’re just too much effort. And I’m very careful about what goes next to what and the space each thing has and the contradictions between the civilizations and lots of other considerations.”

RW: “How would you describe Marfa yourself?”

DJ: “In a way, it’s totally an art project, or art and architecture. Naturally, everything here is financed by the art market, by selling my work. A little bit now, happily, by architecture. So it just comes from money that I can make one way or the other. The furniture brings in some money. When there’s no money coming, we save a little by eating our own steers, but otherwise no money comes from West Texas. All the money is coming in from around the world. It’s mainly about making the art and then installing the art, both mine and other people’s. And of course it’s what I want to do. It’s what I like to do. It’s not wildly altruistic.”

The exhibition Donald Judd: Prints 1951–1993, Retrospektive der Druckgraphik opens at the Gemeentemuseum Den Haag; the show is curated by Mariette Josephus Jitta. A catalogue raisonné of prints, titled Donald Judd, Prints and Works in Editions: A Catalogue Raisonné, is published by Editions Schellmann, Munich and New York, coedited by Mariette Josephus Jitta and Jorg Schellmann.

In November, Texas-based photographer Laura Wilson photographs Judd in Marfa. This is the last time he is professionally photographed.

From November 26 to December 10, Judd is hospitalized in Cologne, where he is diagnosed with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

A major exhibition of Judd’s work at the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, curated by Rudi Fuchs, opens on the occasion of Judd receiving the Sikkens Prize “for the use of color in art” from the Sikkens Foundation, Amsterdam, on November 27. Judd is unable to attend, but his last essay is read on his behalf. The essay, “Some Aspects of Color in General and Red and Black in Particular,” is published by the Sikkens Foundation and later reprinted in the Artforum summer 1994 issue. “The three-dimensional work that I began in 1962 was new and the complete use of color was new,” he writes. “While I was making the first two works and the right angle I realized that there had been no such work before. I was puzzled by them, especially the first, the relief that isn’t a relief. I had made what I wanted. . . . The new work seemed to be the beginning of my own freedom, with possibilities for a lifetime. The possibilities and the lifetime are now well along.”

In December, Judd receives the Stankowski Prize from the Stankowski Foundation, Stuttgart, on the occasion of his retrospective exhibition Kunst + Design: Donald Judd, curated by Volker Rattemeyer and Renate Petzinger at the Museum Wiesbaden. This is the last retrospective exhibition Judd is directly involved in. As Rattemeyer notes, “The exhibition project initiated and sponsored by the Stankowski Foundation, scheduled to begin in Wiesbaden before moving to Chemnitz, Karlsruhe, Oxford and Berlin, is an attempt to present the full spectrum of Judd’s work in art and in architecture as a whole and to underscore the mutual interdependence of the two aspects. The exhibition brings together Judd’s three-dimensional objects, his prints and drawings, his furniture, his architectural designs and his posters. The catalogue [Donald Judd: Raume – Spaces] confronts this programme with a documentation of Judd’s own ideas about the ideal concept of a museum, illustrating the manner in which he has put these ideas into practice, initially in New York, later in West Texas and more recently in Eichholteren near Küssnacht on the Rigi.”

1993 Exhibition Summary

There are twenty-three group shows throughout the United States, Europe, and Asia and seven solo exhibitions. Among them are Donald Judd Furniture: Retrospective, Museum Boymans-van Beuningen, Rotterdam (subsequently traveling to Villa Stuck, Munich); Donald Judd: werken uit Nederlandse openbare collecties en een Belgische privé verzameling t.g.v.de Sikkensprijs 1993 (Works from Dutch Public Collections), curated by Rudi Fuchs, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Kunst + Design: Donald Judd, curated by Volker Rattemeyer and Renate Petzinger, Museum Wiesbaden (subsequently traveling to Kunstsammlungen Chemnitz; Badisches Landesmuseum Karlsruhe; Museum of Modern Art, Oxford; and Kunsthallen Brandts Klædefabrik, Odense); and Donald Judd: Prints 1951–1993, Retrospektive der Druckgraphik, Gemeentemuseum Den Haag, curated by Mariette Josephus Jitta (later traveling to Haus für konstruktive und konkrete Kunst, Zürich; Österreichisches Museum für angewandte Kunst, Vienna; Institut Valencia de’Art Modern, Valencia; and Museum Wiesbaden).

Judd dies in Manhattan on February 12. He is buried at Ayala de Chinati, his ranch in far West Texas. Judd’s will, with the exception of two bequests, directs that Judd Foundation shall be the beneficiary of his estate.

1994 Exhibition Summary

There are a number of exhibitions organized by galleries and curators with whom Judd worked closely. It is a testament to their personal and professional relationships, some many decades long, to carry forward their commitment to his work. Throughout the year, his estate continues to fulfill exhibitions planned by Judd during his lifetime. Among them are: Donald Judd: The Moscow Installation, Galerie Gmurzynska, Cologne, March 5–May 21 (organized by Rudi Fuchs); Memorial Show for Donald Judd, Gallery Yamaguchi, Tokyo, March 25–April 28; Donald Judd: The Last Editions, Brooke Alexander Gallery, New York, September 10–October 29; Donald Judd: Sculpture, PaceWildenstein, New York, September 16–October 15 (organized by William C. Agee); Donald Judd (1928–1994), Annemarie Verna Galerie, Zürich, November 26, 1994–February 11, 1995.

Judd, “Marfa, Texas,” in Donald Judd Writings, 430.

“Interview with Pilar Viladas” (1985), in Donald Judd Interviews, 540.

Judd, “Marfa, Texas,” in Donald Judd Writings, 430.

“Interview with Russell Connor for the television documentary American Art ’85” (1985), in Donald Judd Interviews, 556.

“‘Donald Judd: Great Art through Simple Means,’ interview with Lars Morell for Skala” (August 30, 1993), in Donald Judd Interviews, 846–47.

Judd, “Cleveland” (1989), in Donald Judd Writings, 603.

Judd, “On Furniture,” in Donald Judd Writings, 451.

Judd, note from 6 December 1986, in Donald Judd Writings, 445.

“Interview with Paul Cabon,” in Donald Judd Interviews, 600–601.

Judd, “Monument to the Last Horse: Animo et Fide” (1992), in Donald Judd Writings, 795.

Judd, “Statement for the Chinati Foundation/La Fundación Chinati” (1987), in Donald Judd Writings, 486.

“Interview with Regina Wyrwoll for the television documentary Bauhaus, Texas,” in Donald Judd Interviews, 862.

Judd, “Donald Judd’s View,” Blueprint, February 1988, 31.

“‘A Change in a Degree That Is Valid for Good Art,’ interview with Markus Brüderlin for Kunstform International” (November 1987), in Donald Judd Interviews, 620.

Judd, “Monument to the Last Horse: Animo et Fide,” in Donald Judd Writings, 795.

Judd, “Richard Paul Lohse” (1988), in Donald Judd Writings, 516.

Judd, note from 25 February 1989, in Donald Judd Writings, 524.

Judd, “Ausstellungsleitungsstreit” (1989), in Donald Judd Writings, 558.

Donald Judd Papers, Judd Foundation Archives, Marfa, Texas.

“Architecture Studio,” in Donald Judd Spaces (New York: Judd Foundation/Prestel DelMonico Books, 2020), 256.

“‘Discussion with Donald Judd,’ seminar discussion with Angeli Janhsen (moderator) and students from the Ruhr-Universität Bochum from the exhibition catalogue Donald Judd” (February 1, 1990), in Donald Judd Interviews, 694.

“Interview with Regina Wyrwoll for the television documentary Bauhaus, Texas,” in Donald Judd Interviews, 859.

Judd, “Una stanza per Panza,” in Donald Judd Writings, 630.

“‘War Destroys Culture,’ interview with Ólafur Gíslason for Pjódviljinn” (January 20, 1991), in Donald Judd Interviews, 740.

Donald Judd Papers, Judd Foundation Archives, Marfa, Texas.

“Interview with Chris Felver for the film Donald Judd’s Marfa, Texas” (June 3, 1992), in Donald Judd Interviews, 800.

Margherita Spiluttini and Hans Zwimpfer, Peter Merian Haus Basel: At the Interface Between Art, Technology and Architecture = An Der Schnittstelle Von Kunst, Technik Und Architektur (Basel: Birkhauser, 2002), 23.

Judd, “It’s Hard to Find a Good Lamp” (1993), in Donald Judd Writings, 831.

“Interview with Regina Wyrwoll for the television documentary Bauhaus, Texas,” in Donald Judd Interviews, 868.

Judd, “Some Aspects of Color in General and Red and Black in Particular,” in Donald Judd Writings, 851–52.

Volker Rattemeyer, Kunst + Design: Donald Judd, Preisträger der Stankowski-Stiftung 1993/Art + Design: Donald Judd, Recipient of the Stankowski Prize 1993. Exh. cat. (Ostfildern: Cantz, 1993), 7.