Judd writes the essay “Imperialism, Nationalism, and Regionalism,” contesting the term “American art.” “This article is pretty general, so, to add another general statement, the world is usually thought of and felt as a whole in ways I don’t agree with and also divided in ways I don’t agree with,” he declares. “As I wrote several years ago I’m very wary of general statements, certainly the usual solipsistic ones, and also I’m wary of my own. The different kinds of activities should become discrete, should be considered only as a function if useful, and only as knowledge if that’s the purpose. Art, dance, music, and literature have to be considered as autonomous activities and not as decoration upon political and social purposes. Only in China and Russia is it still 1935. One thing this separation of activities means is that business should be considered only as production and supply and divested of its great aura of moral, social, and political assumptions. I’m tired of being governed by the men who produce my oil, the children’s milk, or move the products around.”

Judd’s retrospective opens at the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, running from May 24 to July 6. The exhibition, organized by Brydon Smith, includes over fifty works. Donald Judd: Catalogue Raisonné of Paintings, Objects, and Wood-Blocks 1960–1974, edited by Dudley Del Balso, Brydon Smith, and Roberta Smith, is published in conjunction with the exhibition.

Image: Installation view, Donald Judd, The National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, Canada, May 24–July 6, 1975. Courtesy The National Gallery of Canada.

Image: Donald Judd: Catalogue Raisonné of Paintings, Objects, and Wood-Blocks 1960-1974, edited by Dudley Del Balso, Brydon Smith, and Roberta Smith, on the occasion of his retrospective exhibition at the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, 1975.

Donald Judd: Complete Writings 1959–1975 is published by The Press of the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design and New York University Press. This comprehensive collection of Judd’s writing to date helps solidify his position as an influential thinker and critic. When the book is reissued in 2005, Mel Bochner writes, “For my generation, Judd posed the same problem as Picasso did for the Abstract Expressionists; you either had to go over, under, around or through him.”

Image: Donald Judd: Complete Writings 1959-1975, published: Halifax, Nova Scotia/New York: Press of the College of Art and Design/New York University Press, 1975, 2005; Judd Foundation, 2015.

The Judd family lives intermittently in Marfa at the Lujan House from August through October.

In September, Judd is interviewed by documentary filmmaker Michael Blackwood for The Artist’s Studio: Donald Judd. This portrait is filmed in Marfa, Texas, and at 101 Spring Street in the second-floor living space and on the third floor, which Judd uses as his studio.

In December, Judd designs a prototype for a collar and bracelet with green or blue stone, aquamarine, emerald, or tourmaline, for submission to Montebello, an Italian company that produces editions of artists’ designs. The jewelry is not produced.

1975 Exhibition Summary

Judd’s retrospective exhibition Donald Judd, curated by Brydon Smith, is presented at the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa. In addition, Judd has solo gallery exhibitions in Paris, London, Stockholm, Cologne, and Naples, as well as work in nineteen group exhibitions in the United States, Canada, and Europe. Donald Judd: Complete Writings 1959–1975 is published by The Press of the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design and New York University Press in the spring.

Judd spends increasing amounts of time in Marfa. Local workers begin construction of an adobe wall enclosing the perimeter of the Block. The wall is built with repurposed adobe bricks from two demolished Marfa buildings, the Toltec Motel and Virginia Hotel, as well as adobe bricks made on-site by local adoberos.

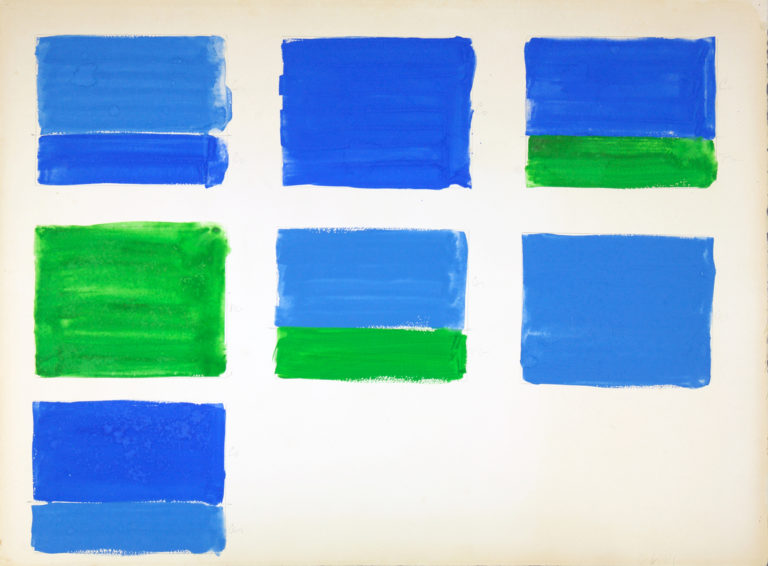

The first set of right-facing parallelogram wood-blocks (the wood object from which prints are pulled) are commissioned by collector Peder Bonnier in February 1976. This group, fabricated by wood craftsmen Jim Cooper and Gary Williams, is painted using artist’s oil paint thinned with linseed oil according to Judd’s specifications.

A solo exhibition, Donald Judd Skulpturen, is presented at Kunsthalle Bern. Judd installs five plywood site-related works made to fit the dimensions of the five rooms of the museum. The works can be rebuilt in different dimensions.

Judd’s first retrospective of drawings, Donald Judd: Zeichnungen/Drawings 1956–1976, is organized by curator Dieter Koepplin and presented at Kunstmuseum Basel. The exhibition travels to Tubingen, Vienna, Geneva, and The Netherlands. Koepplin writes in the accompanying catalogue, “Since Judd, when he produced his first 3-dimensional works in 1962/64, was only able, for reasons of economy to fabricate a few pieces in wood, he seems to have had all the more need to put into the drawings of the pieces he was planning the greatest possible legibility: as a ‘record’ of the piece developing in his imagination (‘just to record the idea,’ as he said in a 1965 interview).” The exhibition is accompanied by a catalogue designed by Eiko Emori, which includes drawings for works later made or rejected.

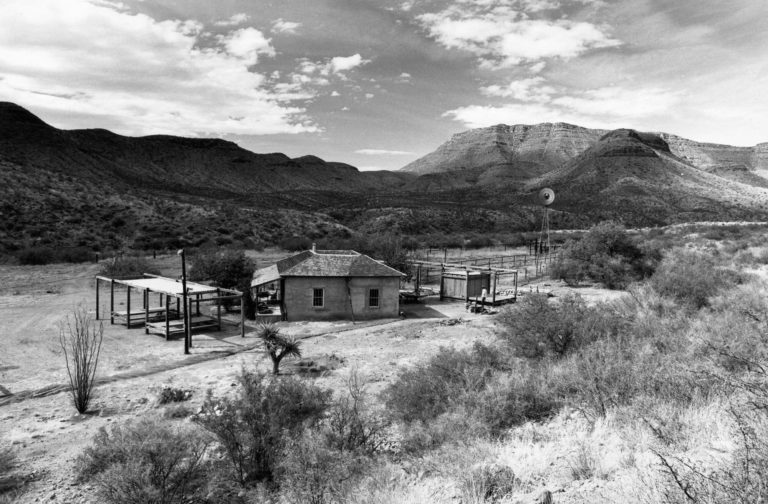

Judd purchases six sections of the Morales Ranch (Ranch Alamito) in Presidio County, Texas. Each section is a square mile (640 acres). These are the first of a total of 51.8 sections that Judd will come to own. The accompanying ranch house was built by local stone masons for Jose Prieto (the landowner and father-in-law to rancher Juan Morales). The house was built around 1945 at the base of Sierra Parda, the second highest peak in the Chinati Mountains.

In May, Judd purchases a small house in Marfa known as the Walker House, named after a previous owner and located a block away from the Presidio County Courthouse. The back room is used as a painting studio by Judd’s studio assistant Jamie Dearing. He later installs paintings by John Wesley throughout the main house. A small orchard is laid out in a grid pattern adjacent to the house on the south side.

Judd meets architect and artist Lauretta Vinciarelli. Raised in Rome, Vinciarelli studied and practiced architecture in Italy prior to moving to the United States in 1968. She teaches architectural design at several institutions, including Columbia University. Judd acquires several of her watercolors. This same year, Vinciarelli becomes the first woman to have drawings acquired by The Museum of Modern Art’s Department of Architecture and Design.

In October, the Friends of Cast-Iron Architecture award Judd and Finch a certificate of commendation honoring their preservation and renewal of 101 Spring Street as a “significant part of America’s Cast-Iron Architectural Heritage for Succeeding Generations to Appreciate and Use.”

1976 Exhibition Summary

Judd participates in nineteen group and eight solo exhibitions, including two European drawing shows: a retrospective titled Donald Judd: Zeichnungen/Drawings 1956–1976, Kunstmuseum Basel (traveling to Kunsthalle Tubingen; Museum Moderner Kunst, Vienna; and Musee d’Art et d’Histoire, Geneva), and Donald Judd: Drawings 1956–76, Museum of Modern Art, Oxford.

Judd writes an essay titled “Judd Foundation,” subsequently named both “Austin Street Foundation” and “In Defense of My Work,” in which he lays out his plan for a foundation to carry on his vision for his buildings and art in Marfa. “The purpose of the foundation is to preserve my work and that of others and to preserve this work in spaces I consider appropriate for it,” he writes. “This effort has been a concern second only to the invention of my work. And gradually the two concerns have joined and both tend toward architecture. . . . The installation of my work and of others is contemporary with its creation. The work is not disembodied spatially, socially, temporally, as in most museums. The space surrounding my work is crucial to it: as much thought has gone into the installation as into a piece itself. The installations in New York and Marfa are a standard for the installation of my work elsewhere.” Expressing his growing frustration with the commercial art situation, he writes, “The brief time of gallery and museum exhibitions would be ultimately fatal if it were not for the permanence of my own installations.”

In March, Judd exhibits a group of fifteen plywood floor works in a traveling exhibition at the Heiner Friedrich Gallery, New York, and later at the Contemporary Arts Center, Cincinnati. The configuration of these works relates to the configuration of a group of sixteen plywood wall meter boxes. A meter box is a wall piece with exterior dimensions of fifty by one hundred by fifty centimeters, regardless of material or internal configuration.

Judd’s work is exhibited alongside that of Josef Albers in Donald Judd für Josef Albers at the Moderne Galerie Bottrop. Albers, who was born in Bottrop, had passed away on March 25 of the previous year. In an interview with curator Kasper König for the accompanying catalogue, Judd states, “One field in my work has a lot to do with Albers. I always admired his paintings. I tended to relate to him in ideas.”

By the end of May, Judd is firmly established in Marfa, spending much of his time overseeing work at the Block and living at the Lujan House. With local carpenters and brothers Celedonio Mediano Jr. and Alfredo Mediano, Judd makes a bed with a vertical divider for his two children at the Lujan House. For the two-story building at the Block, Judd makes desks, chairs, beds, the first single daybed, tables, stairs, closets, shelves, kitchen counters, and a large dining room table.

Judd’s only permanently sited outdoor work in aluminum is dedicated on the campus of Northern Kentucky University in Highland Heights on June 10. Judd, as artist, and Ed Bernstein, as fabricator, disagree on how this work should be made, pitting aesthetic concerns against structural ones. The argument leads to a temporary stall in the fabrication of Judd’s works at Bernstein Brothers.

Dudley Del Balso facilitates a working relationship between Judd and Lippincott, Inc., a fabricator in North Haven, Connecticut. The first work is a brass and violet plexiglass floor work.

In June, Judd makes an outdoor work for the City of Münster. The work has two concentric concrete circles. The outer circle follows the natural slope of the land; the inner circle is level across the top plane. Each circle is sixty centimeters thick and the two are separated by a distance of the same width.

Judd later proposes three more circular works for Münster, which he describes as “facing the lake, one to the right, with the rings reversed, the outer level and the inner level parallel, and two opposite in the lake, the left a double ring flush with the water, with the space between a space in the water, and the right a single ring, also flush with the water, enclosing the large area of water within at a meter or a meter and a half below the surface of the lake.” The proposal remains unrealized.

Judd exhibits his first concrete rectangular prism work in the exhibition Donald Judd: Concrete, Ace Gallery, Venice, California. This five-unit floor work is one of the last concrete works of this type to be cast whole. Later works are constructed in slabs and bolted together.

1977 Exhibition Summary

Judd has six solo exhibitions and work in thirty group shows in the United States and Europe. He oversees the fabrication and installation of three site-specific outdoor works: in Cor-ten steel at the Josef Albers Museum, Bottrop; in concrete for the City of Münster; and in aluminum at Northern Kentucky University.

Judd travels to Japan for his first solo exhibition in the country, The Sculpture of Donald Judd, Galerie Watari, Tokyo. He shows three wall works, five drawings, and two woodcuts.

In May, Judd travels to Vancouver for Donald Judd, a solo exhibition at Vancouver Art Gallery. The catalogue for this exhibition includes Judd’s essay “Imperialism, Nationalism, and Regionalism” and an essay by Brydon Smith, “Random Thoughts Three Years Later.”

In June, Judd enters into discussions with Philippa de Menil and Heiner Friedrich, who have recently founded Dia Art Foundation. The “Marfa project,” a permanent place for art in Marfa, will later be named the Art Museum of the Pecos and, finally, the Chinati Foundation/La Fundación de Chinati. Judd’s attorney John Jerome stresses the importance that Judd have a written agreement in place.

Judd travels to the Otterlo opening of his traveling exhibition Donald Judd: Drawings 1956–76 at the Rijksmuseum Kröller-Müller. He continues to Eindhoven in June.

In November, Judd is interviewed for a film being made by eighth-grade students from Marfa Elementary School, where his children have been enrolled since September 1977. In response to a student asking whether his sculptures have any special meaning, Judd replies, “They have a lot of meaning, but they’re visual, so it’s not easily translated into words.” May Quick, the students’ art teacher, taught both of Judd’s children.

1978 Exhibition Summary

Despite spending much of his time in Marfa, Judd has work in twenty group exhibitions and travels to oversee and approve ten solo exhibitions on view in Europe, Asia, Canada, and various cities in the United States.

Heiner Friedrich and Philippa de Menil, through Dia Art Foundation, promise money and long-term support to Judd and a number of other artists, including Dan Flavin, Bob Whitman, La Monte Young, and Walter De Maria. Due to the insistence of his lawyer, John Jerome, Judd is the only artist in the group with a legal agreement with the foundation.

In January, the first contract between Judd and Dia Art Foundation is signed, with Dia agreeing to pay for the fabrication of forty-four Judd works: thirteen progressions, three stacks, two stainless-steel floor works, one channel work, and twenty-five mill aluminum floor works. The works are to be installed in buildings throughout Fort D. A. Russell.

Judd and Finch divorce in February. Judd is granted custody of their children.

Donald Judd: Survey of Work, 1963–1979 is exhibited at Leo Castelli Gallery.

On April 29, Judd lectures on Barnett Newman’s work at the Baltimore Museum of Art in conjunction with the exhibition Barnett Newman: The Complete Drawings, 1944–1969.

In May, Dia Art Foundation and Judd sign a contract covering maintenance of works by Judd, Dan Flavin, and John Chamberlain as part of the “Marfa project.” “In 1979, in accordance with my idea of permanent installations, I agreed to have Dia Art Foundation come to Marfa and purchase the land and main buildings of Fort Russell on the edge of town, to make permanently maintained public installations of contemporary art,” Judd later recounts. “My idea was to have large, careful installations of my own work, pieces made for the place, and smaller, but still large, installations of the work of Dan Flavin, also to be made for the site, and the work of John Chamberlain. Later it was planned that the complete prints of Barnett Newman would be permanently shown. I didn’t want to make a comprehensive collection of contemporary art or even of the artists whose work I liked, imitating the museums. I had in mind, though, originally, one piece each outside by Carl Andre, Richard Serra, Claes Oldenburg, and Richard Long, and inside, the two very dark rooms that Larry Bell constructed in his studio in Venice, California, and in The Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1969.”

Image: Installation view, Donald Judd, Stedelijk van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven, The Netherlands, April 26–June 2, 1979. Photo courtesy Stedelijk van Abbemuseum.

In May, Judd and his children leave for Scotland, Germany, and The Netherlands for the opening of Donald Judd, curated by Dutch art historian Rudi Fuchs, at the Stedelijk Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven (April 26–June 2). They return to Marfa in late June. Fuchs will become a lifelong friend and advocate of Judd’s work.

On July 20, Dia Art Foundation purchases the Marfa Wool & Mohair Building for the installation of John Chamberlain’s work, along with a portion of Fort D. A. Russell.

1979 Exhibition Summary

Judd has work in twenty group exhibitions, six solo gallery exhibitions in the United States and Europe, and one major solo museum exhibition at the Stedelijk Van Abbemuseum.

Throughout much of the year, Judd is occupied with negotiating contracts with Dia Art Foundation and the fabrication of his own art intended for permanent installation at Fort D. A. Russell. In March, Dia agrees to produce seventy-five mill aluminum floor works in addition to the first twenty-five, bringing the total installation to one hundred. On April 21, an agreement between fabricator CRS and Dia Art Foundation is signed that covers the fabrication of the first two of fifteen outdoor concrete works. In May, the first twenty-five works in mill aluminum are ordered from Lippincott, Inc. The U-shaped buildings and the Arena are purchased by Dia in August.

Judd participates in Carl Andre, Donald Judd, Robert Morris: Sculpture Minimal, three separate exhibitions at the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna, Rome.

In early May, Judd travels to Sicily with Lauretta Vinciarelli, with whom he has now established a personal and professional relationship. Vinciarelli and Judd will collaborate on a number of projects well into the 1980s.

From May 16 through June 8, Judd continues his travels in Italy with his children and studio assistant Jamie Dearing. They stay at Giuseppi Panza’s villa in Varese, where they encounter problems with the fabrication of some of the installed Judd works. Dearing writes several letters to Panza over the course of the next year describing these issues.

Judd exhibits a large floor work in hot-rolled steel at the thirty-ninth Venice Biennale, the first Venice Biennale in which his work is shown.

1980 Exhibition Summary

Judd works are included in thirty museum and gallery group exhibitions in Rome, Paris, London, Stuttgart, Düsseldorf, Zürich, New York, Los Angeles, Seattle, and other cities. Judd’s work is also included in the thirty-ninth Venice Biennale.

On April 7, Judd and Dia Art Foundation sign amended contracts after a year of negotiations. The agreement guarantees Dia’s maintenance and ownership of all works, land, and buildings at Fort D. A. Russell and the Chamberlain Building, formerly the Marfa Wool & Mohair Building, in perpetuity.

In May, Judd travels to Ireland, Scotland, Germany, and Switzerland, continuing to Italy in June. He shows work at the Internationale Ausstellung Köln 1981.

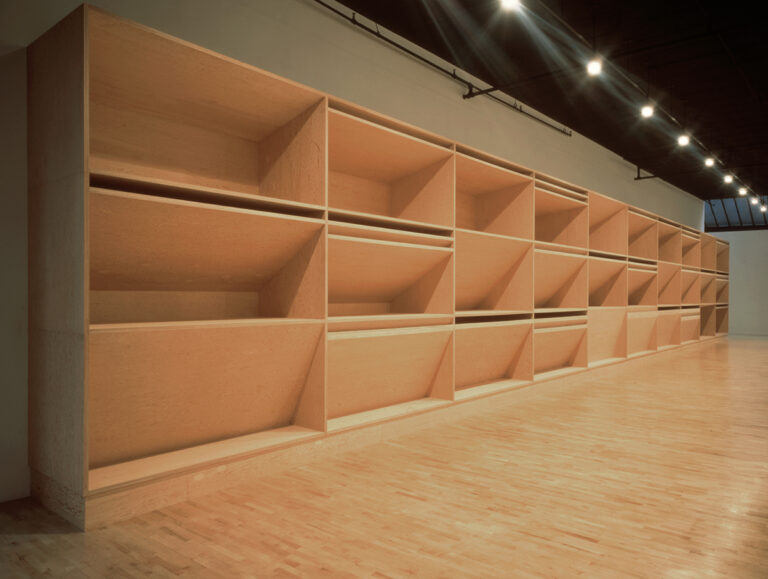

After a six-week installation period overseen by the work’s fabricator, Peter Ballantine, an exhibition of Judd’s untitled (1980) opens to the public at Leo Castelli Gallery, Greene Street, New York, on September 15. The work is constructed in Douglas fir plywood and measures twelve feet high by eighty feet long. It consists of ten contiguous columns, each with three rows.

Judd exhibits a stainless steel with blue plexiglass work in Cy Twombly, Richard Shaw, Donald Judd at Newport Harbor Art Museum in Newport Beach, California. Through this experience, he reestablishes a professional relationship with Cathleen Gallander, the show’s curator and the previous director of the Museum of South Texas, who will become his studio manager in the summer of 1983.

Trisha Brown Dance Company’s Son of Gone Fishin’ premieres on October 16 at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, featuring set design by Judd.

Image: Donald Judd, study for Trisha Brown Dance Company’s Son of Gone Fishin’, October 1981, gouache on paper. Judd Foundation.

1981 Exhibition Summary

Judd has three solo exhibitions and work in eighteen group shows, including The Artists’ Benefit for the Trisha Brown Dance Company, Leo Castelli Gallery, in May.

The fabrication of Judd’s wood furniture begins in New York by craftsmen Jim Cooper and Ichiro Kato. Some of the first pieces of furniture made are a desk with two matching chairs, a single daybed, and chairs in various configurations.

In June and July, Jack Wesley and Hannah Green stay in Marfa. Green will later recall that “Wesley begins a series of nine paintings for the John Wesley Museum to be built there in adobe.” Judd supported Wesley’s work by purchasing his paintings on a regular basis, with the intention to install them permanently. Judd often funded Wesley and Green’s annual summer writing and painting retreat to France.

Judd includes two works in Documenta 7 and writes the essay “On Installation” for its exhibition catalogue. The exhibition is held in Kassel and is overseen by artistic director Rudi Fuchs. In his essay, Judd writes, “The installation and context for the art being done now is poor and unsuitable. The correction is a permanent installation of a good portion of the work of each of the best artists.”

In November, the first twenty-one works in mill aluminum are installed in the south artillery shed at Fort D. A. Russell.

Judd and Lauretta Vinciarelli give a lecture on architecture at Cooper Union in New York on December 16.

1982 Exhibition Summary

Judd’s work is included in one solo exhibition, Donald Judd, Larry Gagosian Gallery, Los Angeles, and twenty group exhibitions including Documenta 7, which is overseen by Rudi Fuchs. Judd writes “On Installation” for the Documenta 7 exhibition catalogue.

On March 10, Judd moves his children from Marfa to New York to take advantage of better educational opportunities. He leaves the bulk of the “Marfa project” administrative duties in the hands of his office manager, Willie Null, and oversight of the grounds and buildings to Henry and Lorina Naegele.

Judd exhibits a selection of Lauretta Vinciarelli’s drawings on the first floor of 101 Spring Street.

Judd hires Rob C. Wilson to oversee renovations at 101 Spring Street and to work as his studio assistant.

Heiner Friedrich informs Judd that the “Marfa project” must become an independent and self-sufficient entity and that he intends to reduce financial support for it. By December, John Jerome and his team at Milbank, Tweed, Hadley & McCloy represent Judd, proceeding with the legal work necessary for the project to become a nonprofit organization no longer constrained by Dia Art Foundation. A three-year negotiation between Judd and Dia ensues for control of the artwork and property. A settlement is reached August 1, 1986.

Judd acquires additional sections of ranch land in Presidio County, Texas. The land includes Casa Perez, a house built by Juan Nuñez, whose family settled in Pinto Canyon in the 1910s. Jose Prieto purchased the land and house for his son Gregorio and Gregorio’s wife, Pilar, daughter of Juan Nuñez. After Gregorio survived a gunshot wound from a Texas Ranger, the couple moved to Mexico. The house then passed to Frances Prieto, sister of Gregorio, and husband Manuel Perez, for whom Judd names the ranch house.

The Chamberlain Building opens to the public on April 13. It features the permanent installation of twenty-two works by the artist and will eventually become part of the Chinati Foundation.

Beginning in the summer, Judd collaborates with Lauretta Vinciarelli on a large-scale proposal for a sequence of six circular concrete structures in Providence, Rhode Island. Judd and Vinciarelli win the competition, but the project is not realized. Judd later writes, “We explained the circle, the several circles, the history, preservation, function, even circulation. We did a good job, and went back to New York. Eventually I got a letter saying that the competition we had won had been called off and that another would be held. And all told that’s why nothing happens.”

On July 1, Judd hires Cathleen Gallander to take over daily oversight of his art business, including gallery, museum, and fabrication operations. She works out of 101 Spring Street.

On September 20, Judd lectures at Yale University on the relationship between art and architecture; a transcript will be published in Res: Anthropology and Aesthetics in the following year. Judd meets artist Meg Webster while doing studio visits at Yale during this trip. The following year, Judd will exhibit Webster’s Two Walls at 101 Spring Street.

In November, Judd hires Ellie Meyer as a part-time assistant to Cathleen Gallander at 101 Spring Street. Meyer becomes Judd’s studio manager shortly thereafter.

On November 21, Judd agrees to donate a small work to the multi-city benefit exhibition Artists Call Against U.S. Intervention in Central America, organized by Coosje van Bruggen.

1983 Exhibition Summary

Judd has five solo and twenty-five group exhibitions. Three exhibitions are dedicated to drawing, including the Whitney Museum of American Art’s The Sculptor as Draftsman. The exhibition Concepts in Construction, 1910–1980, Tyler Museum of Art, Tyler, Texas, will travel for the next two years.

Judd is enthusiastic about the possibilities of making art and furniture utilizing color in a new way. He writes, “In 1984 I began making works of art at Lehni AG in Dübendorf. Their business is mainly that of making metal furniture, itself practical and handsome, without affectation, which is present in almost all furniture, including that which is usually said to be ‘well designed.’ Their furniture does not symbolize the past, the future, the rich or the rustic. . . . In less than two weeks, thanks to the foremen Alfred Lees and Willi Bühler, who made it, there was an aluminum chair, later colored red, in baked enamel. Doris Lehni Quarella and I discussed the furniture and we made several more, finally making ten for a show at the Max Protetch Gallery, New York, in December 1984.” The exhibition at Max Protetch Gallery is Judd’s first major presentation of furniture at a commercial gallery in the United States.

The first large-scale multicolored work is produced for Skulptur im 20. Jahrhundert, at Merian-Park in Brüglingen, Switzerland.

Judd travels to Russia for the first time, with choreographer and dancer Wendy Perron, arriving in Leningrad on June 25. He is greatly impressed by the State Hermitage Museum and the Piskaryovskoye Memorial Cemetery, the burial ground from the Siege of Leningrad.

“A Long Discussion Not About Master-Pieces but Why There Are So Few of Them: Part I” is published in the September issue of Art in America, followed by “Part II” in the magazine’s October issue. In the essay, Judd describes the lack of serious art criticism and explains the connection between criticism and commerce, lamenting the fate of good art being shown outside New York and Los Angeles, art rarely reviewed at the national level. He begins “Part II” by stating, “None of the groups that can be expected to defend serious art do so, neither the critics, the museums, the galleries, the educators, not even the artists. All of these can say that now there is more art, which there is, and that that’s an improvement. But there is less good art. It’s not enough to report on every mediocrity, to commission every lawn sculpture, to run every beginner through the museums, to be tolerant of everything. Quality, which is thought, breadth, intent, work, endurance, and experience, all comprehensible matters, is nearly the definition of art.”

A solo exhibition, Painted Wall Sculptures, opens at Margo Leavin Gallery in Los Angeles. The exhibition includes eleven works in total, seven of which are multicolored works fabricated by Lehni AG.

“Criticism at the Crossroads,” a roundtable discussion with Judd, Lucy Lippard, art critic and poet Donald Kuspit, Clement Greenberg, art critic and poet Carter Ratcliff, and Leon Golub, is held at New York University on November 29. The discussion is moderated by Susan Sontag.

1984 Exhibition Summary

Judd has five solo exhibitions, including Donald Judd Furniture, fabricated by Jim Cooper and Ichiro Kato, at 101 Spring Street and Judd: Architectural Drawings and Furniture, Max Protetch Gallery, New York. There are thirty-six group shows, including four benefit exhibitions: Artists Call Against U.S. Intervention in Central America Benefit Exhibition, First Annual Art Auction Benefit for the Gay Men’s Health Crisis, Foundation for the Community of Artists Fundraising Auction Sponsored by Christie’s, and Artists’ Weapons: A Response to the Arms Build Up. Judd’s first large-scale multicolored work, fabricated at Lehni AG in Switzerland, is installed in Skulptur im 20. Jahrhundert, Merian-Park, Brüglingen, Switzerland.

Judd, “Imperialism, Nationalism, and Regionalism” (1975), in Donald Judd Writings, 279.

Mel Bochner, “Mel Bochner on Donald Judd,” Artforum, Summer 2005.

“Interview with Barbara Rose for the film American Art in the 1960s,” in Donald Judd Interviews, 394.

Dieter Koepplin, Donald Judd: Zeichnungen/Drawings 1956–1976. Exh. cat. (Basel: Kunstmuseum Basel, 1976), n.p. The interview mentioned in this quote was with Barbara Rose and Frank Stella and dates to 1966–67; see Donald Judd Interviews, 154.

Caitlin Murray and Rebecca Siefert, “Lauretta Vinciarelli.” Exh. pamphlet (New York: Judd Foundation, 2019), n.p.

Donald Judd Papers, Judd Foundation Archives, Marfa, Texas.

Judd, “Judd Foundation” (1977), in Donald Judd Writings, 285–86.

“‘Interview: Kasper König and Donald Judd’ for the exhibition catalogue Donald Judd” (1977), in Donald Judd Interviews, 506.

Judd, “21 February 1993” (1993), in Donald Judd Writings, 815–16.

Brydon Smith, Donald Judd. Exh. cat. (Vancouver: Vancouver Art Gallery, 1978), n.p.

“Interview with eighth-grade students from Marfa Junior High School” (November 1978), in Donald Judd Interviews, 521.

Donald Judd Papers, Judd Foundation Archives, Marfa, Texas.

Judd, “Marfa, Texas,” in Donald Judd Writings, 429.

Murray and Siefert, “Lauretta Vinciarelli.”

Hannah Green, John Wesley: Selected Paintings, 1963–1973. Exh. brochure (New York: Fiction/Nonfiction, 1991), n.p.

Judd, “On Installation,” in Donald Judd Writings, 309.

Judd, “Providence” (1989), in Donald Judd Writings, 601.

Judd, “Art and Architecture” (1983), in Donald Judd Writings, 338.

Judd, “On Furniture,” in Donald Judd Writings, 453.

Judd, “A Long Discussion Not About Master-Pieces but Why There Are So Few of Them: Part II” (1984), in Donald Judd Writings, 378.