In July, Judd enrolls in the General Studies program at Columbia University while continuing day classes at the Art Students League. For the next two years, to save money, he commutes daily from his parents’ home in New Jersey to Manhattan.

Judd participates in his first group show, the Washington Square Outdoor Exhibition, and receives first prize for a lithograph, The League Stairwell. He also participates in the Twenty-Second Annual New Jersey State Exhibition, at the Montclair Art Museum, in which he exhibits an oil painting, 34 Gramercy Square, and a charcoal drawing, Study of Quarry Near Closter, NJ. He receives the American Artists Professional League Award of $50 for the drawing.

Over the summer, Judd moves to Manhattan, where he rents Louis Bosa’s studio. In the fall, he moves to a cold-water railroad flat on the first floor of 304 East Twenty-Seventh Street, followed by a slightly improved one on the second floor of 302 East Twenty-Seventh Street.

On October 28, Judd graduates cum laude from Columbia University with a bachelor’s in philosophy. His studies include logical/positivist and pragmatist thought and courses on Descartes, Spinoza, and the British empiricists. Judd stops attending the Art Students League and obtains a part-time job at Grand Central Art Supply, where he works through the Christmas holiday.

Judd works at the Columbia University library during the spring and part of the summer. He eventually obtains a more permanent part-time job at Christodora House. Located on Ninth Street and Avenue B, Christodora House offers food, shelter, health services, and educational opportunities to low-income and immigrant residents. Judd later recollects, “I think [my pay] was $100 a month. Living on $100 a month was out of this world.”

Judd participates in the Eighth National Print Annual at the Brooklyn Museum.

Judd exhibits an untitled landscape painting at a November group show at City Center Art Gallery, New York, juried by Reuben Tam, Charmion von Wiegand, and Paul Cadmus. Judd’s work is first reviewed in print: Al Newbill positively mentions him in Arts Digest, writing, “Olitsky’s Black Sea was also impressive as was Judd’s sensitively rendered river scene.”

In June, Judd exhibits a painting in a group exhibition at City Center Art Gallery. Howard Devree writes in The New York Times that Judd is among those abstract artists whose work is an example of “the growing tendency toward figurative and landscape suggestion.”

Judd exhibits abstract, landscape-based paintings in a group show, Four Americans, at the Panoras Gallery, New York. This is the first exhibition of Judd’s work at a commercial gallery. He is singled out in a review in the New York Herald Tribune: “A shining star compared to the rest, a painter of sure instinct whose heart and mind work together. Nature is used as a starting point, but undergoes a completely satisfactory transformation in the harmonics of composition and color. There is a freedom of touch which allows the natural to breathe, to let air flow. A sturdiness and shimmer in the composition and originality of design in The Bush, The Pool, The Bridge indicate the makings of a first-rate painter.”

Judd exhibits eight abstract oil paintings in Don Judd and Nathan Riesen at the Panoras Gallery. The show is reviewed positively in four publications. Comparing Judd’s work to that of Riesen, The New York Times reports, “The landscapes of Don Judd are more emphatic, rendered in schematic, flat symbols of houses, walls, trees and water. The sharp imagery that emerges from these nearly abstract paintings is the result of a firm, clear principle of simplification, which the artist sustains.”

With an eye toward teaching as a possible means of support, Judd enrolls in two courses at New York University during the fall semester: “Critical History of Art: Modern Art and Contemporary Culture” and “The Artist-Teacher in Contemporary Education.”

Judd shows work in a midseason salon at Camino Gallery, New York. More than eighty artists participate, including Milton Resnick, Ad Reinhardt, Hans Hofmann, Franz Kline, Alan Kaprow, Willem de Kooning, George Segal, Al Held, Nicholas Krushenick, Ray Johnson, and Ellsworth Kelly. Camino Gallery was one of the Tenth Street Galleries, a group of artist-run, cooperative galleries that operated in Manhattan’s East Village in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

Judd takes a part-time job as an arts and crafts teacher at the Police Athletic League (PAL) in New York. He meets John J. Jerome, a boxing instructor, who becomes a lifelong friend and his lawyer. Jerome recalls, “While at PAL, Don marveled at the work young kids turned out. One kid, little Ernie, made beautiful orange and red bursting suns. I had his big brother at the pool table. He carried a switch blade and had a zip gun. Don and I bonded over nature/nurture discussions which we never definitively resolved.”

Judd has his first solo exhibition of paintings, Don Judd, at the Panoras Gallery. Judd’s painting A Defile is accessioned by The Staten Island Institute of Arts and Sciences. This is the first Judd work acquired by a museum. A reviewer writes that Judd “brings orderly, quiet abstractions to his first one-man show. . . . It is an abstraction of the classic kind, savoring of Hélion, but in spite of this precision, a loose wondering quality, a holding back, makes it intriguing.”

In September, Judd begins a master’s program in art history at Columbia University. He initially takes courses including “The Venetian School of Painting in the Sixteenth Century,” “Ancient Mexican and Peruvian Art,” and “The Art of the Far East.” He studies with Rudolf Wittkower, whose work on proportion in Alberti’s architecture reignites Judd’s interest in architecture.

In addition to attending graduate school, Judd teaches shop class and history at the Allen-Stevenson School, a private all-boys school on Manhattan’s Upper East Side.

In the fall, Judd moves to 326 East Eighty-Fifth Street.

1959 is a pivotal year for Judd. In the studio he is developing a group of paintings that contain curving shapes that appear to push against one another and sometimes overlap. His palette changes from earth tones to reds and blues, black and white. Leaving behind references to deep space and figure and ground, Judd seems to explore the ways in which a more unified surface can be obtained.

Judd flourishes academically and begins to develop a clear, well-defined writing style. For art historian Meyer Schapiro’s seminar “Modern Painting Since 1900,” Judd submits an essay on James Brooks’s painting Ainlee. The essay provides insight into Judd’s thinking and method of analysis: “Ainlee may be analyzed as composed of discrete areas, each with a function, but the abstractions of the analytic method must be acknowledged; the most important idea of this painting is that the large areas are to remain open, are to be a result of the brushwork, are not to be seen as separate units. The structure is found in the paint, on the surface of the canvas; it and its method of execution are a unity.”

During Meyer Schapiro’s course “American Painting,” Judd later recounts, “Schapiro said that Tom Hess wanted some reviewers, if anybody would be interested. A couple of us raised our hands; I thought I might need a part-time job, so I raised mine.” Judd is hired to write for ARTnews and publishes his first piece of professional criticism: a set of “Reviews and Previews.”

Judd meets the artist Yayoi Kusama when he writes a review of her exhibition at the Brata Gallery, New York. The review, published in ARTnews, opens, “Yayoi Kusama is an original painter. The five white, very large paintings in this show are strong, advanced in concept and realized.” Judd purchases one of her Infinity Net paintings for $200, which he pays in four installments.

Judd is hired by Hilton Kramer, then the editor of Arts (later renamed Arts Magazine), to review exhibitions. He will write for Arts regularly for the next six years. Judd notes, “The first reviews for Arts Magazine appeared in December 1959 and continue, with only a few interruptions, until March 1965; there are reviews in a total of 43 issues.” In 1974, he reflects, “The job with Arts provided most of my money until the last year. I wrote criticism as a mercenary and would never have written it otherwise. . . . The few articles were a great help, especially in the summer. In the letter hiring me Kramer gives the rate at the time: ‘For a review of 300 words, the rate is six dollars; for 150 words, four dollars; for a one sentence review, three dollars.’”

Judd writes his first review of John Chamberlain’s work in the February issue of Arts. He concludes, “The unique aspect is the color. The paint is folded into the convolutions of the metal and is unquestionably integral to the work. Colored sculpture has been discussed and hesitantly attempted for some time, but not with such implications. The color here is insufficient but the possibilities are exciting and Chamberlain has a long time and the start to find them.” Judd later acquires Chamberlain’s work for permanent installation at 101 Spring Street and in Marfa.

In March, Judd writes a review of Jasper Johns’s show at Leo Castelli Gallery, New York, for Arts. Judd states that Johns is “precise, inventive, authentic, and important. . . . All of the paintings are interesting, but False Start is especially so. Stenciled names of the various colors, seldom in their own, replace the attached objects, and penetrate and shape, since the color is opposed, the clusters of hard high-keyed blue, red and orange, which, with the words, are exchangeable in the space, and so maintain the explicit, thin depth with considerable variation.”

Judd reviews Lee Bontecou’s exhibition at Leo Castelli Gallery in the December issue of Arts. He writes, “A dark void is the denouement of the many advancing and narrowing circles of canvas and metal ribs, splayed upon a rectangular iron frame, in each of these potent, explicit and unusual constructions. Bontecou displays an altogether novel authority and breadth of expression and of the means necessary to it. Qualities and elements which hitherto have been partial, such as her oppressive disturbing primitivism and desolation are now stated bluntly, completely, and with great conviction.”

Yayoi Kusama tells Judd about an available loft space in her building, 53 East Nineteenth Street. He rents the loft and establishes his studio on the fourth floor for $100 per month. Other artists live and work in the building, including David Whitney, Larry Zox, Frosty Myers, and Kusama. Judd later notes it was in this space that he began his efforts “to permanently install as much work as possible, as well as to install some by other artists.”

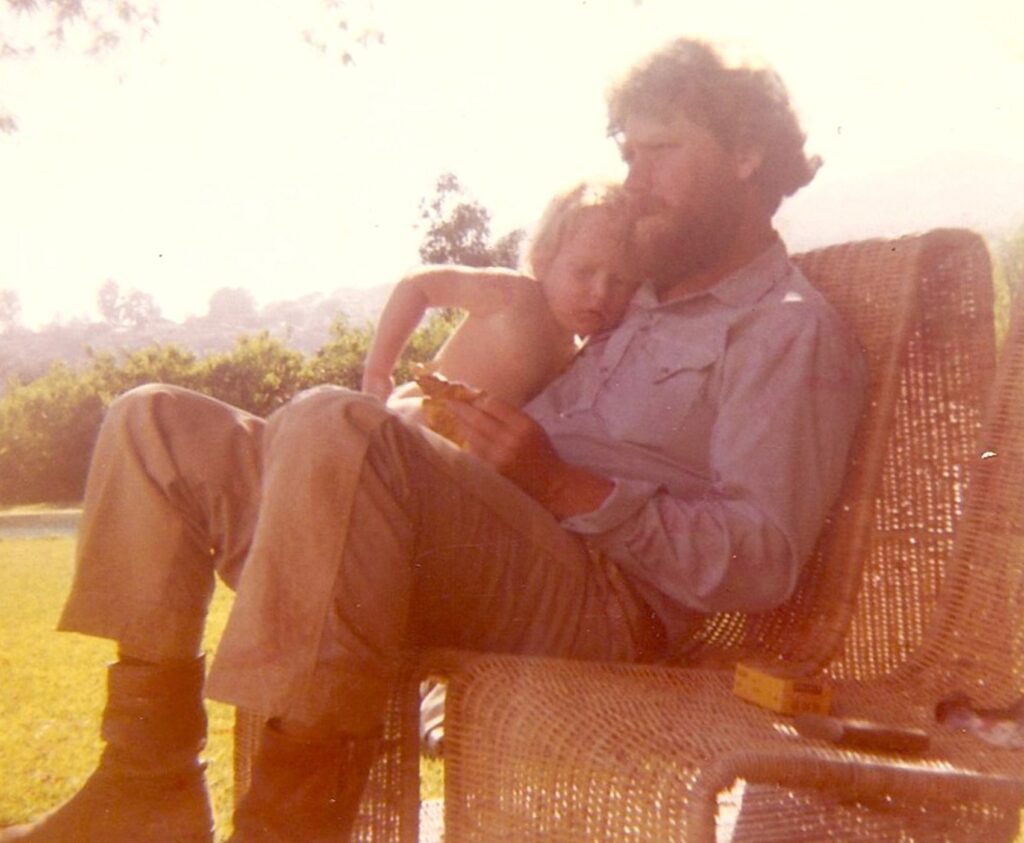

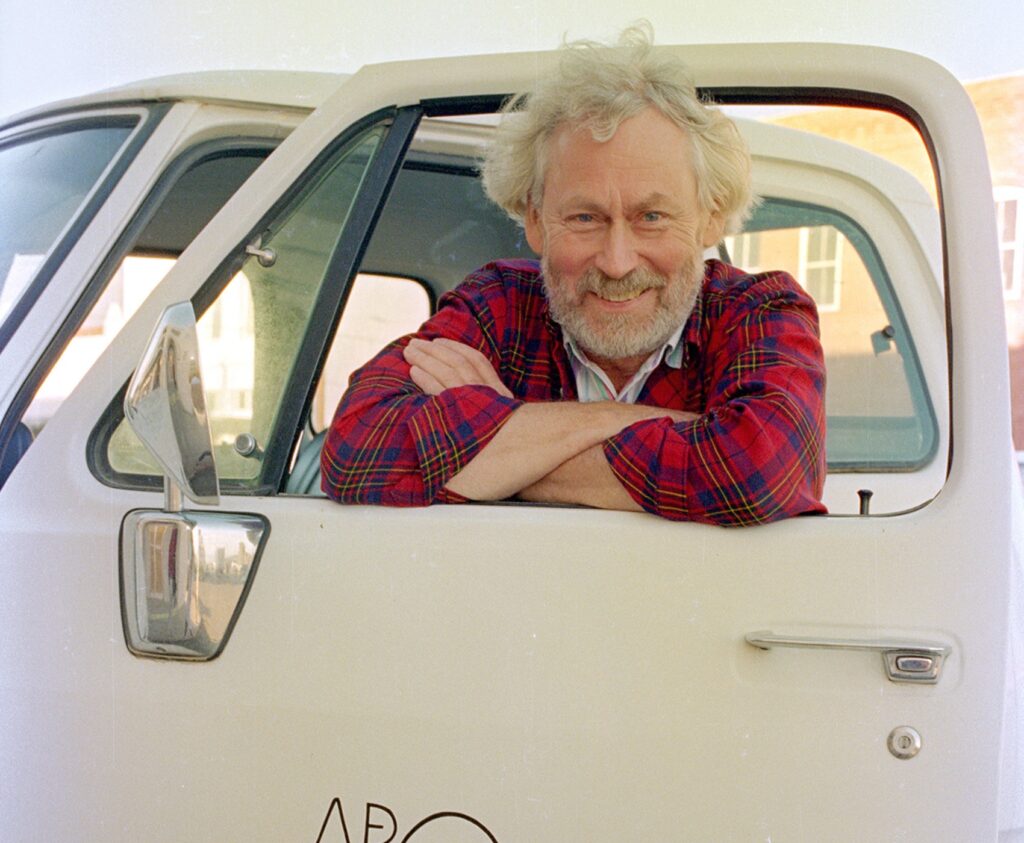

Judd works on a woodcut with his father, Roy Judd. Roy, a skilled second-generation carpenter, becomes Judd’s printmaker and fabricator of early wood works. They make Judd’s first two sets of prints: twenty-six parallelograms in cadmium red light, followed by twelve parallelograms in cerulean blue.

With the exception of foreign languages and a thesis, Judd completes course requirements for a master’s degree in art history from Columbia University. He continues writing art reviews and solidifies his studio practice. Having explored the making of abstract paintings with overlapping shapes, Judd now creates works that are larger in scale and have a more limited palette, often red and black. His earlier abstract shapes give way to simple looping lines. Soon, he begins to work on a textured surface, mixing paint, sand, and sometimes wax.

Judd makes his first low-relief painting (DSS 22), followed by the first to include a found object (DSS 23). Moving quickly toward three-dimensionality, he explains how he arrived at his third relief (DSS 25): “One of the first three-dimensional ones started off as a piece of canvas from a failed painting that I tried to turn up, but I couldn’t make the canvas turn up evenly. So after a while, it occurred to me to change the material and use something that would curve naturally. I threw out the piece of canvas and replaced it with galvanized iron. . . . I went from low to high relief and then to freestanding works.”

Judd makes his last painting using oil and wax on canvas (DSS 27).

Judd makes his first work that incorporates plastic, an elliptical yellow O (DSS 30). Roberta Smith would later reflect on this work, “The letter from a commercial sign, a large yellow plexiglass O is such a surprise. Used backwards and on its side in a painted relief, it forms an abrupt through like circle, a smooth, indented, vaguely industrial, foreign body which holds its own at the center of a rough red field, compensating in dimensionality for what it lacks in area. Still, the O also doesn’t become the center of attention, you continue to see the relief as a whole, right out of its edges.”

Richard Bellamy, founder and director of Green Gallery, New York, views Judd’s work for the first time in the spring. “I lived in a loft on Nineteenth Street and Fourth Avenue; Kusama, who lived below me there, helped me find the place,” Judd later recalls. “Bellamy came to see her work, and she brought him upstairs.”

Judd reviews an exhibition of Stuart Davis’s paintings at Downtown Gallery, New York. The review is published in the September issue of Arts Magazine. “There should be applause. Davis, at sixty-seven, is still a hot shot. . . . His painting, certainly not by coincidence, gained in scale, clarity and power after 1945, and gained further after 1950.” Judd later installs Davis’s Detail Study for Cliché on the fifth floor at 101 Spring Street.

In the fall, Judd begins teaching art at the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences, a position he will continue through spring 1964.

In the winter, Judd meets Dan Flavin at a gathering in a Brooklyn apartment organized to discuss the possibility of a cooperative artist-run gallery. Shortly thereafter, Judd is introduced to the painter John “Jack” Wesley through a mutual friend, the artist Mario Yrizarry. Judd, Flavin, and Wesley become lifelong friends. Judd later installs both Flavin’s and Wesley’s work in his spaces.

Judd creates his first freestanding work in three dimensions (DSS 32). Comparing it to the reliefs, Judd writes, “I didn’t want it to sit back against the wall. A piece that was completely three-dimensional was a big event for me.” This work is shown at the faculty exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum Art School. “The next three-dimensional piece is a right-angled floor piece with a bent pipe (DSS 33). It’s a regular three-dimensional piece. . . . This one really works; it’s very definitely four-sided and opened up.” In his 1993 essay “Some Aspects of Color in General and Red and Black in Particular,” Judd reflects on the significance of this trajectory: “The new work seemed to be the beginning of my own freedom, with possibilities for a lifetime. The possibilities and the lifetime are now well along.”

In a group show at Green Gallery, Judd’s first exhibition with the gallery, he shows two reliefs (DSS 28 and DSS 34) and a floor piece (DSS 33). Other artists in the show include Dan Flavin, Larry Poons, Milet Andrejevic, Yayoi Kusama, Robert Morris, Lucas Samaras, and George Segal. Sidney Tillim writes in Arts Magazine that Judd’s relief is “the most sensible, most rigorous item in the show. . . . The work’s claim on space is real.”

In the January issue of Arts Magazine, Judd reviews Lee Bontecou’s work at Leo Castelli Gallery, writing, “Bontecou is one of the best artists working anywhere. . . . The best American art is, in diverse ways, skeptical. Bontecou makes her work so strong and material that it only asserts itself. Its quality is too intense to be extended into solipsistic generalizations. The work has a primitive, oppressive, and unmitigated individuality. It is credible and awesome.”

Judd writes his first review of John Wesley’s paintings for Arts Magazine: “Wesley’s paintings, if they are pop art, are retroactive pop. . . . The forms selected, the shapes to which they are unobtrusively altered, the order used and the small details are humorous and goofy. This becomes a cool, psychological oddness.”

In May, Judd shows one work in his second group show at Green Gallery in company with Robert Morris, Larry Poons, Kenneth Noland, Tadaaki Kuwayama, Frank Stella, and Darby Bannard.

Judd meets Margaret Julie Hughan Finch, who is working as a gallery assistant at the Jacques Seligman Gallery. Judd invites Finch, “Would you like to come to a chicken farm in New Jersey? We’re going to watch Yvonne Rainer dance on a chicken coop roof.” The performance Improvisation on a Chicken Coop Roof, by Rainer and Trisha Brown, takes place on May 19 at Yam Festival on George Segal’s farm in North Brunswick. Yvonne Rainer is a leading figure in the Judson Dance Theater, a collective of experimental choreographers, visual artists, composers, and filmmakers, founded with Brown and others.

Judd and Finch begin a relationship. While apart, they write regularly. In October, Judd writes of his discovery of a decent metalworking shop, located around the corner, and sketches his works in progress for his upcoming solo show at Green Gallery.

In November, the first group of parallelogram wood-blocks are made by Roy Judd. Initially there are thirteen pairs of unique configurations, each a mirror image of its counterpart and painted in cadmium red light. The numbering system used to identify these blocks is not chronological but rather based on the configuration of each block and indicates left- or right-facing orientation. These are the first of many groups of parallelogram wood-block objects based on twenty-seven configurations that will be made by Judd throughout his lifetime.

Judd has his first Green Gallery solo exhibition, Don Judd (December 17, 1963–January 11, 1964). All works are made by Judd with his father. The exhibition includes four wall reliefs (DSS 40, DSS 42, DSS 43, and DSS 44) and five objects placed directly on the floor (DSS 35, DSS 37, DSS 38, DSS 39, and DSS 41). In addition, there are three parallelogram wood-blocks, the objects from which the early woodblock prints are pulled (DSS 331, DSS 333, and DSS 347). Each wood-block is considered unique. While reviews are generally negative, Michael Fried writes a positive review in Art International, calling it an “assured, intelligent show . . . one of the best on view in New York this month.”

Image: Installation view, Don Judd, Green Gallery, New York, December 17, 1963–January 11, 1964. Photo courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery.

Judd helps Kusama with her first environmental installation, Aggregation: One Thousand Boats Show, at Gertrude Stein Gallery, New York. Judd recalls, “I remember I helped her stuff the phallic things; it was days on end of stuffing. I had a lot to do with it. I helped get the rowboat through the streets originally. We pushed the rowboat through the streets on dollies.”

On February 15, art historian Bruce Glaser records an interview with Judd, Frank Stella, and Dan Flavin, broadcast as “New Nihilism or New Art?” on WBAI-FM, New York. Judd states, “I’m totally uninterested in European art and I think it’s over with.”

For Arts Magazine, Judd reviews the exhibition Black, White and Gray, organized by curator Sam Wagstaff Jr. at the Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, Connecticut. The show is considered to be the first to introduce “minimalist” work to the public. Judd singles out the work of Stella and writes about Flavin’s work for the first time, noting that “Dan Flavin’s fluorescent light and Frank Stella’s black painting and aluminum one have some connection to the exhibition’s flat and unhierarchical view of things. The work of both is more complex. Although they exclude painterly art, their work is decidedly art and is visible art.” He also writes, “Things that exist exist, and everything is on their side. They’re here, which is pretty puzzling. Nothing can be said of things that don’t exist. Things exist in the same way if that is all that is considered – which may be because we feel that or because that is what the word means or both. Everything is equal, just existing, and the values and interests they have are only adventitious.”

On March 14, Judd and Finch wed in a private ceremony in a Manhattan apartment belonging to Finch’s paternal grandmother. They are joined by a small group of family members and close friends, including John Jerome, Nathan Riesen, and Dan Flavin.

On March 30, Judd places an order with Bernstein Brothers Sheet Metal Specialties to cover a wooden wall piece with a semicircular trough in the top plane with a sheet of galvanized iron (DSS 47). This work is the first fabricated by the New York shop, which Judd will work with for the rest of his life. Judd later credits one metal worker in particular: “The work is done by one man, José Otero. He knows how to make them well, how I originally wanted them, and they continue to get done in that way, and that all depends on José Otero. It’s just this one guy, and that’s kind of lucky.”

Judd participates in the exhibition Eleven Artists, organized by Dan Flavin at the Kaymar Gallery, New York. The group show also includes works by Jo Baer, Darby Bannard, Dan Flavin, Irwin Fleminger, Ward Jackson, Sol LeWitt, Larry Poons, Robert Ryman, Frank Stella, and Leo Valledor.

In his third group exhibition at Green Gallery, Judd shows alongside Dan Flavin, Larry Poons, Richard Smith, Neil Williams, and George Segal. Judd concurrently shows work at Bird S. Coler Hospital Grounds, Manhattan State Hospital, Ward’s Island Park, New York.

On November 9, Barnett and Annalee Newman host Judd and Finch for dinner. The Newmans will become their close friends. Soon after, Judd writes about Newman’s work for the first time, for Das Kunstwerk, although it is not published: “[His] paintings are some of the best done in the United States in the last fifteen years. . . . It’s important that Newman’s paintings are large, but it’s even more important that they are large scaled. . . . This scale is one the most important developments in twentieth-century art. Pollock seems to have been involved in the problem of this scale first.” The essay “Barnett Newman” is eventually published by Studio International in 1970.

In December, Judd publishes an essay for the first time. In “Local History,” in Arts Yearbook 7, he observes that one should report history faithfully: “The history of art and art’s condition at any time are pretty messy. They should stay that way. One can think about them as much as one likes, but they won’t become neater; neatness isn’t even a very good reason for thinking about them.”

1964 Exhibition Summary

By the end of 1963, Judd has produced a major edition of prints using wood-blocks made by his father, Roy Judd, and established what will become a lifelong working relationship with sheet-metal fabricator Bernstein Brothers. After his 1963–1964 Green Gallery solo show, he emerges as an artist/critic producing provocative, groundbreaking work that is neither sculpture nor painting. The next few years will see Judd develop as an exceptional artist with a growing international reputation; the number of gallery and museum exhibitions featuring his work increases at an exponential rate.

“Interview with Lucy R. Lippard and William C. Agee,” in Donald Judd Interviews, 225.

“Interview with Lucy R. Lippard and William C. Agee,” in Donald Judd Interviews, 225.

Al Newbill, “City Center Group,” Arts Digest, November 15, 1954, 29.

Howard Devree, “About Art and Artists: Loan Exhibition of 160 Paintings Opens Today at the Modern Museum,” The New York Times, May 31, 1955, 27.

C.B., New York Herald Tribune, October 22, 1955.

D.A., “About Art and Artists: Scope of Contemporary Printmaking Is Indicated in Three Current Shows,” The New York Times, September 18, 1956, 27.

John Jerome, email to Ellie Meyer, December 28, 2018.

Edith Burkhardt, “Don Judd,” Artnews, Summer 1957, 77.

Judd, “James Brooks: Ainlee” (1959), in Donald Judd Writings, 42–43.

“Interview with Lucy R. Lippard and William C. Agee,” in Donald Judd Interviews, 256.

Judd, “Reviews and Previews: New Names This Month” (September 1959), in Donald Judd: Complete Writings 1959–1975 (1975; repr., New York: Judd Foundation, 2015), 2.

Smith, “Donald Judd,” in Donald Judd: Catalogue Raisonné of Paintings, Objects, and Wood-Blocks 1960–1974, 10.

Judd, introduction, Donald Judd: Complete Writings 1959–1975, vii.

Judd, “In the Galleries” (February 1960), in Donald Judd: Complete Writings 1959–1975, 10.

Judd, “In the Galleries” (March 1960), in Donald Judd: Complete Writings 1959–1975, 14.

Judd, “In the Galleries” (December 1960), in Donald Judd: Complete Writings 1959–1975, 27.

Judd, “On Installation” (1982), in Donald Judd Writings, 309.

“‘Don Judd: An Interview with John Coplans’ from the exhibition catalogue Don Judd” (1971), in Donald Judd Interviews, 341.

Roberta Smith, “Donald Judd: Perceptual Conceptual,” The Village Voice, December 6, 1983, 89.

“Interview with Phyllis Tuchman” (June 4, 1976), in Donald Judd Interviews, 496.

Donald Judd, “In the Galleries” (September 1962), in Donald Judd: Complete Writings 1959–1975, 55.

“‘Don Judd: An Interview with John Coplans,’” in Donald Judd Interviews, 341.

Judd, “Some Aspects of Color in General and Red and Black in Particular” (1993), in Donald Judd Writings, 852.

Sidney Tillim, Arts Magazine, March 1963, 62.

Judd, “In the Galleries” (January 1963), in Donald Judd: Complete Writings 1959–1975, 65.

Judd, “In the Galleries” (April 1963), in Donald Judd: Complete Writings 1959–1975, 82.

Interview with Julie Finch, September 8, 2006. Judd Foundation Oral History Project, Judd Foundation Archives, Marfa, Texas.

Michael Fried, “New York Letter,” Art International, February 15, 1964, 26.

“Interview with Alexandra Munroe and Reiko Tomii” (December 8, 1988), in Donald Judd Interviews, 633.

“‘New Nihilism or New Art?,’ radio program with Bruce Glaser (moderator), Dan Flavin, and Frank Stella” (February 15, 1964), in Donald Judd Interviews, 53.

Judd, “Nationwide Reports: Hartford” (March 1964), in Donald Judd: Complete Writings 1959–1975, 119.

Judd, “Nationwide Reports,” in Donald Judd: Complete Writings 1959–1975, 117.

“Interview with Paul Cabon” (Spring 1987), in Donald Judd Interviews, 604.

Judd, “Barnett Newman” (1964), in Donald Judd Writings, 153.

Judd, “Local History” (1964), in Donald Judd Writings, 25.